Coronavirus Australia: ‘Long tail’ of COVID-19 may mean we have to live with virus for months

While Australians are becoming increasingly keen to relax virus restrictions, the stats show we will be stuck with the pandemic for a long while yet.

Yesterday in Australia just 21 new infections of coronavirus were recorded — and not a single case in South Australia.

Contrast that number to March 22 when 537 people tested positive to COVID-19. Or to the United States on Saturday when almost 10,000 new infections were confirmed.

Australia’s figures undoubtedly put us in the top league of nations combating coronavirus, alongside others such as New Zealand, Taiwan and South Korea.

Indeed, on Friday, deputy chief medical officer Professor Paul Kelly said Australia was on the “cusp” of slowing the disease to such an extent it could eventually “die out” here.

But those hoping for a quick end to the crisis may be disappointed. While numbers of new infections have dropped dramatically, the virus may prove difficult to stub out completely. Far from getting to zero infections nationwide within weeks, it’s very possible a small number of new cases – and possible deaths – could linger on in Australia for some time despite our best efforts.

The difficulty in shaking off COVID-19 may mean getting used to some of the current social distancing measures for months to come.

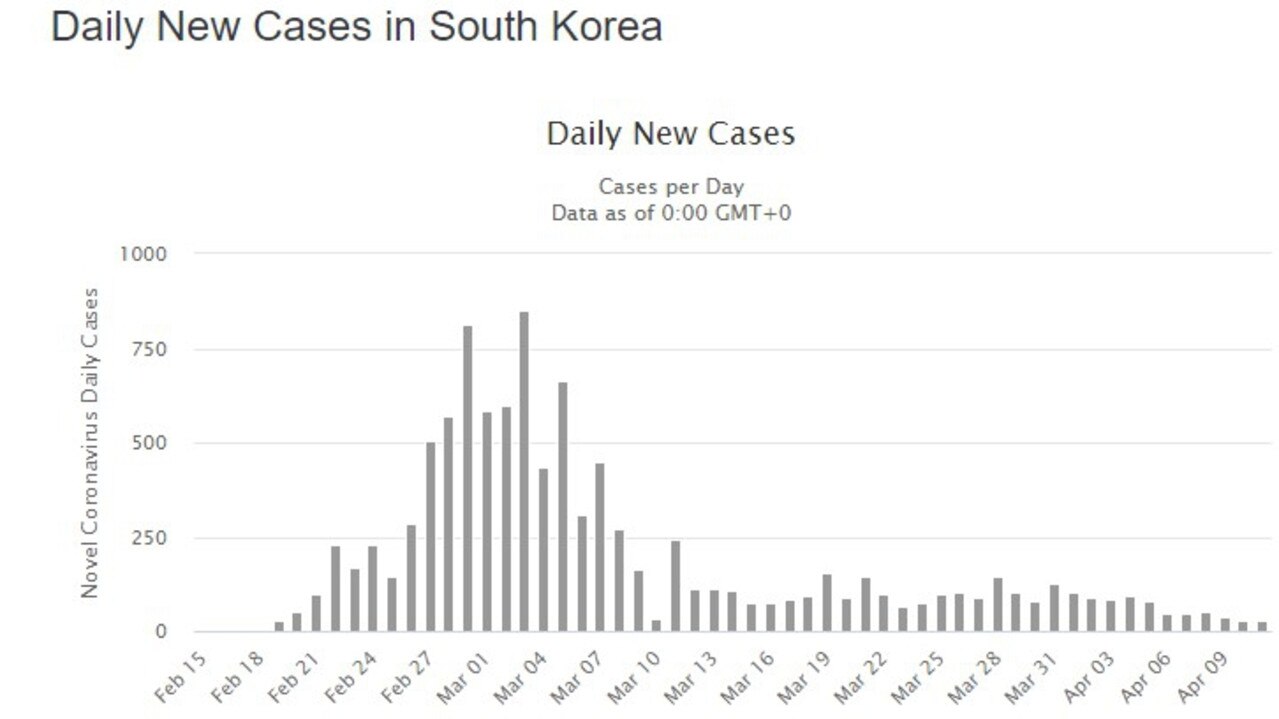

You only have to look to South Korea, which is widely credited with having the best strategy anywhere in the world for dealing with COVID-19, to see how it is struggling to rid the virus from the nation.

RELATED: Warning of 'second wave' of infections in winter

RELATED: Key to getting out of lockdown revealed

WHAT OUR NUMBERS SHOW

Australia’s infection data shows the rate of daily new cases started to drop after March 28 when there were 419 new infections, the second highest 24-hour-total of the outbreak.

By April 4, a week later, there were 176 new infections. A few days later new cases were below 100.

However, last week the number of new infections, while still trending downwards, has been far steadier. Between Monday and Thursday, daily cases bounced around between a high of 110 and a low of 96.

Cases then dropped over the Easter holiday to 21 yesterday. But New South Wales Health Minister Brad Hazzard said there was a big drop in testing over Easter as well. The state usually conducts around 3500 COVID-19 tests a day but on Saturday had done just 833.

"I don't think we can get too excited about that result at this stage,” Mr Hazzard said.

The large reduction in new cases in late March came several weeks after arrivals from badly affected countries were banned from entry. And about 10 days after the borders were closed to non-citizens, with returning Australians forced to quarantine. So, these measures appear to have had a big effect.

Indeed, two thirds of coronavirus cases in Australia have come from people getting off international flights and cruise ships.

VIRUS’ ‘LONG TAIL’

Late last month, UNSW professor and infection control expert Mary-Louise McLaws cautioned against being too optimistic about a slowdown in new cases.

“Don’t get too excited about what would appear to be a trending down,” she told the SMH.

It’s very possible Australia could now be experiencing what has happened in South Korea.

Prof McLaws said even with huge amounts of testing, treating and quarantining cases, COVID-19 has proven tough to shake off in South Korea.

“Korea has this long tail that is about 40 to 50 cases per day, and that’s been going on for about a month now and they’re doing well,” she told The Australian.

In South Korea, cases began to slow dramatically in early March as the country’s various measures, many of which Australia has now taken on, kicked in.

Nonetheless, new infections have risen continually since then albeit on a gentler trajectory, which is the envy of many other countries. Since the beginning of April, around 600 new cases have been recorded. Six people per day are now dying from COVD-19, similar to Australia’s numbers.

“Korea is a prime example of how difficult it is to remove cases from the community,” Prof McLaws said.

LOCAL TRANSMISSION

This “long tail” is likely due to local transmission. In contrast to overseas arrivals, who can be quarantined and tracked, local transmission is far more complex.

It’s where the virus passes between people with no known connection to a high-risk person.

Initially, new Australian cases were overwhelmingly from overseas. But as fewer people return, local cases have become the majority. Although, these numbers too are falling.

Keeping a lid on those cases is like playing whack-a-mole with coronavirus. Officials can try to track everyone at risk, but it could pop up somewhere else.

The worry with local transmission is that if you let it get out of control, if people unknowingly start spreading it to their friends and it begins to jump between healthcare workers, it can easily get out of control.

It’s one of the reasons health officials are keen to keep social distancing measures in place until they are sure the virus can be managed.

When Prof Kelly’s said Australia was on the “cusp” of eradicating the virus, he put several caveats on that theoretical event happening. It wasn’t a given.

A key factor is whether the infection rate can reduce to such a point where each person with coronavirus is, on average, passing it onto less than one other person.

“Once you get to that point, the virus dies out or the epidemic dies out. And so, at the moment, we're probably on the cusp of that in Australia,” he said.

"Now whether that's where we're going to be in several weeks or months’ time remains to be seen.”

It’s a warning that was reiterated today by chief medical officer Brendan Murphy who said despite the low number of new infections it was too early to know whether Australia had passed the peak of coronavirus cases.

“At the moment our position looks promising, but it is far too early to tell. This virus, as we have seen just in north Tasmania, is able to spread very, very quickly. It's very infectious,” he said.

In northern Tasmania, two hospitals have been temporarily closed with 1000 people going into quarantine to prevent an outbreak.

Prof Murphy said complacency was a key concern – that fewer new cases might lead to people ignoring government guidelines that could then send the numbers soaring again.

And that could turn the long tail back into a spike.