What the Australian Constitution doesn’t say is brilliant

THE Australian Constitution is not stupid or meaningless. On the contrary, its pointlessness is the whole point.

WHEN it comes to the Australian Constitution, Denis Denuto was right: It’s the vibe.

In fact it’s a shame that the legendary lawyer from The Castle isn’t advising the High Court right now. If he was we probably wouldn’t have the current constitutional crisis on our hands.

The truth is the Australian Constitution has very little to do with the day-to-day running of the country and almost nothing to do with who is in charge of it.

This was brought into sharp relief in 1975 when the Governor-General used his perfectly legitimate constitutional power to dismiss the prime minister and it was almost universally agreed afterwards that he should never do such a thing again.

In fact the prime minister, who is the head of the executive government and therefore supposedly the most powerful person in the country, isn’t mentioned by the Constitution at all.

According to the Constitution the Governor-General is the head of executive government and the prime minister doesn’t exist. And the fact that the PM is elected by the party with the majority of seats in parliament doesn’t exist either.

All of this happens purely by convention, because everyone from the PM to the voters who didn’t quite elect him sort of quietly accept — without even so much as putting it in an email — that it seems like the most sensible thing to do.

In other words, our whole government is based on a vibe.

But this doesn’t mean the Constitution is stupid or meaningless. On the contrary, its pointlessness is the whole point.

Much like the great blues guitarist Steve “The Colonel” Cropper, it’s the notes it doesn’t play that make it so special. It’s what it doesn’t say.

Other founding documents — including the most famous Constitution of all, that of the United States of America — set out the kind of country their authors want to create. The ideals are lofty and the language is poetic and that’s all well and good for a while.

But the problem is that while the times change and the countries change, the documents stay the same. As a result, the Americans have a clearly enshrined right to bear firearms that was drafted at a time when a citizen militia carrying single-shot rifles was its best defence against an 18th century king. Now it means that lunatics can obtain semi-automatic weapons to gun down school kids and country music fans.

The Australian Constitution, by contrast, merely establishes a framework for parliamentary democracy and then basically leaves it to us to muddle out the rest as we go along.

There is no grandstanding, no poetry, no lofty declarations. Much like our nature, it is a practical, no-frills approach that doesn’t tell us what to do, it just tells us how to get things done.

In other words our federation is built on the principle of “set and forget”. And, as a result, we have as a nation decided to muddle out the rest as we go along and only fall back on the Constitution as a last resort.

The people we give power to, the parties we elect and the government departments that often control our lives are all pretty much things we have simply allowed to evolve.

And that is its brilliance. This is ultimate democracy because it is truly government by the consent of the governed. It’s not the words set in stone that control us but our ongoing sense of who we are and what we value as Australians.

And indeed when the Constitution or other laws have come into conflict with those values we have historically risen up to change the law rather than ourselves, as we did with conscription and Aboriginal recognition and almost certainly will do with same-sex marriage.

And it is this that makes the current dual citizenship fiasco so frustrating and beguiling.

For within the skeletal sketch the Constitution has left us to colour are also some quaintly specific checks and balances that are both strangely progressive but also archaic remnants of their time.

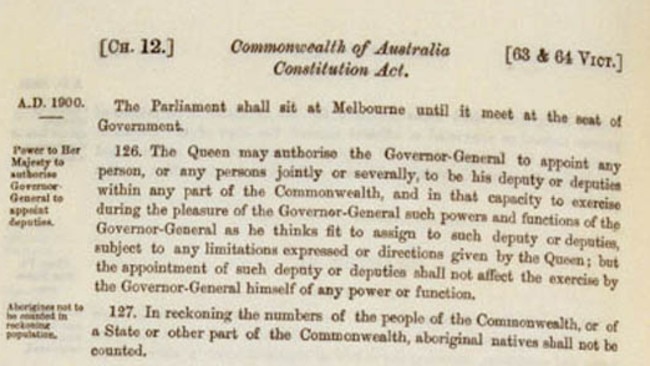

An obvious example is the infamous racial provision of Section 25 that states: “If by the law of any State all persons of any race are disqualified from voting at elections for the more numerous House of the Parliament of the State, then, in reckoning the number of the people of the State or of the Commonwealth, persons of that race resident in that State shall not be counted.”

By any modern reading that appears appallingly racist, however its intention at the time was quite the opposite. What the fathers of federalism were telling the states was that they could not deny Aboriginal people or others the vote for their own elections but then sneakily count them as part of the population in an effort to get more seats in the federal parliament. Far from being racist, it was supposed to be a penalty for racism.

Of course thanks to the referendum of 1967 there is no need for such absurd provisions now and the section is effectively meaningless. Little wonder the campaign to remove it has been all but completely subsumed by a push for more meaningful indigenous recognition.

Not so another quaint section that is threatening to bring down the whole government. This is of course the dual citizenship provision in Section 44, which states:

“Any person who is under any acknowledgement of allegiance, obedience, or adherence to a foreign power, or is a subject or a citizen or entitled to the rights or privileges of a subject or citizen of a foreign power…shall be incapable of being chosen or of sitting as a senator or a member of the House of Representatives.”

It’s pretty clear what that says and the High Court certainly thought so last week when it disqualified five out of seven dual citizen MPs from sitting in either house of parliament.

But, as we have seen from the experience of our indigenous brothers and sisters in Section 25, what a document says and what it actually means are often two very different things.

There is, as any lawyer worth his salt will tell you, often a gap between the letter of the law and the spirit of the law. And that gap is now a chasm that threatens to engulf not just the government but our whole system of government – so much so that both Liberal and Labor are shitting themselves at the prospect of a full audit of who belongs to where.

Firstly, let’s not all hold hands and sing Kumbaya here. There is a reason that Section 44 exists and it’s as obvious today as it ever was.

Say North Korea suddenly launches a nuke on us or our allies. Do we really want someone who is a dual citizen of Australia and the DPRK voting on how we respond? Or, for that matter, a prime minister who is a dual citizen of Australia and the US deciding on how far we support Donald Trump? Or a Chinese-Australian citizen who is Minister for Defence?

It is not too much to ask that whoever is representing us in the Australian parliament and the Australian government should have Australia as their absolute, unequivocal priority.

That is clearly the intention of Section 44: To ensure that those who serve the nation have no divided loyalties, no conflict of interest, no potential for coercion or compromise. It is clearly both a worthy and pragmatic principle and an obvious benchmark for any self-respecting nation.

However it is also equally clear that anyone who doesn’t even know that they are a citizen of a foreign country is pretty unlikely to hold such an allegiance. This is especially clear if they were not even born in a foreign country and/or if such citizenship was conferred upon them without their knowledge.

Any layman can see that but apparently not any lawyer. Instead the nation’s most pre-eminent jurists on the nation’s most preeminent legal body have chosen to apply the letter of the law instead of its obvious meaning.

It’s a shambolic situation and one the shambolic Denis Denuto could have easily saved the government from.

“It’s the vibe of the thing, Your Honour,” he once said.

He was right.