47-minute phone call before tradie’s suicide

A tradie who tragically took his life at work made one final call to his employer asking if he could take the day off as he felt unwell. Their response has left his family enraged.

EXCLUSIVE

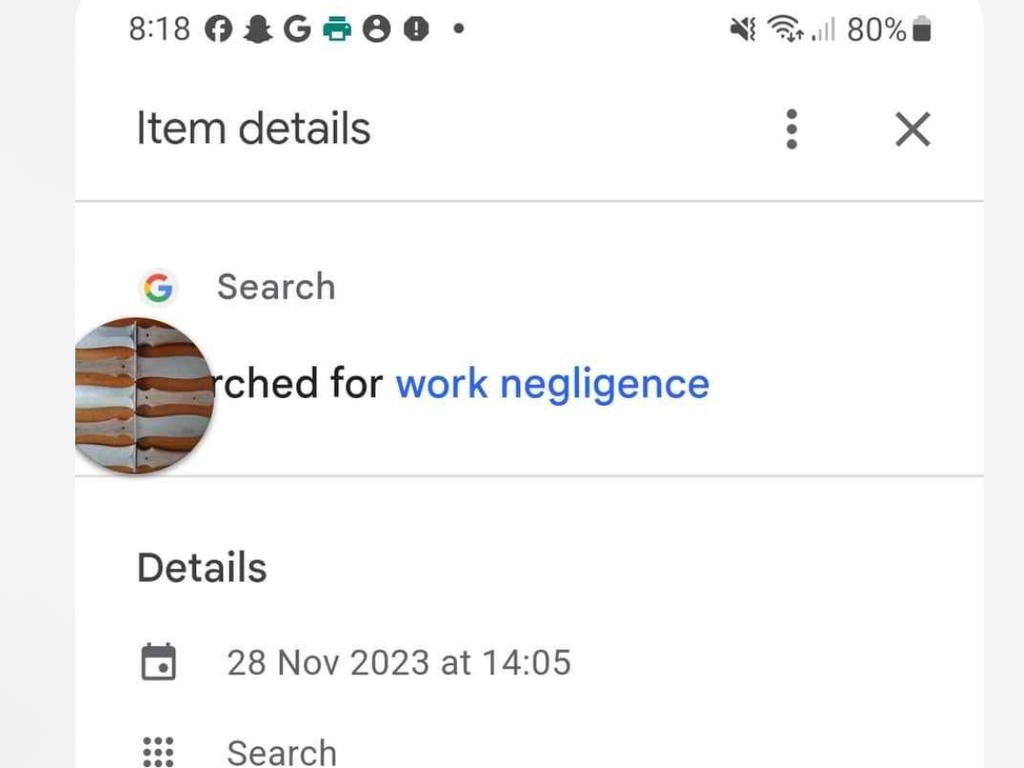

On the day Sam Keast took his life, he Googled “work negligence” while on the phone to his boss.

Phone records show it was the final call the beloved tradie would make on his work mobile, and the last time anyone would hear him speak.

He had already spoken to his employer about taking the day off because he was feeling unwell – only to be told he had to finish one more job and do a delivery the next morning.

The next day never came for the 27-year-old carpenter, who was found dead in the Melbourne factory he had been manning alone for months.

His grieving sister Serena believes his final Google search was the closest thing to a suicide note he could muster and now wants answers after his “avoidable death”.

In a staggering battle, she has since discovered the company did not report her brother’s death to health and safety regulator WorkSafe.

It wasn’t until she filed an official application for a mandatory investigation, nine months after his suicide, that the wheels were finally set in motion.

Now, WorkSafe Victoria is carrying out an investigation to determine whether PGC failed to protect the health and safety of Sam.

Here is Sam’s tragic story.

‘A fresh start’

Sam started working for Playground Centre (PGC) in the dispatch and carpentry departments of their facility in Whanganui, New Zealand, in 2018.

The company builds and supplies large-scale playground equipment for parks and schools, mostly in New Zealand and Australia.

“He was really good with his hands,” his sister told news.com.au.

“He had a good eye and was very imaginative. He was a solutions guy I suppose you could say. He thought outside the square, that’s why they liked him, that’s why he worked so well for them.”

In 2022, the company planted the seed that he would be a good fit to move overseas to establish a workshop in Melbourne in a bid to streamline service for their Aussie customers.

Ms Keast said Sam saw the move, which came as he dealt with a bruising separation from his wife, as a chance for a “fresh start”.

But there were red flags before he even left the country.

In an unsettling voice message sent the day before he flew out of New Zealand on September 15, 2023, Sam was given vague advice about his salary by his employer.

“We’ll keep paying you, umm, as per normal in New Zealand for the next two to three months. So you’ll just need to transfer the money across to your Australian account,” the recording said.

“We’ll bump your wage up a bit so you’re not losing anything in the exchange rate.”

Two days later, after he arrived in Australia, he received another troubling voice message from his employer encouraging him to “suss out where the nearest medical centre is.”

“Just a bit of forward thinking – for instance, when at some stage if you need to make a doctor’s appointment, or you know, if there was a, if um, if you did have an accident of some type,” the recording said.

“So just so you know roughly where to go.”

Ms Keast said her brother quickly found himself disillusioned, being made to work long hours alone in a factory in the city’s far outer west.

“He was supposed to just set up the office and help with a bit of customer service,” Ms Keast told news.com.au.

“They had a few bits and pieces breaking so they needed, you know, a guy on the ground that could be the face of the company.

“And then it sort of turned into he was having to do everything. They really should have had six to eight people there.”

Ms Keast recalled a conversation with her brother where she joked he must have been earning some good overtime after discovering he was regularly working long, seven-day weeks.

“No, this company doesn’t do overtime,” he told her, before admitting he’d be “fired on the spot” if he brought up the prospect of claiming overtime or joining a union.

“He became exhausted and isolated,” she said.

Things were so dire that he resorted to moving into a share house after work stopped paying for his short-term accommodation – despite repeatedly assuring him they would assist with his rent.

“This was during a rental crisis,” Ms Keast said.

“He wasn’t being paid in Australian dollars, he didn’t have an Australian contract to show anybody … he was devastated that he had to go back into a sharehouse.

“It was backwards for him, he had already married and lived by himself with his wife, he thought he’d gone past that part of his life. But he did it anyway.”

Do you know more or have a similar story? Email daniel.peters@news.com.au

Harrowing Google search

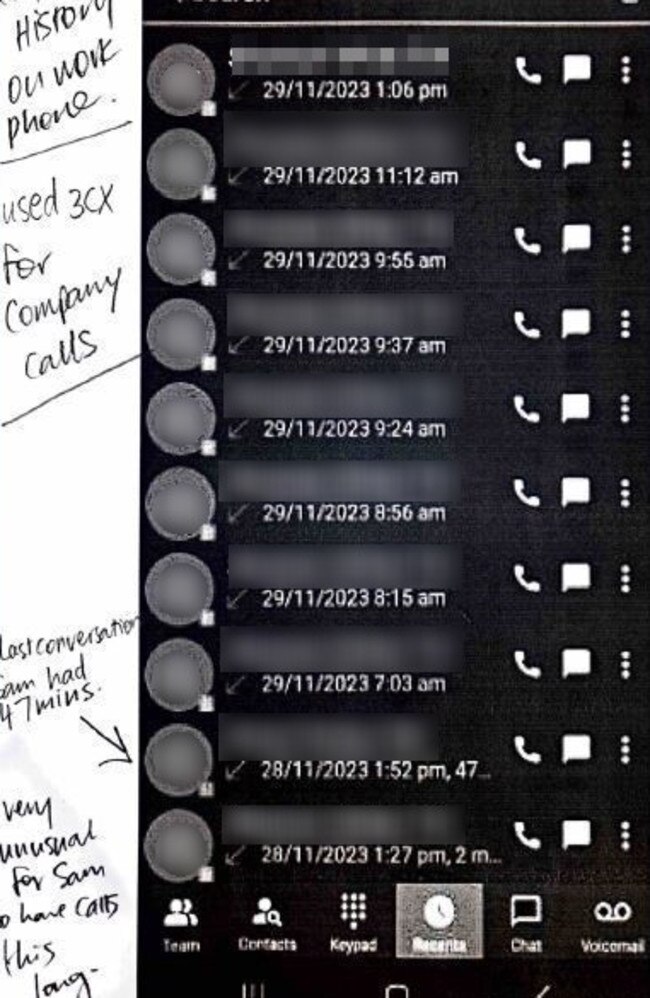

At 1.27pm on November 28 last year, just two months after moving to Australia, Sam telephoned a colleague at work to say he was sick.

In a statement provided to Victoria Police as part of a coronial brief, seen by news.com.au, the colleague who took the call referenced the two-minute conversation the pair had.

“Thought he was getting sick and a bit tired. Was told he could have the next day off after he had done a delivery first thing in the morning,” the colleague said.

Not long after hanging up, Sam made another phone call to a separate colleague.

That phone call lasted 47 minutes.

Sam’s sister is desperate to know what the pair spoke about.

After recovering his work phone and personal phones, she discovered he made a single Google search during their conversation with just two words: “work negligence”.

In their statement to police, the second colleague said they had a “work-related” call to Sam, recalling that “during the conversation he said he was ‘sick’ ”.

The colleague claimed that conversation took place on the morning of November 29, but phone records show it was actually on November 28.

“I personally suspect that the Google search for ‘work negligence’ is the closest to ‘suicide note’ that Sam could muster in his ill state,” Ms Keast said in her submission to WorkSafe.

“Sam believed that PGC would ‘do right by him’ (Sam was always a ‘glass half full’ kind of guy’),” she continued.

“He had let many things slide putting these down to teething issues.”

Ms Keast is convinced her brother took his life shortly after that phone call.

Police were only called to the workplace the following afternoon when PGC staff became worried that they were unable to contact him.

A welfare check was conducted at the factory and police were called immediately after Sam’s body was discovered inside.

It’s understood internal CCTV cameras, which were supposed to be installed as a way for the New Zealand-based company to monitor Sam and make sure he was safe, were not operational.

Why was Sam’s death never reported?

Sam died on November 28.

Ms Keast first reported his death to WorkSafe New Zealand on November 30 online, two days after his death, but heard nothing back.

When she followed up again last month, the government-run regulator said there was no record of Sam’s death ever being reported to them.

“We are unable to find any notification for the death of your late brother under Playground Centre Limited,” they told her in an email.

A furious Ms Keast prepared a thorough submission and applied for a mandatory investigation to be completed into his death.

On September 2, a full nine months after his death, WorkSafe Victoria confirmed they would carry out an investigation to see if PGC was at fault.

As part of her submission to WorkSafe, Ms Keast said she felt her brother’s job was to blame for his death.

She claims PGC failed to provide a safe environment, allowing him to operate in total isolation with heavy machinery and “no effective supervision”.

No history of mental illness or depression

One thing is abundantly clear from statements filed by Sam’s family members and friends: he was a young, healthy and happy man who had never shown signs of taking his life prior to his death.

“I believe the way PGC treated Samuel is the leading factor in Samuel taking his life,” his stepmother told police.

“Samuel’s state of mind was stable and in the days leading up to his death showed us no signs of mental health, struggling … neither in the months and years before this.”

His GP told police the same thing, recalling how Sam met with a counsellor on several occasions to discuss his mental health,

“I always found Sam to be very good at self-reflecting and had good coping strategies to help his mental wellbeing,” he said.

“He last saw a counsellor on 19 December 2022 and at this stage his mental health was very good and no concerns were raised.”

Ms Keast said her brother – who she described as “always happy” – was extremely resilient and had endured a lot of hardship in his youth.

“He was always happy to talk to anybody … everybody loved Sam. He was really beautiful,” she told news.com.au.

“Suicide was not on his mind at all, he just thought it was so dumb, because, he felt the results of it,” she said, referencing a close friend’s mental health struggles.

She said her younger brother had a “collection of sort of neurodivergent friends” who were very in tune with their feelings and supported each other in a unique way.

“He was really well adjusted,” she added.

His father told police that Sam had made “frequent comments” that staff “would frequently ignore his text, email and telephone messages” since making the move to Melbourne.

news.com.au sent a detailed list of questions to PGC and received a statement that the company would not be making any comment due to an active police investigation.

No action has been taken, and the WorkSafe investigation remains ongoing.