Coronavirus: How Singapore, South Korea, Hong Kong and Taiwan are beating killer virus

As the world shuts down because of the deadly coronavirus, some countries seem better off than others. Here’s why.

The world is shutting down. COVID-19 has bypassed all efforts to contain it. But some nations seem better off than others. Why?

The numbers are staggering. The ill. The dead. Coronavirus has hit the exponential growth curve across the world.

But, amid the confusion, clear trends are emerging.

Some countries appear to be holding back the virus.

South Korea suffered an explosive outbreak in early February, mainly through a secretive Christian sect. But aggressive tracking of social contacts and targeted lockdowns have so far succeeded in slowing the virus’ spread.

It’s a similar story in Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan.

They have one thing in common: They were scared into action by their experience with the 2003 SARS outbreak.

This time, they were prepared. They had plans.

So, what works?

OUTFLANKING MANOEUVRES

“With the number of cases around the world increasing rapidly and countries taking different measures, there is considerable concern and debate about if and when to start more drastic social or physical distancing measures,” says professor of epidemiology Tony Blakely.

“Should we close schools and workplaces? And should this happen now? My analysis and modelling of the situation suggests this is unlikely to be our best strategy – just yet.”

Countries that are “successfully” flattening the curve moved quickly to impose travel restrictions and apply social distancing measures to their communities.

But that doesn’t always mean the closure of schools. While Hong Kong has cancelled classes, Singapore has not. South Korea still has its open but has introduced strict social distancing measures.

None have adopted the iron-fisted approach of China. It put tens of millions of its citizens into enforced lockdown. Nobody was allowed to leave their homes in entire cities and provinces.

Epidemiologists striving to identify the most effective – and least dramatic – means of slowing COVID-19 have been studying these states carefully.

Most agree that vigorous contact tracing and pre-emptive isolation has proven effective. But it’s now too late for this tactic to be applied elsewhere. The pandemic is simply too big.

Instead, the emphasis is again falling back on social distancing and lockdowns – particularly when and how they are applied.

“If our endgame is to flatten the curve, a steadily increasing amount of social distancing over the coming weeks is the best way to go,” Prof Blakely says.

SOUTH KOREA

Seoul had a crisis on its hands. A Christian sect had unwittingly spread the virus throughout the country. And its culture of secrecy made it hard to trace the paths of hundreds of carriers. In late February, it recorded a surge of more than 900 cases in one day. Daily COVID-19 cases fell to below 100 last week but have since begun to rise again.

Seoul “flattened” the epidemiological curve. But it has not been able to defeat the virus entirely now it is established in its population.

“Testing is central because that leads to early detection,” Foreign Minister Kang Kuyng-what said. “It minimises further spread, and it quickly treats those found with the virus.”

Work-from-home measures have also been implemented. Large gatherings have been shut down.

RELATED: Follow the latest coronavirus updates

RELATED: Extraordinary virus restrictions imposed

Seoul quickly introduced drive-through test centres for convenience and reduced risk to health workers.

It issued masks to students and put up screens to enforce social distancing in schools.

All international travellers have been tracked for several weeks. They are also required to self-report their health and location via a government-supplied app.

But a recent uptick in South Korea’s diagnosed cases indicates rigorous testing and contact tracing is losing its effectiveness. There are simply too many sick. With more than 7000 confirmed cases, health workers just don’t have the time or resources to catch them all.

HONG KONG

Hong Kong has had plenty of experience with epidemics. SARS was a real shock to the densely populated city-state. And that was closely followed by the H1N1 flu pandemic.

So its people, and its government, have learnt to take health measures seriously.

As soon as news broke of a strange new virus in China, Hong Kong alerted its doctors. From the first week of January, it was carefully monitoring any visitor from Wuhan. Soon, all its border crossings to the mainland were closed.

RELATED: What is social distancing?

RELATED: What social gatherings are now banned?

The education system was shut down on January 23. Social distancing was encouraged, and businesses instructed to get their employees working from home as soon as possible.

Hong Kong took strong measures early. But health experts have noted its population is starting to show signs of “fatigue”. After months of voluntary isolation, they’re beginning to let their guard down. They’re heading back out into the streets, to the gym, to restaurants and cafes.

Cabin fever is taking its toll. And that threatens to revive the virus’ spread.

SINGAPORE

The island-city’s authoritarian government took strict measures, early. Like Hong Kong, it quickly barred visitors from Wuhan. All visitors from any nation known to have COVID-19 cases were required to go into 14 days quarantine. Like South Korea, the movements and contacts of every case have been traced. Everyone suspected of being exposed is being ordered into quarantine.

All large gatherings have been banned. But schools remain open.

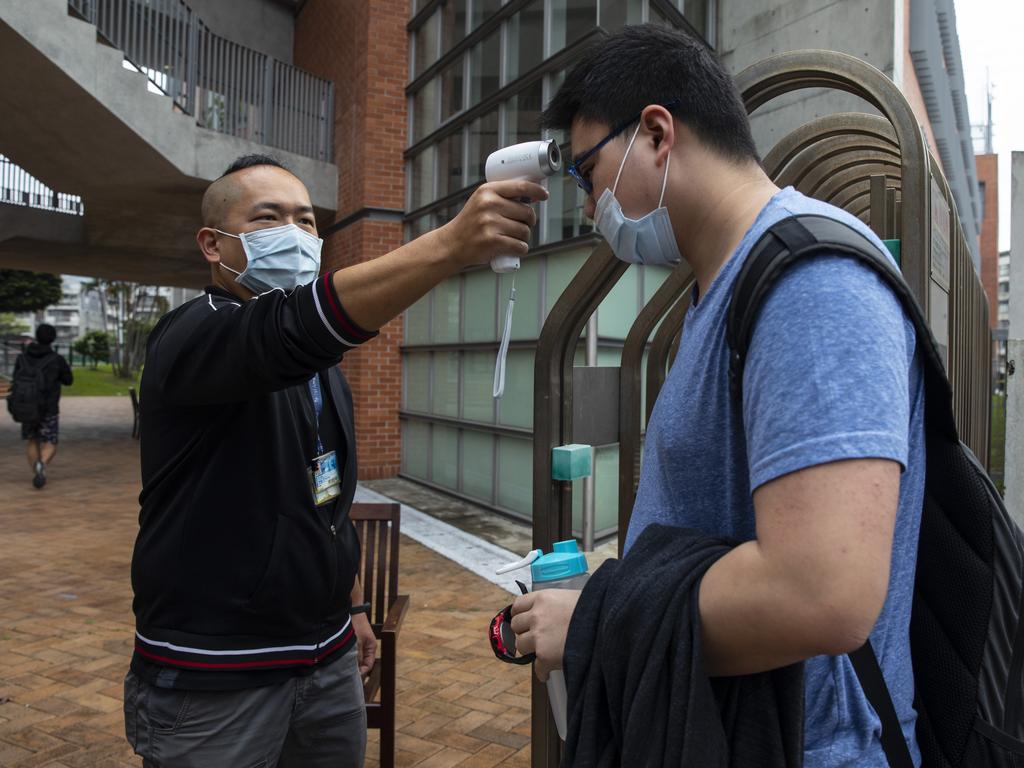

All students are required to take a temperature test every day before they are allowed to enter. Every class is photographed. That way, if a student later becomes ill, authorities know who may have been exposed during COVID-19’s infectious, non-symptomatic stage.

RELATED: Should you stop taking public transport?

RELATED: Blood types more at risk of infection

Singapore’s health workers also immediately set about studying the sick. It quickly developed new testing techniques. And the apartments occupied by several patients were analysed to determine the risk of the virus spreading through a building.

TAIWAN

Taipei has taken a less dramatic approach to contain the virus. But it also quickly initiated a mass testing and contact-tracing program.

Large gatherings have not been banned. Instead, they are actively discouraged.

Taipei also moved quickly to seize control of its supply of medical masks. These are now price controlled and rationed.

And while the voluntary social-distancing policy appears to have worked well in slowing COVID-19’s spread through Taiwan, anyone found breaching quarantine orders faces a fine of more than $50,000.

RELATED: Should pregnant women self isolate?

RELATED: What are the coronavirus symptoms?

AUSTRALIA

Prof Blakely has modelled several different epidemic policy scenarios and their possible results in Australia. He assumes the number of COVID-19 cases here has been doubling every four days since mid-March. Each scenario estimates the effectiveness of different measures in bringing that transmission rate down.

First is a do-nothing approach:

“The result is unpleasant – disastrous even,” he says. “New infections per day in Australia would peak at over 500,000 (and from estimates deduced from Imperial College model parameters, a third of which would be symptomatic), absolutely swamping health services.”

Second is the staged rollout of new social distancing measures:

“There are an infinite number of options of when and by how much to relax social distancing,” Prof Blakely says. “In (my) scenario, the daily new infections peak at about 125,000 in late May, with the peak of symptomatic cases lagged up to a week – still not pleasant, but considerably better.”

Third is a rapid application of social isolation policies:

“This scenario pushes the peak of the epidemic to June but does not significantly reduce the daily load of new cases compared to the previous model,” Prof Blakely says.

Finally, he modelled a China-like draconian crackdown – ordering everyone to stay indoors:

“This approach reduces the peak number of new infections per day to about 100,000, which the model predicts will happen in mid-to-late June,” Prof Blakely says.

While strict isolation measures may seem appealing on the surface, Prof Blakely says there is more to the story. “The downside – and this is important – is that social distancing policies (with all their economic consequences and social disruption) will have to be in place for longer to achieve the same total number of cases at year’s end.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel