The deadly crusade to get ripped

SAM thought about his muscles all day every day. He woke up at 2am each night to drink protein shakes and injected steroids. He’s one of the lucky ones.

“THE fear I get is almost like this gravitational pull to go harder and harder and harder. And I have to be really conscious to make sure that doesn’t happen,” 40-year-old Sam* says.

For decades, his terrifying quest to be ripped was illusive. He never reached his goal, because the goalposts kept shifting.

“There was always something to try and work on,” he says, and it consumed him “all day, every day.”

From his late teens onwards, Sam undertook a punishing regimen that included hours of working out at the gym each day, an incredibly strict diet, taking supplements and anabolic steroids.

“The ones [steroids] that I was taking were intramuscular injections,” he says, “at one point I started taking insulin. If you don’t have diabetes and you take insulin, then insulin draws nutrients into your muscle cells.”

Even though Sam knew the insulin injections could actually make him diabetic — or worse put him into a hypoglycaemic coma — he didn’t care.

“So that’s how much risk I was taking and it didn’t bother me,” he tells me, “you just think you’re on top of it, you feel invincible in a way.”

Although Sam has never been officially diagnosed with so-called muscle dysmorphia — also informally known as “bigorexia” — he identifies with every single symptom of the condition (see the list below). People with muscle dysmorphia erroneously believe they are insufficiently muscular or insufficiently lean.

Like many men with bigorexia Sam is a smart and driven, high-achieving bloke. He understands just how much the compulsion to be more muscular has, at times, haunted not just his days, but nights too.

“I read you could increase your natural growth hormone by waking up in the middle of the night and having a protein drink … so I would set an alarm, get up at two or three in the morning, have a protein shake, go back to bed.”

At his heaviest, Sam got to 100 kilos and a tiny 8 per cent body fat. His quest to keep getting bigger only came to an end because he ran out of money.

“For the stuff that I needed it went from maybe $60 a month to $500 a month, in no time at all because of supply and demand.”

If not for that circuit breaker, Sam believes, “I’m sure it would have progressed to the growth hormones.”

One person who understands this story all too well is Dr Scott Griffiths, Research Fellow at the University of Melbourne. He’s an expert in male body image and in particular, male eating disorders.

Dr Griffiths points to the increase in the use of anabolic steroids in Australia and says: “All the evidence says that steroids are very, very effective and guys know this.”

Alarmingly, he believes the increasing numbers of steroid users is having a circular effect and adding to their popularity.

“The former taboo about discussing steroids out in the open is starting to melt away. If you know for a fact that there is a decent number of dudes at your gym who are on ‘roids then it stigmatises it less. You can have those conversations out in the open,” he says.

For Dr Griffiths, this is tightly linked to another concern: “Only around 10 per cent of steroid users in this country play any type of sport … which only leaves appearance for the reason for them to be doing it.

“It’s hard to think of that indicating anything other than muscle dysmorphia,” he says.

There is currently no published data on the numbers of Australian men suffering with this disorder, although Dr Griffiths says anecdotally and in clinical case reports it seems to be increasing.

“From data, the average amount of time that guys with muscle dysmorphia spend each day thinking about their muscularity or not being big enough or how to get bigger is about five and a half hours.

“The mental impacts are really severe depression, often social isolation and … a lot of anxiety. Once steroids come into the picture, the biological concerns shift to things like infertility, cognitive deficit, damage to the cardiovascular system and the heart,” he says.

Dr Griffiths says that society frequently mocks steroid users and body builders, which is one of the major reasons why men suffering bigorexia tend to keep quiet about it. As a rule, Dr Griffiths says blokes only reach out for help once their lives are falling apart.

“We almost only ever get to see these guys if the disorder has really taken over control of their life in all domains. It’s really impacting their ability to do their job, their relationship is teetering on the edge of dissolution or breakdown. If all their friends are worried,” he says.

It’s eight years since 17-year-old Matthew Dear died an excruciating death. But for his mother, the grief never subsides.

“It’s like a constant stabbing — a pain that’s always there,” Tina Dear, 50, says, “His bedroom is untouched. We can’t bring ourselves to touch his room.”

While Tina is the mother of five children, only four are living. On April 20, 2009 her beloved eldest son, Matthew, died in hospital after an extreme adverse reaction to anabolic steroids.

“Everything just started shutting down and he ended up with his brain swelling and crushing his brain stem,” Tina recalls.

Speaking from her home in Essex in the UK, Tina explains she had no notion her popular and hardworking son was taking steroids. He had a part-time job with Royal Mail, loved cars and dreamt of joining the British navy.

“He could run three miles at the drop of a hat [and] he would often go for a 13 mile run with a backpack full of bricks for the weight, so he was extremely fit.

“He didn’t smoke, rarely drank, and he was a marine cadet, and that was his dream —

be a real marine.

“When he said he wanted to join the gym, we thought the worst thing that could happen would be him dropping a weight or trying to lose too much weight,” Tina says.

Nine months after joining the fitness facility, Tina discovered this was far from the worst thing that could happen.

“It was somebody from the gym that actually sold him the steroids,” she says, “it’s like going into a sweet shop sometimes. Whatever type of anabolic steroids you want, they’re there.”

A week before Matthew died, he started to suffer agonising stomach cramps.

“He was rolling around in the bed with uncontrollable pain and that was horrendous to witness that. All of the organs started to shut down.

“He was stumbling around, he couldn’t see properly, he couldn’t get his balance, and … it was obvious there was something major going on there.

“We called an ambulance and that was the first time that we knew that he’d taken anabolic steroids,” Tina recalls, “a week after that he passed away.”

While Tina Dear doesn’t believe her late son, Matthew, suffered from muscle dysmorphia — his main aim was to get fitter and stronger — she acknowledges the increasing body image pressure on boys and men.

By way of example, Tina points to the original 1970s Star Wars figurine of Luke Skywalker. He was a plain-looking bloke in a white top. In contrast, she says, the modern version is super muscly.

With the influence of advertising and popular culture, Tina says “we don’t appreciate the pressure that young boys and men are under.”

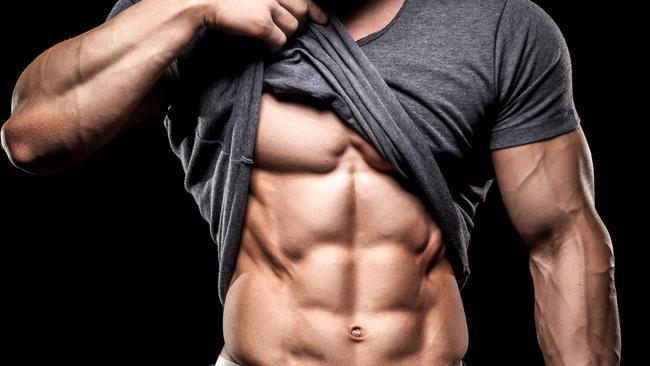

“They have so many images of what they’re meant to look like … they’ve got to have a six pack, you’ve got to look good.”

Despite the searing grief, Tina and her husband, Chris, and their remaining children decided to go public about Matthew’s death.

“When we lost Matthew we tried to make sense of it, to look into steroids and there was nothing out there,” Tina says.

According to Tina, the close-knit Dear family struggled to find publicly available information discussing the harm that steroids can do. This led them to create the Matthew Dear Foundation, in honour of their son.

“The only thing that you would find out is websites where it would tell you a little bit about steroids [and] the benefits of them, because at the end of the day, they’re trying to sell them,” she says.

Tina believes it’s vital to educate young people about the risks.

“I would encourage parents to talk to their children … and it’s got to start early,” Tina says, “At least they can make an informed choice then. You might get away with it but we try to say: ‘Is the risk actually worth it?’ You could end up like Matthew.”

Dr Scott Griffiths is speaking at TEDx Sydney on Friday, June 16.

Think you or someone you love needs help for an eating disorder? Contact the Butterfly Foundation via their website or call: 1800 33 4673

SIGNS YOU MAY HAVE BIGOREXIA OR MUSCLE DYSMORPHIA:

• Excessive time and overexertion in weightlifting to increase muscle mass

• Preoccupation and panicking over workout if unable to attend

• Overtraining or training when injured

• Disordered eating, using special diets or excessive protein supplements

• Steroid abuse and often other substance misuse

• Distress if exposed leading to camouflage the body

• Compulsive comparing and checking of one’s physique

• Significant distress or mood swings

• Prioritizing one’s schedule over all else or interference in relationships and ability to work

• Often other body concerns, hair, skin, penis size

(Source: The Body Dysmorphia Foundation in the UK)

* Not his real name

Ginger Gorman is an award-winning print and radio journalist. Follow her on Twitter @GingerGorman