Why everyone will want to work for this New Zealand company

THE introduction of a major perk for employees at an unsuspecting New Zealand company will have people scrambling to apply for a job.

AT FIRST it may seem like working for this New Zealand company would be like any other ordinary office job, but the introduction of a crazy new perk will have jobseekers scrambling to hand in their applications.

Perpetual Guardian, a company that manages wills and trusts, has made a major change to how its working week is run, and it’s one many workers can only dream of.

Starting from November 1, Perpetual Guardian’s more than 240 employees will have the option to work just four days a week while still earning their regular five-day pay.

The decision to make the shift to a shortened work week while still keeping staff on the same pay followed an extremely successful trial earlier in the year.

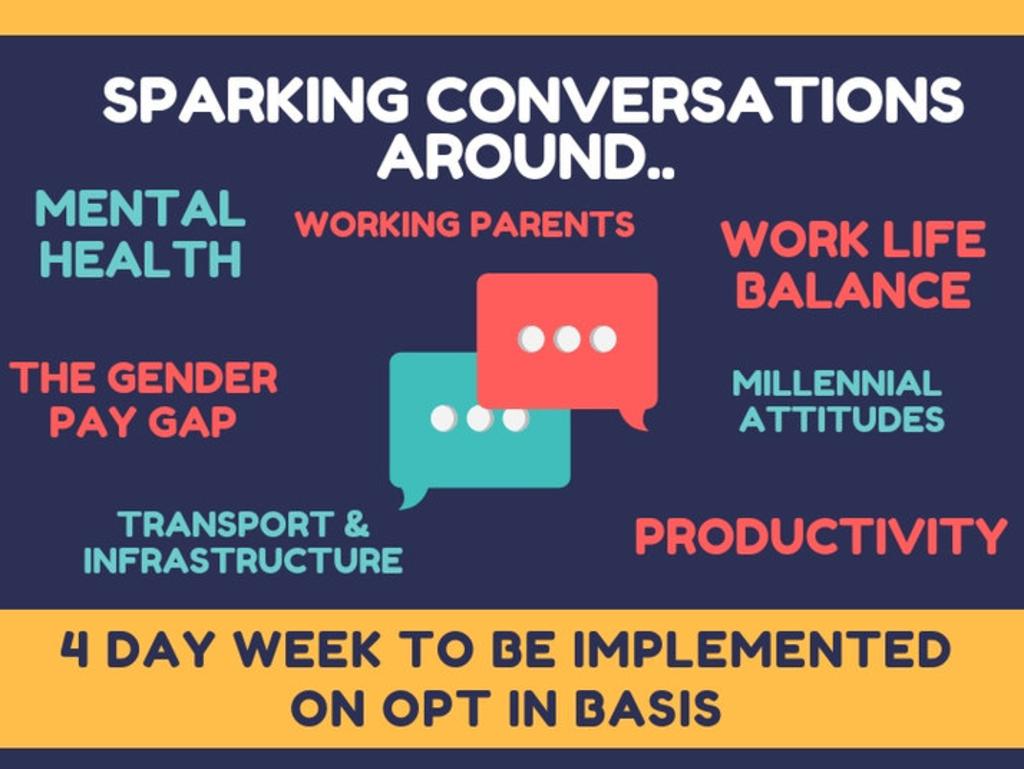

The experiment spanned two months starting from March and by the end of the trial the firm saw drastic improvement in work-life balance, productivity, engagement and lowered stress levels.

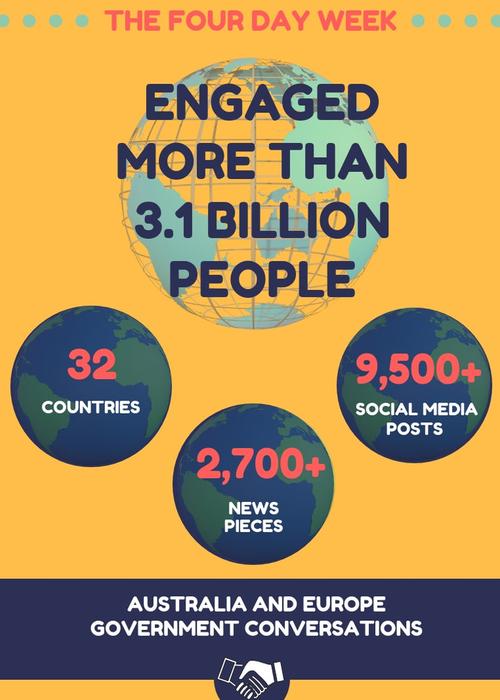

The company has since been contacted by organisations from more 50 other countries from around the world seeking advice on the best way to implement the four day week.

The UK’s Trade Union Council has even included a call for businesses to switch to the innovative work format into its report on changes that can benefit current and future workplaces.

The report said giving employees a four-day week while still maintaining their current pay and benefits should be a goal for all 21st century workplaces.

Founder of the New Zealand company, Andrew Barnes, said there had been no negative side to changing to the shorter week.

“For us, this is about our company getting improved productivity from greater workplace efficiencies,” Mr Barnes said.

“The productivity measures set and monitored by our leadership teams confirmed we achieved this.

“Importantly, the researchers ascertained that our staff’s wellbeing and engagement also improved through the trial.

“There’s no downside for us in going ahead with this.”

The change to the four-day week will be available to the staff on an opt in basis, with those choosing to do it provided with a weekly “rest day”.

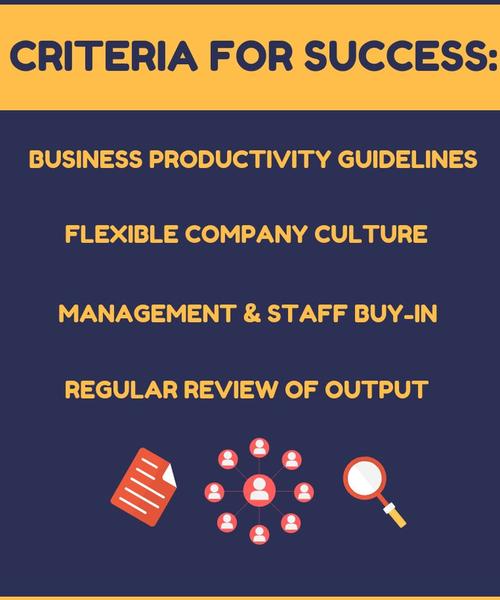

Employees will be paid the same salary as before and they will be expected to meet their weekly productivity objectives in order to continue to be eligible for the shorter week.

Staff will also continue to accrue annual leave and keep their entitlements.

The results from the trial showed employees working four days a week were more willing to put in extra effort to get their work done on time.

The change also had a major impact on work-life balance satisfaction, jumping to 74 per cent after the trial to 54 per cent before.

Before the trial began, there were concerns that reducing the time employees had to get their work done would increase stress levels as they would feel under more pressure, but results showed that staff stress actually decreased by 7 per cent.

Employees who choose not to opt in to the four-day week may still be able to negotiate flexibility in their hours across the five-day week.

For example, they may be able to start or finish work earlier to miss rush hour or work around school pick-ups.

“The opt-in process is individual, not team-based, so each team will establish a workable plan to accommodate their members’ needs,” Mr Barnes said.

“The right attitude is a requirement to make it work — everyone has to be committed and take it seriously for us to create a viable long-term model for our business.”