Drug-resistant ‘superbugs’ spreading, making diseases untreatable

A WORLD where common infections and minor injuries can kill is “far from being an apocalyptic fantasy”. Health authorities warn it’s a very real possibility.

THE rise of the superbug is now so serious that it “threatens the achievements of modern medicine”.

Sound far fetched? Well that’s how the World Health Organisation decided to begin its report about antibiotic resistance in an increasing number of diseases and infections.

The United Nations health agency goes on to say that a future world in which common infections and minor injuries can kill is “far from being an apocalyptic fantasy”.

“(It) is instead a very real possibility for the 21st century,” WHO’s assistant director-general for health security Dr Keiji Fukuda warns in the report’s foreword.

So how scared should we be?

The WHO report has put forward a “clear case” that resistance to common bacteria has reached alarming levels in many parts of the world.

“Many of the available treatment options for common infections in some settings are becoming ineffective,” Dr Fukuda says.

These common infections include pneumonia, sepsis, gonorrhoea, urinary tract infections, diarrhoea as well as other diseases like HIV and malaria.

Although it would still be unlikely for someone to die of diarrhoea in the “post-antibiotic era”, this could become more common for those unlucky enough to have antibiotic resistant germs spread to their blood stream.

Adelaide Professor John Turnidge said it could also make the spread of diarrhoea more common because antibiotics are currently used to help contain it to one person.

Prof Turnidge is an expert in specialist microbiology and infectious diseases at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital in Adelaide, and said that Australia was already struggling with treatment-resistant diseases including golden staph and gonorrhoea.

One of the standard treatments for gonorrhoea, which can generally be cured, has started to fail in a small percentage of patients.

“Which is scary because once drug resistance starts it can spread pretty quickly,” Prof Turnidge said. “We will have to get very creative for the next line of drugs.”

Some E.coli, which can cause conditions such as urinary tract infections, has also become resistant to antibiotics and could ultimately turn safe operations such as appendicitis, into dangerous procedures.

Prof Turnidge said there was no question that health professionals were worried about the situation but have now introduced a system to track the resistance of diseases, which antibiotics were being used, and in what quantities.

“Our job is to contain resistance, there will never be no resistance but our job is to keep it as low as possible,” Prof Turnidge said.

He has also recommended that patients tackle resistance by using antibiotics only when prescribed by a doctor and never sharing antibiotics with others or using leftover prescriptions.

In the World Health Organisation’s report it says the rise of superbugs has been stoked by the misuse of antibiotics and poor hospital hygiene. It described the problem as a global emergency.

“Without urgent, coordinated action by many stakeholders, the world is headed for a post-antibiotic era, in which common infections and minor injuries which have been treatable for decades can once again kill,” Dr Fukuda said.

“Unless we take significant actions to improve efforts to prevent infections and also change how we produce, prescribe and use antibiotics, the world will lose more and more of these global public health goods and the implications will be devastating,” he said.

The unprecedented report gathered data from 114 countries and focused on seven different bacteria responsible for diseases such as diarrhoea, pneumonia, urinary tract infections and gonorrhoea.

RELATED: Science has found the answer to what happens when antibiotics fail

Even so-called “last resort” antibiotics are losing their ability to fight such bacteria, with half of the patients showing resistance in some countries, the report said.

“The capacity to treat serious infections is really becoming less in all parts of the world,” Fukuda said, stressing that “antimicrobial resistance is not just a future issue ... but very much an issue today.”

Medical charity Médecins Sans Frontières said the scale of the crisis was frighteningly clear on the ground.

“We see horrendous rates of antibiotic resistance wherever we look in our field operations,” said Jennifer Cohn, an MSF medical director.

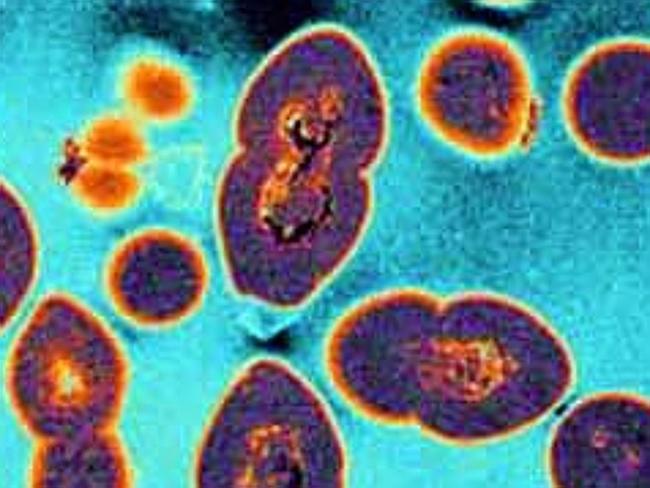

Among the report’s key findings were the global spread of resistance to carbapenem antibiotics, the last resort treatment for life-threatening infections caused by the common intestinal bacteria Klebsiella pneumonias.

Known as K. pneumonias, it is a major cause of hospital-acquired infections such as pneumonia and sepsis, often hitting newborns and intensive-care patients.

Resistance to one of the most widely used antibacterial medicines for the treatment of urinary tract infections caused by E. coli — fluoroquinolones — is also widespread.

There was hardly any resistance when the drugs were introduced in the 1980s, but it now affects half of patients in many part of the world, the WHO said.

The problem is a particular concern in Africa, the Americas, South and Southeast Asia, and the Middle East.

Resistance to third-generation cephalosporins — the last resort for tackling gonorrhoea, which infects more than a million people every day — has been confirmed in Austria, Australia, Britain, Canada, France, Japan, Norway, South Africa, Slovenia and Sweden.

Another case in point is MRSA — methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus — which has grabbed headlines due to a rash of outbreaks at hospitals.

Patients with MRSA are 64 per cent more likely to die than those with a nonresistant form of the bug, the WHO said.

In parts of the Americas, resistance to MRSA treatment had reached 90 per cent, while levels of 60 per cent were seen in Europe, the study found.