‘Critical’: Disease 70,000 Australians don’t know they’ve got

Tens of thousands of Australians are living with a preventable but potentially life-threatening disease – and many don’t even know it.

As many as 70,000 Australians are living with a preventable but potentially life-threatening disease – and many don’t even know it.

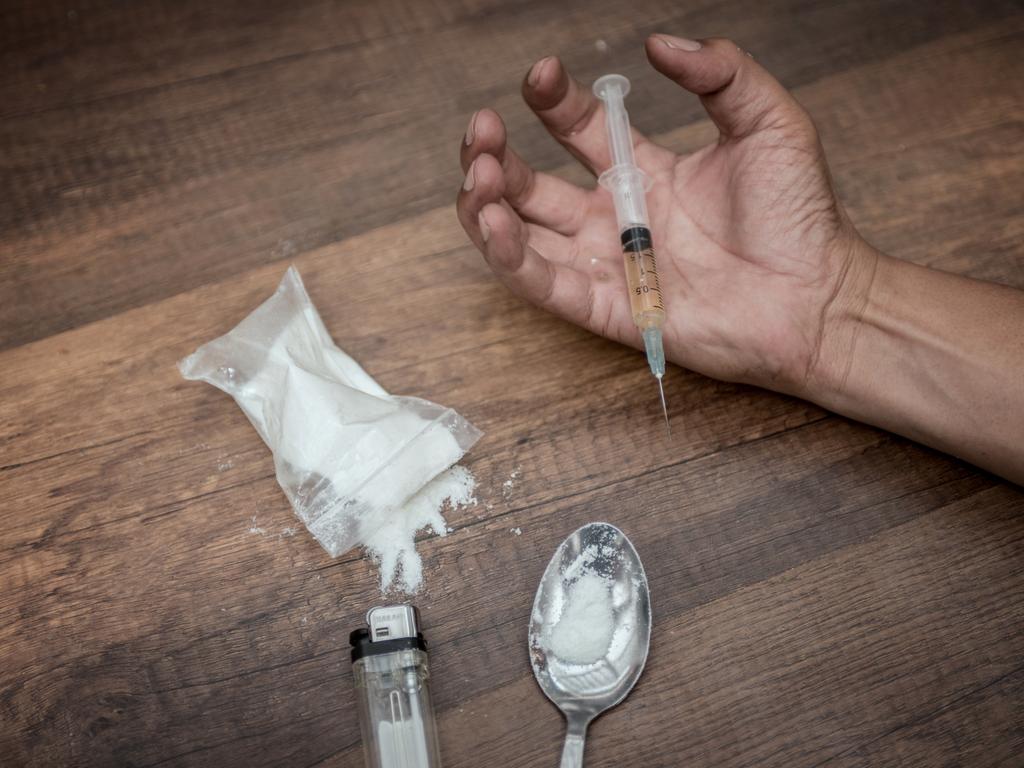

Hepatitis C is a bloodborne virus that primarily attacks the liver and, if untreated, can lead to cirrhosis (scar damage), organ failure and cancer. The illness is spread through blood-to-blood contact – most commonly by sharing injecting equipment.

The introduction of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) as a cure with 97 per cent efficacy was a “game changer” in 2016, one that prompted Australia to announce its intention to become one of the first countries in the world to eliminate hepatitis C by 2030.

While roughly 100,000 people have now been cured, experts warn our goal of eradicating the disease in the next six years is under threat, with the number of people coming forward to seek treatment having fallen significantly in recent years.

Speaking to the ABC’s 7.30 program on Wednesday, the Burnet Institute’s Professor Margaret Hellard said Australia is “at a critical juncture” in terms of combating the virus.

As the rate of new infections rises – in 2023, 13,222 new cases were detected – the number of people being treated with DAAs has dropped annually, from a peak of 33,202 people in 2016 to just 5426 last year. Of the 70,000 people predicted to have hepatitis C, the Indigenous population is disproportionately affected, with an estimated 20,000 cases.

“If treatment uptake doesn’t increase, we’re going to struggle to meet our elimination targets,” Professor Hellard warned.

“We know we need to get enough people treated so that there’s hardly anybody left with hepatitis C, and that means the number of new infections falls because you don’t get transmission.”

The stigma associated with injecting drugs – which is widely disapproved of and illegal in most parts of the country – means people with hepatitis C are likely to experience “persistent discrimination”, acting as a barrier to seeking treatment, a group of academics from La Trobe University explained in a piece for The Conversation in December.

“Such discrimination happens most commonly in health care, when doctors, nurses and other healthcare professionals become aware of someone’s hepatitis C status,” they wrote.

“This can include withholding treatment, diagnostic overshadowing (when workers attribute physical symptoms of illness to mental health issues), rude or unwelcoming behaviour, and excessive infection control like double-gloving.

“This may lead some people to avoid seeking medical care entirely.”

High rates of the disease in prisons is another key reason why it’s not being eliminated.

Australian prisons do not have needle and syringe exchange programs – a “glaring omission”, the La Trobe University team said, that fails to ensure drug users have access to sterile equipment, thus increasing transmission.

It also puts those inmates who have been cured of hepatitis C at risk of reinfection.

“I understand that in prisons, you could have an argument about, ‘What are drugs doing in prisons?’” Prof Hellard told 7.30.

More Coverage

“But we know that drugs are in prison. We know that injecting occurs in prisons, so why not provide appropriate harm reduction and care for people?”

It is “increasingly clear”, the La Trobe University academics said, that as well as access to sterile injecting equipment in prisons, Australia needs to “direct resources to what happens ‘post-cure’, assuring people that stigma-free health care is available to them”.

“We also need to tackle the laws, policies and practices that allow stigma and discrimination to linger in people’s lives.”