’Embarrassingly public setback’: Xi Jinping rocked by string of failures as economy tanks

Xi Jinping’s leadership is showing signs of strain after a chain of catastrophes including a tanking economy and a major political scandal.

The ousting of a “captain’s choice” minister. A tanking economy. Increasing international isolation. A chain of climate catastrophes. All have shifted the spotlight to Chairman Xi Jinping’s leadership.

And how well he weathers the next few months depends on how effectively he has consolidated his vast power over the past decade.

“In a closed system like China, many problems can be kept from the public,” Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) China analyst Ian Johnson said.

“But Xi’s defeats are setbacks that all Chinese people can feel and see.”

And his tally of defeats is growing.

He prominently backed Russian President Vladimir Putin just days before the bungled invasion of Ukraine.

His draconian Covid lockdown policy was suddenly revoked – without explanation or a nationwide vaccination campaign.

And the much-touted economic bounce back it was supposed to trigger has instead resulted in recession.

Now, his tightening grip over the Chinese economy has produced a retreat in foreign investment and paralysed local industry.

“Economic growth numbers can be fudged,” Johnson said.

“But, ultimately, people know what they know – and they know that they have less money in their pockets.

“The strange departure of Qin Gang as Chinese foreign minister is another public setback for Xi, a sign that his run at the top has run into serious difficulties.”

It’s precisely not what Xi has been working so hard towards during his decade in power.

Western media said Qin Gang's removal from his post is an embarrassment to Xi.

— Ma Dashuai (@machinpl) July 27, 2023

What a weird logic.

It is a proof that China's political system is one of meritocracy, since even someone who is "handpicked" by Xi could be dismissed if he proved to be no longer fit for his job. pic.twitter.com/KCOtbX1sN5

“What matters for Xi is not winning a popular vote but controlling key instruments of authoritarian power, namely the military, the security services, the anti-corruption apparatuses, the personnel department, and the propaganda machinery,” Asia Society Policy Institute China analyst Neil Thomas said.

“On this metric, surrounded by people he chose, Xi’s dominance has never seemed so pronounced.”

Dominance, however, does not equate to all-pervading competence.

“One factor unites these failures: a sense that Xi is increasingly isolated and no longer listening to the excellent advice he could get from the Chinese bureaucracy,” Johnson said.

But don’t expect Xi to lose his vice-like grip on China’s top job for some time yet.

“He has clear-cut so much opposition that he will not face any challengers,” he added.

“But these setbacks will likely be seen as signs that Xi’s administration is cut off from society and ossifying – becoming hardened and brittle and leading the country away from the dynamism of past decades.”

Game of Thrones

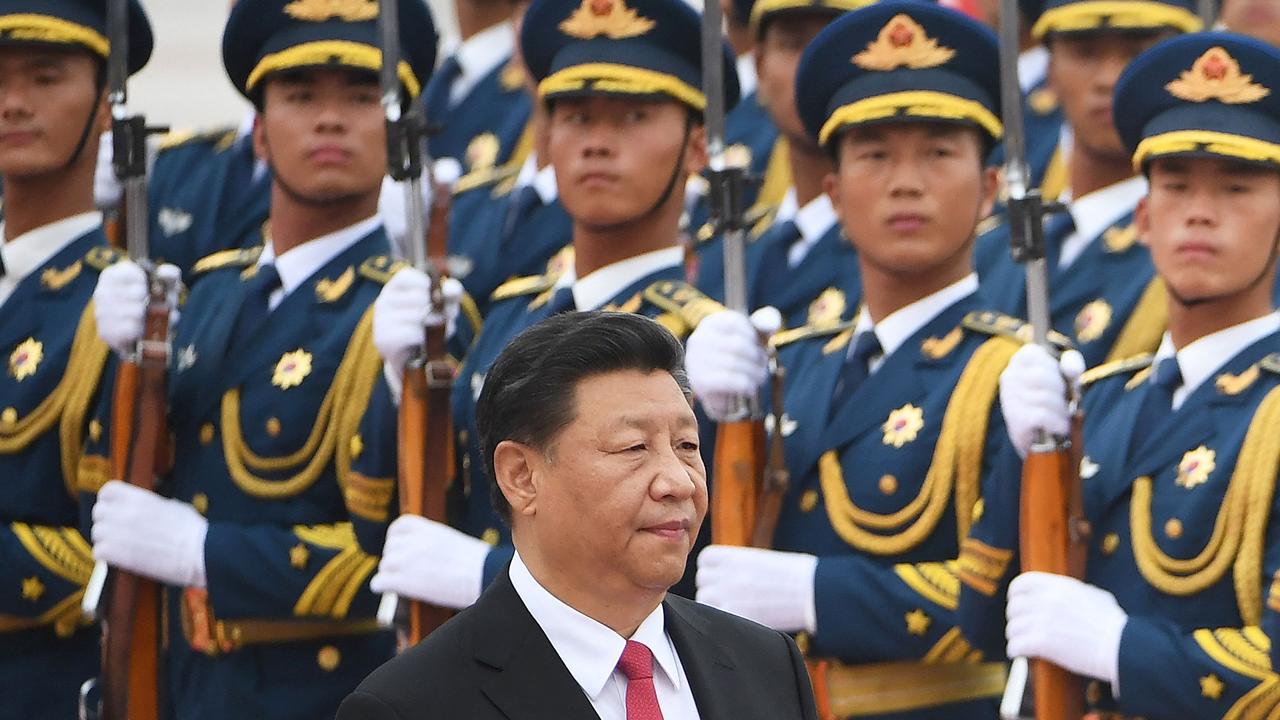

Xi has secured himself as China’s new emperor in all but name.

And he’s done so through a steady campaign of toppling any potential political challengers.

“As China’s economic and diplomatic challenges continue to grow, so too does Xi’s grip on the party,” Thomas said.

“He engineered the retirement of any lingering political rivals at the 20th Party Congress (last year) and filled high-ranking posts with loyalists.”

The chances of any direct plot to topple him as the sole leader of the single-party state now appear remote.

But Xi’s loyal supporters also have their own ambitions.

This has produced the emergence of what Thomas calls “sub-factional” rivalries.

“Xi has assembled a leadership team with representatives from groups of officials who used to work for him in different provinces and rode his coat-tails into the party centre,” he said.

“This arrangement appears to help Xi ensure that no one else becomes too powerful, as he can play allies off against one another, even though such tactics may come at the expense of stable and predictable policymaking.”

Foreign Minister Qin appears to be the first high-profile victim of this deadly game.

“The truth will eventually come out – it usually does in China, although it sometimes takes months or years,” Johnson said.

“But the way he was dismissed makes it unlikely that it was for health reasons.”

He says the way the Beijing government went into “silence mode” and then dumped Qin with a one-line announcement was typical of how the Chinese Communist Party deals with an internal crisis. The fact his achievements were also erased from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs website suggests his replacement – his predecessor Wang Yi – wants to distance himself from Qin’s faction.

“The key point is that Xi Jinping has suffered yet another embarrassingly public setback, one in a string that calls into question his judgment as he now rules alone at the top of the party,” Johnson concluded.

Battling market forces

Xi’s China is in a far worse position than when he took office in 2012.

The economy is struggling. Domestic confidence is faltering. Debt is ballooning. And China’s international status is suffering from repeated incidents in the Himalayas, East and South China Seas, and around Taiwan.

But Xi’s personality-driven politics don’t appear to allow any solutions.

“Policymaking is becoming increasingly volatile as China’s mounting challenges lead Beijing into deeper swings between the politics of its ideological agenda and the pragmatism of delivering a baseline of economic growth,” Thompson said.

Johnson added that the persistence of these problems results from “his allergy to market-oriented reforms”.

“Discussion of economic policy is more tightly proscribed than in any period since the start of the Reform and Opening-up era in the late 1970s,” he said.

It’s all about security.

Not national security. But Xi’s security.

“The party needs to supervise the whole economy to protect its security,” Thompson said.

In April, the Central Comprehensively Deepening Reforms Commission (CCDRC) resolved the party must determine “for whom to innovate, who should innovate, what to innovate, and how to innovate”.

The party, it said, would be responsible for “holistically planning the whole chain of technology innovation”.

Securitising everything

When Xi ascended to his unprecedented third term at the 20th Party Congress in October last year, he had one clear message for his hand-picked audience.

He said that national security should “permeate every aspect and the whole process” of government.

He reinforced that message at the May meeting of his Central National Security Commission. “The complexity and enormity of the national security issues that we are currently facing have increased significantly,” he said.

“We must adhere to bottom-line thinking and worst-case-scenario thinking and get ready to undergo the major tests of high winds, rough waves, and even perilous, stormy seas,” he added.

The world is already seeing what this means.

Foreign firms have been raided. Espionage laws have been expanded to cover businesses. Export and import controls have been imposed on key products and materials.

“Xi’s rising focus on security seems driven mainly by a belief that China must reduce its economic and technological dependencies on the United States and its allies in an era of intensifying geopolitical competition,” Thompson said.

But it’s also being directed at his own people.

Private tutoring has been banned. Access to online video games has been restricted. Even AI developers have been told their products must staunchly support Communist Party policies.

“Xi is not anti-business or anti-market. He is simply pro-party,” Thompson said.

“He wants to better harness private-sector activity to advance his goals for the party-state.

“The worry both inside and outside China is that security policies will compound the surprisingly rapid slowdown in China’s post-Covid recovery and hamstring the country’s economic trajectory.”

The centre cannot hold

“Xi is the decisive actor in personnel and policy decisions, but people on the ground suggest that a fierce competition is unfolding behind the scenes between networks of Xi-aligned cadres,” Thompson said.

That means Xi will likely have to intervene more often.

And that means any outcomes will inevitably be pinned on him.

The demise of Foreign Minister Qin was marked by the adoption of a new law on July 1 that places even further control over foreign policy in Xi’s hands.

And this will enable him to “take, as called for, measures to counter or take restrictive measures against acts that endanger its sovereignty, national security and development interests in violation of international law or fundamental norms governing international claims”.

It also points to his tendency to take more power upon himself as those around him fail to live up to his standards. And he has plenty of those.

Xi Thought is now compulsory reading for all Communist Party members. Its 14 fundamental principles were written into the Chinese constitution in 2017.

But, like all doctrinal treatises, it’s subject to interpretation.

It’s also incomplete. The first two volumes of Xi’s “selected works” were published in April this year. They contain 146 essays and speeches he issued between 2012 and 2022.

But exactly which of the 40 stand-alone books he has published are considered canon components of his testament remains unclear.

Any confusion over such orthodoxy could produce political schisms. And this would further weaken Beijing’s already restrained capacity to govern, Thompson added.

More Coverage

“Confusion will rise, with Beijing periodically switching its emphasis between growth and security, and Xi’s economic and security teams each vying for the upper hand,” he said.

“The continued centralisation of power and tightening of policy execution mean that slight shifts in messaging will ripple through the bureaucracy even quicker, more frequently, and more damagingly than before.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel