Grieving father Michael Garrels joins calls for senate inquiry into construction deaths

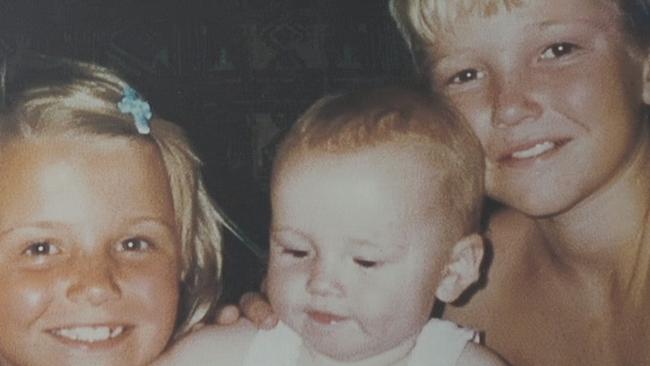

JASON Garrels had only been a tradesman for nine days when he died on the job. And it was a phone call that cost him his life.

IN FEBRUARY 2012, Jason Garrels was electrocuted at a central Queensland building site.

The 20-year-old tradesman had been on the job for only nine days when a switchboard he was carrying touched live wires, causing a tragedy that was entirely preventable.

His boss, Nathan Brian Day, should have switched off power to the entire street, but had failed to do so after being distracted by a phone call.

The young man was rushed to Clermont Hospital where his mother Lee worked as a nurse and was on shift, but he could not be saved.

Instead of owning up to his negligence, Mr Day, 31, tried to cover up what really happened by stripping the site’s main switchboard, blaming Mr Garrels for the incident and attempting to influence witnesses.

After a six year battle for justice, Mr Day finally pleaded guilty to manslaughter and perjury earlier this month.

He was jailed for a maximum seven years, and will be eligible for parole in March 2020.

Jason’s heartbroken father Michael Garrels told news.com.au the sentence had set an Australian precedent, and that individuals needed to be held responsible for workplace deaths.

He has thrown his support behind a Senate Reference Inquiry into construction deaths, which

news.com.au understands has recently been approved, with submissions possibly due in September.

Mr Garrels has called on the government to do more to address the “broken system”.

“There’s no joy in it — not one little bit of joy,” he said of Mr Day’s sentencing.

“If you add up all the deaths in industry over the past 40-odd years workplace legislation has been in place in this country, there would be a small city of people killed at work.

“That tells you something is wrong. It’s a broken system.”

Mr Garrels said he immediately knew that his son’s death was suspicious as he had previously worked as a linesman.

One brother who is a police officer and another who is a former cop also helped him to uncover the truth of what occurred the day Jason died.

Mr Garrels believes if it wasn’t for those factors, the man responsible for his son’s death would probably not have been jailed — and he said there were countless examples of perpetrators dodging justice across the country in various industries.

“If someone dies by oversight, personally I could have come to the point where I could forgive them, because everybody is guilty of oversight. But when it’s systematic … we’ve got to grab these people and make examples of them,” he said,

“I’ve got nothing against people trying to make money but you should put yourself at risk, not anybody else.”

Mr Garrels said when an Australian died at work, the current system imposed fines — which were usually covered by a company’s insurance — instead of holding individuals criminally responsible.

“When a loved one dies in industry, all you get is so much window dressing,” he said.

“It turns out to be subsidised in one form or another in so many cases — if you’re a bigger company that is quite established, you generally have enough money to have insurance for deaths.

“To me it’s like if a car ran up a footpath and ran over pedestrians, and we say ‘let’s charge the car and leave it at that’. But that’s what happens in worksites.”

Mr Garrels said workplace deaths should be investigated by authorities in the same manner homicides are.

“Police have to be more involved because police do their own investigations but it’s generally a very cursory one,” he said.

“I think they may be guilty of going in with the mindset that this is just a terrible accident.

“But an accident to me is when the person who is dead made all the decisions that led to their death, and too often that’s not the case.”

Mr Garrels said the impact of a workplace death was monumental.

“It leads to a high percentage of people losing their homes and marriages, it leads to mental illness — there’s a plethora of things that happen,” he said.

“I know we sold our house in Clermont and moved away because we couldn’t bear to be there.

“We loved Clermont, but it was just so, so confronting.”

Mr Garrels said a Senate Reference Inquiry would save young lives.

“Every death is avoidable. We can do far, far better to make sure there aren’t people out there who are prepared to put other people at risk for a few dollars,” he said.

“In our case, justice for Jason is also about making sure it doesn’t happen again.”

According to Safe Work Australia, 27 Australians have already been killed at work in 2018.

Three of those deaths occurred in the agriculture, forestry and fishing industries, six in construction and 13 in transport, postal and warehousing.

One electricity, gas, water and waste services worker has been killed, along with one wholesale trade worker, one administrative and support services worker, one manufacturer and one information media and telecommunications worker.

Earlier this month, news.com.au spoke with grieving NSW mum Kay Catanzariti, who has

also been tirelessly campaigning for the senate inquiry.

Her son Ben was killed in July 2012 aged 21 by a falling concrete pouring boom at a construction site in Canberra.

Ms Catanzariti said she had demanded an inquiry in an effort to save young lives, because: “Nothing is being done, and accidents are still happening.”