Lies, rot, ‘suicide’: The horror franchise stories

EVERYDAY Australians think this is the path to financial success and freedom from the office grind. But it’s actually ruining lives.

THE horrible underbelly of the franchising industry — the business model that brings us successful names such as McDonald’s and Jim’s Mowing — is being exposed once again.

The Senate is undertaking an inquiry and reading the submissions people have sent in is absolutely heartbreaking.

“Being a franchisee has destroyed the lives of myself, my family and caused severe financial distress at 70 years of age,” one person writes in. “I am … now working to try and keep the family home and repay significant loans incurred in relation to the franchise business.”

Meanwhile, franchisees of Oporto and Red Rooster stores say they are “on the verge of bankruptcy” due to the parent company’s unfair business practices.

The franchising industry is a huge part of the economy, a huge employer, and it makes some franchisees very rich. Some franchise companies — like McDonalds — are run so smoothly you almost never hear a complaint. But hidden deep inside it lives are being ruined, with lies, rot and talk of suicide.

LIES

Stories of franchises ruining someone’s life almost always include the claim they were lied to. Like the story of Faheem Mirza.

Mr Mirza is a certified practising accountant and also a chartered accountant. His child requires full-time NDIS support, so he was looking for a way to have a business he didn’t have to work in full-time.

He did some research and eventually became a franchisee when he bought a Muffin Break franchise. Mr Mirza claims he was informed the cost of labour to run the store would be between 21 to 30 per cent of sales. The franchising company denies this.

“No actual store data was made available prior to the actual commencement of the store operations,” wrote Mr Mirza in his submission to the Senate inquiry. “Once the operations started in June 2016, the labour costs were much higher than anticipated.”

Although sales were going well, Mr Mirza concluded that running the Muffin Break above board and legally was going to mean losing a lot of money.

Foodco, the franchising company that owns the Muffin Break brand, suggested he and his wife work up to seven days a week in the cafe without drawing any wages, Mr Mirza claimed, adding: “They told me to consider underpaying staff.”

There is no external evidence to support his claims about the cost of labour nor Foodco asking him to underpay staff. Foodco denies the claims, leaving us unsure whom to believe.

“We strongly refute the false allegations made by Mr Mirza,” said a Foodco spokesperson. “Our success is entirely underpinned by the success of our franchisees and we are committed to high levels of transparency.”

Mr Mirza tried to get his money back, but eventually discovered franchisees don’t have easy legal avenues at their disposal and “lost the entire investment and am now burdened with debt”.

Mr Mirza joins a long list of franchisees who say they were lied to. Should we pay attention? After all, if you lose everything, you are looking for anyone to blame but yourself. There is lots of information out there on franchising if you look, and franchisees often do too little research. Meanwhile, not every franchisee goes broke — some make a fortune.

So is this lying epidemic real? It is impossible to tell, but now we are discovering how dodgy some financial advisers can be, why would we expect all franchise companies to behave perfectly all the time? After all, they are selling a very high value product. Selling a franchise makes the franchising company money in many ways — not just the upfront payment.

For example, a common complaint among franchisees is that the franchising companies get suppliers to pay money to the franchising company in return for making franchisees buy their products, which are not always great value.

For example, one franchisee at a fast food chain claims he was forced to purchase bottled Mount Franklin water from the approved supplier for $18 a case, while he same case was on sale at the IGA up the road for $11.

ROT

Trent Scaf wanted to get out of his fly-in, fly-out job on the oil rigs so he could spend more time with his two little kids. He and his wife Abi believed in small business, the community and supporting local farmers, so it made sense to get involved with Aussie Farmers Direct.

“Their ethos seemed to represent our values too — fresh produce, higher standards and a convenient, sustainable food service,” wrote Trent and Abi in their submission to the Senate inquiry.

Trent and Abi bought four Aussie Farmers Direct franchises, a decision that would cost them dearly.

“Sadly, over time, we discovered many things are not the way they were originally presented to us. The fresh produce in 2016 in WA was around 50 per cent from wholesalers and not local farmers as we and our customers were led to believe. This led to mouldy, rotten produce being supplied, persistent out of stockages and even off-meat was an ongoing issue.”

Abi and Trent struggled to get a meeting with the franchising company to talk through their problems.

“It took three months for Aussie Farmers Direct to actually commit to a meeting that they then requested to leave from early in order to return to Melbourne for an AFL Grand Final party,” wrote Trent and Abi.

But the rot at Aussie Farmers Direct was not just on the produce. While Trent and Abi took $30,000 in wages in two years, the company itself was dying from the inside out.

Finally, they got the company to promise that if they could not sell the businesses very soon, it would pay them enough to clear their business loan. That promise would never be kept, because in March this year Aussie Farmers Direct went broke, leaving Trent and Abi stranded.

TALK OF SUICIDE

Elke Meyer is a former police officer who worked until 2016 as a contractor at Retail Food Group, the company that owns Gloria Jean’s, collecting moneys owed from the coffee chain franchisees.

She describes meeting a sequence of stressed and indebted franchisees that seemed to get worse and worse.

“I became deeply concerned with the situation among an increasing group of franchisees when a female franchisee of a Gloria Jeans franchise advised me she and her husband and two young sons had sat on the floor the night before and hugged, and her husband had decided to take his own life so they could get the life insurance and pay out their debt to [Retail Food Group],” wrote Ms Meyer in her submission to the Senate inquiry. “There was an overwhelming sense of hopelessness among a lot of the franchisees I dealt with, but this instance was the most extreme.” (The man did not take his own life in the end.)

A Retail Food Group spokesperson pointed out that running a small business is tough, but the company’s franchises last longer than the average small business.

“Indeed, latest Australian Bureau of Statistics data indicates that new small businesses suffered from a failure rate of circa 45% during [the 2014 to 2017 financial years]. By way of context, average franchisee tenure within [Retail food group’s] brand systems well exceeds the timeframe contemplated above,” the spokesperson said.

You can never say unhappy franchisees are purely the fault of the franchising company. Nevertheless, the decision to buy a franchise seems, statistically, to be an unhappy one.

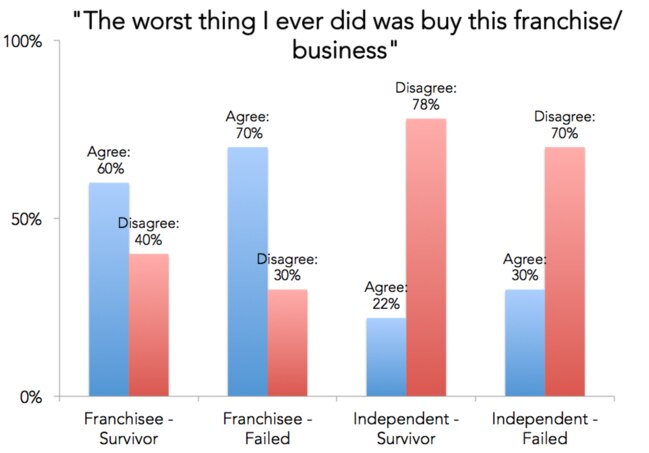

A big Australian study asked people whose franchise failed if buying it was “the worst thing I ever did,” and 70 per cent of them agreed. But what’s really shocking is that when they put that same question to people who had an operating franchise that hadn’t gone broke, 60 per cent of them agreed as well.

The study asked the same question to operators of independent businesses, and they felt much more positive about their choices, as you can see in this next graph.

The people quoted in this story — who complained to a Senate enquiry — are not a representative sample of all the franchisees in the world. There are many, many happy ones. But the chart above suggests there might not be as many as you’d think.

There seems to be something different about operating as a franchise — perhaps expectations of success are raised because you paid for a business model, or perhaps the rules and payments seem to choke your business at times — that makes it feel more frustrating. Franchisees fail less often than independent businesses, but they also normally have higher debt, so when they fail, the owners are often worse off.

One thing I know for sure now is that personally, I plan to never buy a franchise.

If you or someone you know needs help, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14.

Jason Murphy is an economist. He runs the blog Thomas the Think Engine.