You can’t see it but an impenetrable ‘Millennial Wall’ divides our major cities

It can’t be seen with the naked eye, but an impenetrable wall surrounds Australia’s major capital cities and blocks access to a huge cohort of people.

It can’t be seen with the naked eye, but an impenetrable wall surrounds Australia’s major capital cities and restricts access to a huge cohort of people.

Forming steadily over a long period of time, it’s been dubbed the “Millennial Wall”, segregating young people from Baby Boomer and Generation X strongholds.

An expert has plotted this invisible border in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, revealing the line that keeps younger would-be homebuyers at bay.

It paints a picture of the extent of the country’s housing affordability crisis – and the impacts of it go far beyond postcode preference.

WHERE THE WALL SITS

Demographer Bernard Salt took data from the 2016 Census for the 2310 suburbs across Australia, classifying each based on the age group of homeowners.

He then mapped the country to show the dominant generation in each suburb, to clearly identify the ones where Baby Boomers (born 1946 to 1963), Generation X-ers (born 1964 to 1981) and Millennials (born 1982 to 1999) came out on top.

Mr Salt, who compiled the data for a column in The Australian, told news.com.au there were clear patterns.

“The closest Millennials can get, where they dominate the homeowner cohort, is Burwood in Sydney and Sunshine North in Melbourne,” he said.

“Middle-Australia Millennials really struggle to overcome the 12km barrier to buy a home.

“Then they extend further and further out. As our cities have gotten bigger, these sharp divisions have become more entrenched.”

Our two biggest cities are like dart boards, Mr Salt says.

The bullseye is a cosmopolitan zone made up of city workers and students, then the “goat’s cheese curtain” of hipster enclaves, young professionals and other yuppies, then the outer suburbs.

“To some extent, this is what you’d expect – young people buy their first home in the outer suburbs, trade up in their late 30s and 40s to something bigger and better, before ending up in the prestige locations late in life,” he told news.com.au.

“I wonder whether that will happen. I wonder if Millennials have that same aspiration, if they buy into that narrative. I’m not convinced they do.”

MORE THAN PRESTIGE FACTOR

It’s not overly surprising that premium, waterfront suburbs have higher-priced property and are therefore out of reach for many younger buyers.

But the distance of the Millennial Wall from the CBD centres – that 12km barrier – shows how much housing affordability is restricting the choices for first homebuyers.

The drivers of sharp price growth are more complex than water views, explains Thomas Sigler, a senior lecturer in human geography at The University of Queensland’s school of earth and environmental sciences.

“In no particular order, it boils down to property investment and speculation, limited land supply/release, service economies being more centralised than manufacturing jobs, meaning there is a greater premium on proximity to the CBD, overseas investment and the financialisation of real estate more broadly,” Dr Sigler said.

RELATED: Sydney and Melbourne property markets remain hot … but for how long?

Also contributing to high housing costs are “perverse incentives on housing, such as negative gearing and capital gains tax … and the growth of (self-managed superannuation funds)”, he said.

“Also, there is a greater premium placed on living in a major capital city, as they have access to good schools, theatres, airports, hospitals and things that rural areas cannot provide.”

The classic supply-and-demand equation is being impacted by mobility trends, which Dr Sigler said has slowed to historical lows for many reasons. There’s more fierce competition among younger generations for limited housing – and older populations are “staying put”.

“First of all, more and more households are dual-income or dual-career, meaning that even if one partner gets a job elsewhere, they don’t necessarily have to move,” Dr Sigler said.

“Second, working-class or blue collar wages have not risen as fast as white collar wages, meaning the incentive for relocation is less and less. Fly in, fly out (employment) compounds this by allowing breadwinners to work remotely but their household to stay put.”

RELATED: National story of property prices is not reflective of many markets in Australia

The Millennial Wall raises interesting and important questions about growing social inequality and the potential consequences of such a geographic divide.

POTENTIAL CONSEQUENCES

At the start of the 1980s, more than 60 per cent of younger Australians aged 25 to 34 had bought their own homes.

Come 2016, that figure had slumped to 45 per cent on the back of skyrocketing property prices, a tougher lending climate and flat wage growth.

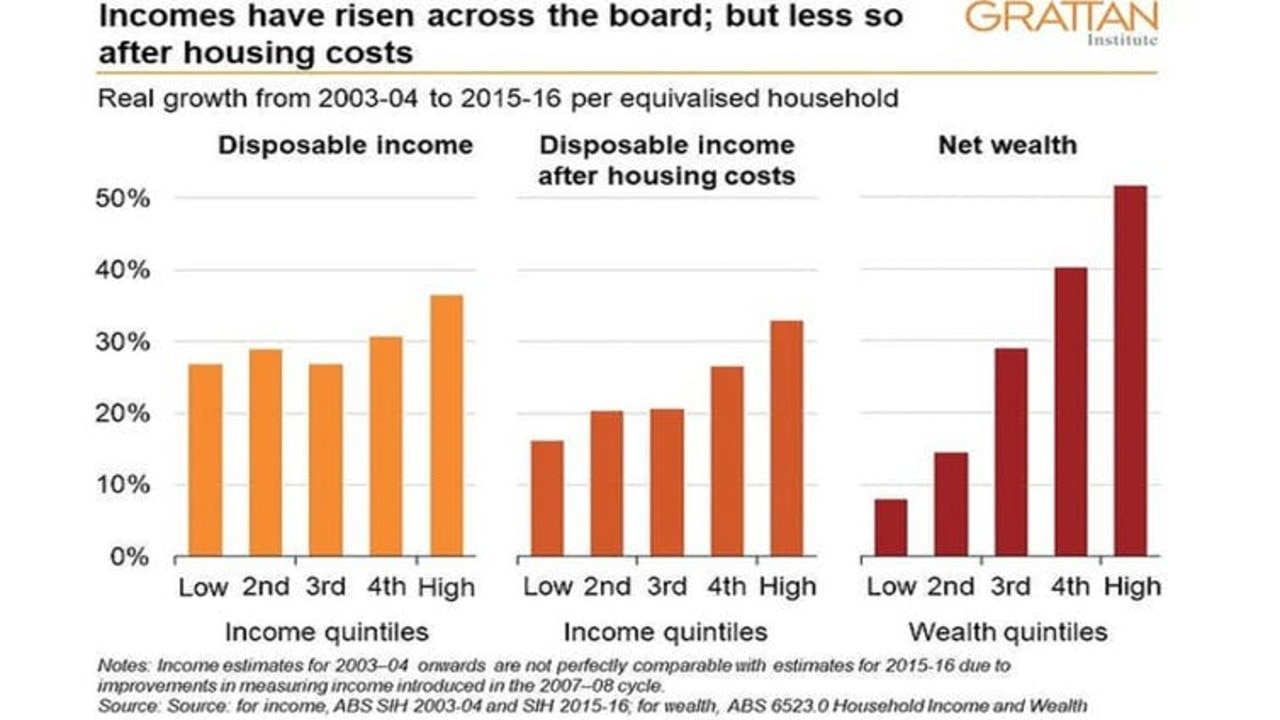

“The big winners of the property boom have typically been older, typically Australians lucky enough to buy a house before prices took off,” Brendan Coates, program director of household finances at the think tank the Grattan Institute, wrote in an article for The Conversation.

“Housing has thus compounded inequality between the young and old.”

But that inequality could morph in the future, with young Aussies with wealthy parents either benefiting from the “bank of mum and dad” or inheriting real estate.

“Many low-income Australians won’t be so lucky, which is why the share of Australians who own their homes is expected to fall sharply in the decades ahead,” Mr Coates said.

RELATED: Government’s first-home deposit scheme labelled a dud

When it comes time for them to retire, today’s Millennials are significantly more likely to be renters without a property asset to underpin their golden years, he says.

This week, Australian Bureau of Statistics data analysed by the ABC found retirees who owned their home were 20 times better off financially than those who rented.

“Despite the clear evidence housing is key to inequality in Australia, housing policy is thin on the ground,” Mr Coates said.

Addressing inequality demanded a clear strategy on tackling soaring housing costs, he said, and a good start was to boost Rent Assistance for low-income tenants.

“The federal government should also give more funding to the states for social housing carefully targeted to people at serious risk of homelessness,” he said.

But truly tackling housing inequality will only happen if prices fall – and that will take more new homes. A lot of them.

Mr Coates said the construction of an extra 50,000 homes each year for a decade would lower dwelling values – as well as rents – in the order of 10 to 20 per cent.