‘We can’t even @#$% things up properly’: Why we need a new party

AUSTRALIAN politics is broken and our leadership more at a loss than just about any other time in our history, writes Joe Hildebrand.

IN 1964, the historian Donald Horne scathingly described Australia as “a lucky country”, a nation which had skated by on good fortune despite being plagued by dumb leadership.

Naturally, the nation’s leaders entirely missed the point and “the lucky country” was proudly embraced as Australia’s national motto. Horne died in 2005 with his head in his hands.

Now, more than half a century later, our luck is finally catching up with us. Australian politics is broken and our leadership more at a loss than just about any other time in our history.

Both major parties have torched popularly elected prime ministers before they could even seek re-election. Not one of the past four prime ministers has managed to complete a full term in government. Landslide victories have been instantly converted into hung or near-hung parliaments.

Normally it would take some skill to @#$% things up this badly and yet there’s no evidence of that either. Even after each respective coup it quickly became clear that the new leader didn’t actually have a plan for what to do next.

Not only that, even after all the musical chairs and internal shaftings each party is now stuck with a leader that not only does the public not particularly like but the parties themselves don’t particularly like either. In short, Australia’s political leaders are so inept that they can’t even @#$% things up properly.

But Lord knows this doesn’t stop them trying. At the moment Bill Shorten’s sole mission on earth is to stop Malcolm Turnbull from implementing Labor policy. No doubt this is because if he did so it would expose the dirty little secret that is crippling Australia: In their political hearts, Bill and Malcolm are exactly the same.

Indeed they are so incredibly alike that Shorten has been forced to perform the world’s most unconvincing impersonation of Jeremy Corbyn and Turnbull the world’s most celebrated impersonation of Donald Trump just so they can find something to disagree on.

Meanwhile, the strongest argument doing the rounds for supporting Malcolm Turnbull isn’t that he can win the next election, nor even the next party room ballot, but that to change prime ministers again would be so excruciatingly embarrassing that even certain death is preferable.

And that is certainly what’s on the cards.

As I wrote last week, the PM is caught in a political death spiral — when he is harsh he loses the left yet it’s never harsh enough to satisfy the right. But when he swings back to his moderate roots with gentler policies, the right hates him even more and the left simply doesn’t believe him. For Turnbull, it is raining fire from all directions and there is no shelter to run to.

As a result, he is getting savaged in the polls, savaged on social media, savaged by the right of his party and his comrades on the left are savaging themselves — thank you Christopher Pyne.

By any political analysis he is a dead man walking and yet here is the rub: Turnbull is almost certainly the best candidate for prime minister in the current parliament.

For one thing, he is the only candidate who currently has the job and it’s about time someone kept it for longer than one of Taylor Swift’s relationships. In the past decade we have never given anyone a chance to become a good leader, let alone a great one. And with the world the way it is we need good leadership more than ever.

But the real kicker — the staggering, maddening, unbelievable hair-pulling fact — is this: Despite the barrage of flak he has copped from all sides, what Turnbull is doing is actually enormously popular.

For example, his levy on the big banks is supported by a whopping 61 per cent of the population compared to just 16 per cent opposed, according to a recent Sky News/Reachtel poll.

And according to Newspoll, 54 per cent of people support his National Disability Insurance Scheme package so much that they are prepared to pay a 0.5 per cent increase to the Medicare Levy.

Yes, this is a policy so popular that 54 per cent of people support giving themselves a tax hike. In normal circumstances this would make a party room wake up at dawn so they could check if the sun actually shone out of their leader’s arse.

But it gets better: The PM’s flagship Gonski 2.0 schools funding package is even more popular still. According to a Fairfax/Ipsos poll it is supported by — and this is not a typo — 86 per cent of voters.

In fact it is even more popular among Labor and Greens voters and they’re the only two parties that tried to block it. And we wonder why people hate politics.

So there you have it: The PM’s three signature policies all have landslide-level support and yet if an election were held today the government would lose in a landslide of 47 to 53 per cent.

Looks like the lucky country is getting what it deserves.

So why is there this shambolic disconnect between what people want and who they vote for?

The defining seismic shift in politics over the last decade has been an extremely vocal and growing minority peeling away to the fringes, fuelled by a massive sense of disillusionment with established political and media institutions.

These hardcore believers have been emboldened by new “information” sources and a virtually unlimited and unfiltered capacity for self-expression online. It is impossible for all but the most naive not to see that the sudden political upheaval we have seen in Australia, the UK and the US has correlated entirely with the exponential rise in social media use. And just like Donald Horne warned, established political leaders have been caught napping.

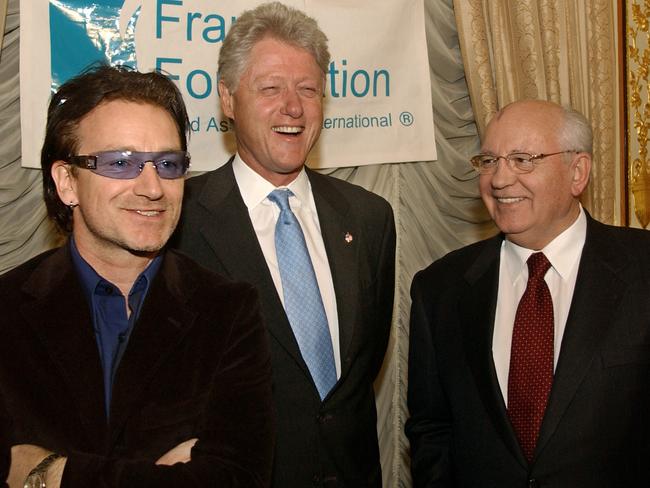

Previously political activists on both sides would lament the drift to the centre of both major parties and the lack of a real choice, a complaint that was echoed throughout the UK, the US and Australia during the Blair, Clinton and Hawke-Keating governments.

Now, however, it is the populist extremes that are dominating political debate as leaders are beholden to the newly empowered ideological rump of their respective parties. The tails are wagging the dogs.

Yet the thing that has escaped unnoticed is that this phenomenon has been most pronounced only in countries controlled by the two-party system, such as the UK, US and here. This once blessed political convention, which evolved organically to provide governmental stability, is now being stretched to breaking point.

For here is the catch: Leaders of centre-left or centre-right parties have to adopt the language and often policy of the hard-left or hard-right in order to stop their party’s “true believers” from splintering off at the fringes. If they fail to appear hardcore enough they lose not only votes but vital activists and election campaigners.

Yet all the simplistic and politically charged sloganeering isolates moderate party supporters and swinging voters, who become increasingly disillusioned and disconnected from the political process. And it is these people who still make up the vast majority of the population — which is why political parties drifted to the centre in the first place.

Now the sensible centre is still out there, still in the majority, but has nowhere to go. This is an appalling result for both democracy and stable government.

Let us say that the political spectrum is roughly divided into five quintiles: Hard Left, Centre Left, Swinging Voters, Centre Right and Hard Right. The hard left controls the centre left and the hard right controls the centre right and the swingers are left to choose between the lesser of two evils.

Thus a group that represents just 20 per cent of the population ends up running the country while the 60 per cent of voters who want a centrist government go unrepresented — a profoundly anti-democratic result.

Tellingly, the Labor Party factional system has done this incredibly efficiently for years. A powerbroker would need only have enough supporters to control a key sub-faction of the Right, then that sub-faction would control the faction and then that faction would control the caucus — even though the actual number of MPs loyal to the powerbroker is only a small minority of the caucus overall.

However the factional system was often a bulwark of pragmatism against extremism and used to support stable leadership. Once an ideologically-driven minority controls things it is far more unstable: Whoever wins has no choice but to be either extreme or extremely disappointing and promptly gets either rolled or voted out and their policies reversed by the next lot. And so not only is such minority rule undemocratic but nothing ever gets done — the worst of both worlds.

And of course ideologically-driven minorities can also harm the interests of the very party they serve. Conservatives who have refused to allow a free Liberal vote on same-sex marriage have not only toppled one of Turnbull’s strongest pillars of appeal but have also undermined the “Liberal” brand — a recent Reachtel poll found voters in 12 Coalition seats all supported same sex marriage but their elected representatives aren’t allowed to vote for it. This is the very definition of madness.

And so Turnbull and Shorten are both losing votes to both the left and the right, yet it is only those voices on the extremes who are being listened to. Left-leaning Liberal supporters and right-leaning Labor supporters are ignored, as are swinging voters in the middle, even though combined they still represent the overwhelming majority of overall voters. Little surprise then that the retreat of both leaders to their respective extremes has seen a decline in their primary vote, which is the other great paradox: The more the parties appeal to their so-called “base” the smaller the base actually gets.

Thus the once all-powerful two-party system has entered its own death spiral: Neither party can be broad enough to win majority popular support or deliver measured policy without losing the polarised hard core who rock up at all the meetings and hand out all the how-to-vote cards.

The US Republicans found this out the hard way when they discovered they could no longer control their own grassroots, who preselected Donald Trump despite the party’s best efforts and then combined with traditional working-class voters to make him president while the Democratic party was passed out in a penthouse somewhere. Trump may well be a fool as president but even that fact alone makes bigger fools of the Republican and Democratic establishment.

Likewise UK Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn defied the commentariat to demolish Theresa May’s prime ministership while at the same time falling well short of providing any credible alternative. Like Trump, Corbyn is a product of the angry and contradictory forces that drive politics today: Laughed at by his colleagues, endorsed by less than half the voting population, yet so zealously backed by his supporters that he is immovable as leader. The political ground is shifting and the major parties are like skyscrapers that have so long dominated the skyline: When the big one comes they must bend or break.

Yet the quake has only really shaken the three countries where the two-party system was once unshakeable. In three party systems, the shock has been absorbed.

It is tough to admit it but the once widely derided European-style tripartite system has actually been incredibly effective at diffusing the lurch to the extremes that we have seen here and in our two major allies.

Over the past two years, as the UK, US and Australia were rocked by rogue poll results, two other major Western democracies weathered the radical surge without batting an eyelid — including one nation more beset by both Islamist extremism and right-wing nationalists than perhaps any other.

In Canada, the centrist Liberal Party surged through the middle at the 2015 election to win majority government from the Conservatives at the expense of the Democrats. To give you an indication of this reasonable revolution, the Liberals went from 36 to 184 seats — a swing of more than 20 per cent.

But sure, I know what you’re thinking: It’s Canada — who the @#$% cares?

Fair point. Yet across the Atlantic in France a brand new centrist party that hadn’t even existed a year earlier came from literally nowhere and seized the presidency from the Socialists at the expense of the hard right and went on to win a landslide majority in the parliament.

Both these victories were far more overwhelming than either Trump’s win or Corbyn’s surprise showing — or either Turnbull or Shorten’s result at the 2016 election for that matter. The sensible centre may speak softly but it carries a big stick.

Of course there is something faintly nauseating about both Emmanuel Macron and Justin Trudeau, not least of all the fact that they both look like Thunderbirds, but surely that is a small price to pay for a head of government who doesn’t handshake women by the p***y or hang out with Hezbollah?

In Australia a rational, sensible, centrist government is closer than you’d think. We all know that Malcolm Turnbull flirted with the idea of joining the Labor Party and according to some his last Budget proves he secretly did.

Indeed, the golden age of Hawke and Keating was once considered so quintessentially balanced between economic advancement and social fairness that in 1987 Labor was dubbed Australia’s “natural party of government” by a young Brisbane barrister called George Brandis.

The truth is that most intelligent people in Labor and Liberal in fact think very similarly on most major issues because if you look at most major issues there is usually a clear intelligent response.

Turnbull has adopted the position on schools funding and the NDIS established by Labor, just as Tony Abbott initially did, while Labor has tried to make political hay out of abandoning its own policy. Whether using schoolkids and the disabled as political footballs was worth it or not is a question they will have to answer to their maker when the time comes.

Either way, it’s all pretty low. Or “second rate” as Donald Horne scornfully put it. Surely the time has come for the better minds of both parties to cut the bullshit, stop manipulating the basest instincts on both sides of the spectrum, and offer a unified position on the most vital issues facing the nation. Saving schoolkids from unemployment and the disabled from poverty would be a pretty obvious place to start.

It is time for a new third way to fill the void abandoned by the Labor Party and to which moderate Liberals are naturally aligned. I suggest calling it the Eureka Movement, in honour of the energy and fire that fuelled our first great push for liberty.

Fittingly, it was also a rebellion which combined the best of the left and the right — fairness for working people and resistance to oppressive government. And it already comes with a good-looking flag.

Donald Horne may still be turning in his grave but as Victor Hugo once said: “All the forces in the world are not so powerful as an idea whose time has come.”

It is time for a new party, a new movement, to put the national interest ahead of factional interests. Government by the best and brightest, elected by all instead of manipulated by extremists.

And if that is not an idea we are ready for then it is an idea we don’t deserve.