‘Worst on record’: One thing that could solve Australia’s rental crisis

With Australia’s housing and rental crisis set to get worse before getting better, there’s one quick fix that can government can do right now.

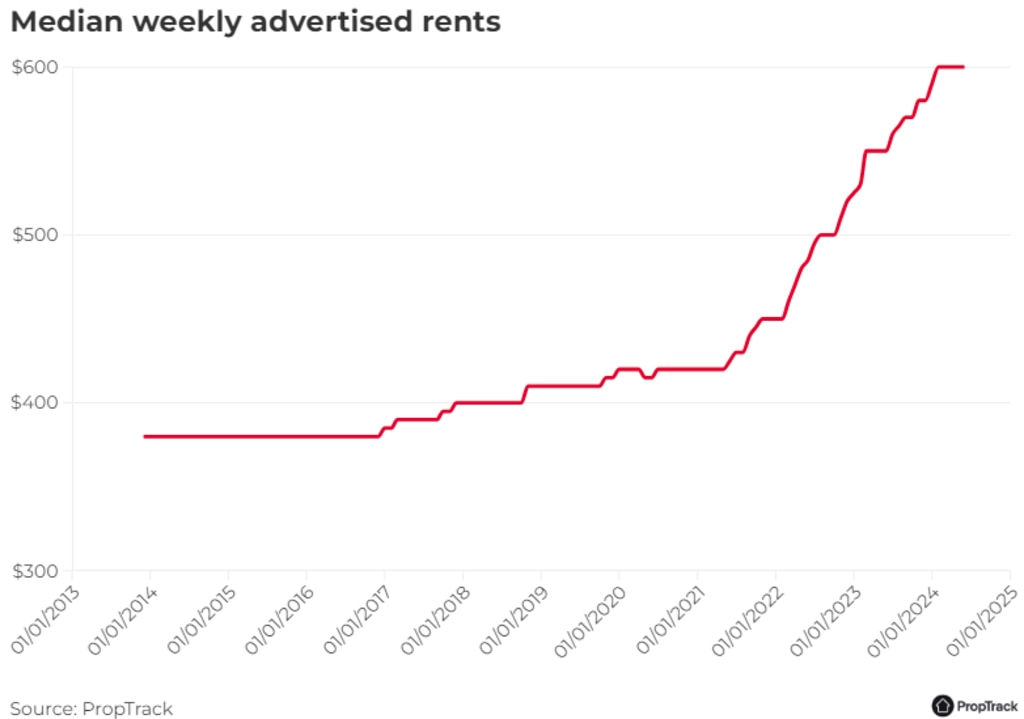

Australian renters received some positive news with rental growth easing in June and the rental vacancy rate rising for four consecutive months.

“Australia’s rental vacancy rate has now eased for four consecutive months, rising from a record low of 1.09 per cent in February to 1.42 per cent in June,” reported PropTrack

senior economist Anne Flaherty.

Separate data from other property firms also reported softening rental growth alongside rising vacancy rates.

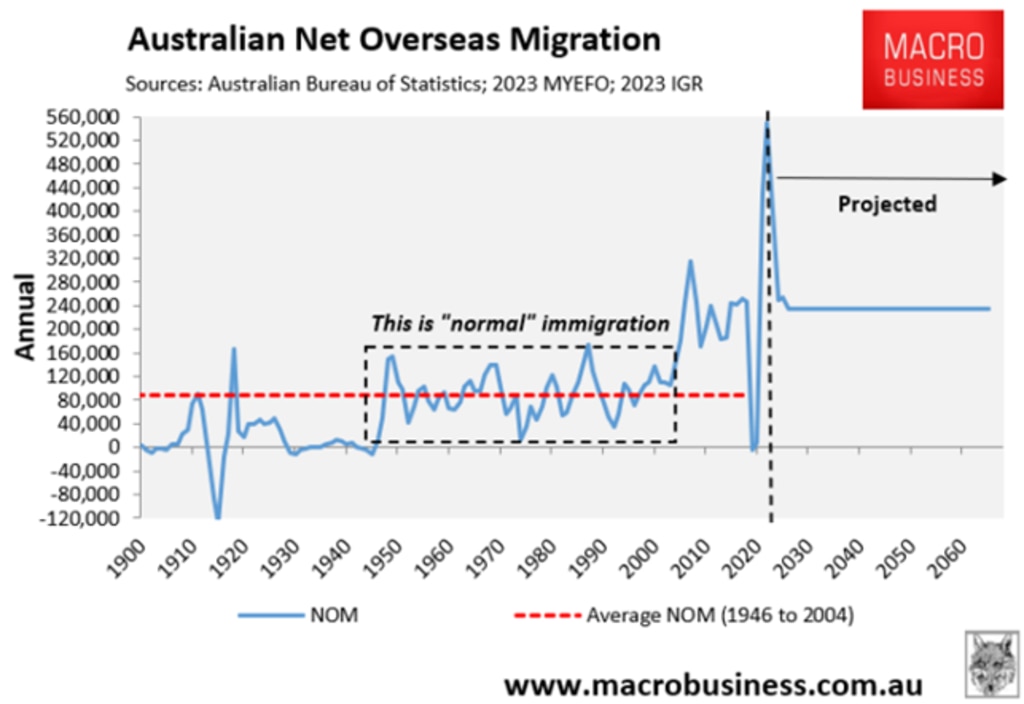

The easing of rental growth comes amid an easing of net overseas migration, which peaked in the September quarter of 2023 at a record annual rate of 564,500.

This slowing in net overseas migration is having the greatest impact on the unit markets of the three largest capital cities, which are recording sharper moderations in rental growth.

Rents also appear to be hitting an affordability ceiling after rising by around 40 per cent since the beginning of the pandemic.

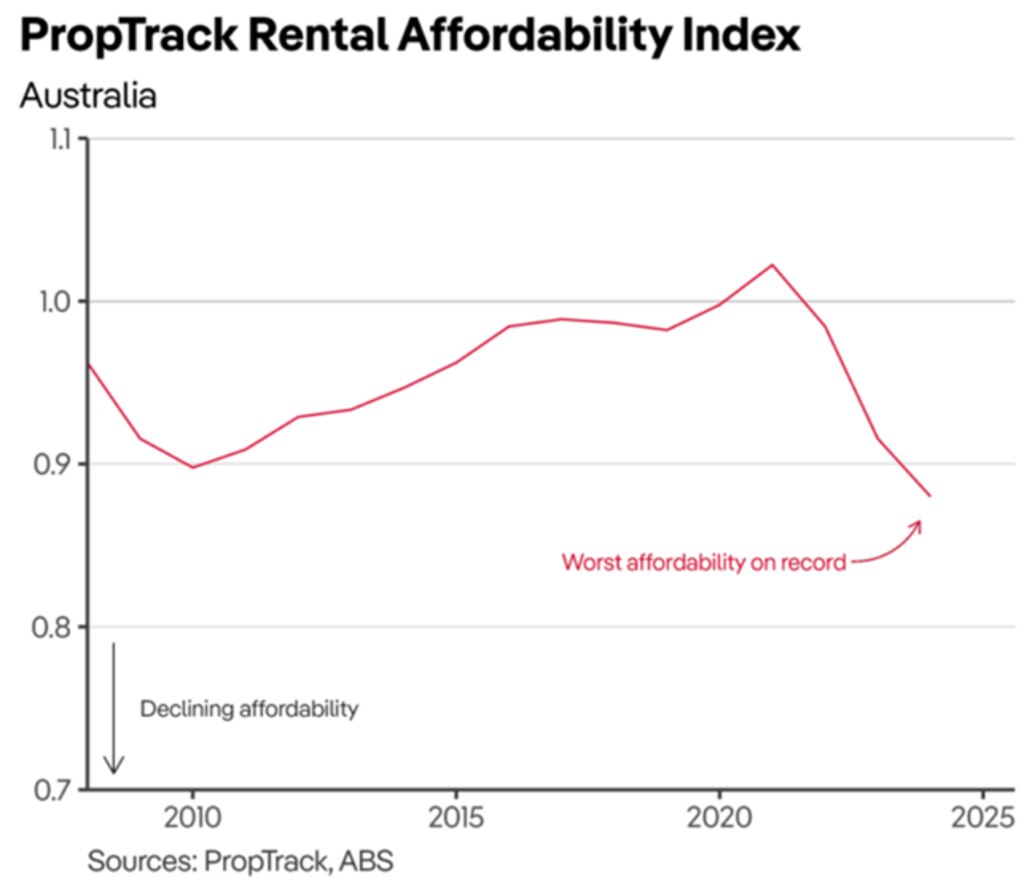

PropTrack’s Rental Affordability Report found that “Australia’s rental affordability is at its worst level on record”, with households earning the median income of $111,000 only being able to afford to rent the smallest share of properties since 2008 when records began.

Unlike mortgages, rents cannot be leveraged. This means that rental growth is more closely tied to household incomes, limiting its potential increase.

Rental situation remains precarious

Despite the moderation in rents and the increase in vacancy rates seen in recent months, the situation facing tenants remains precarious.

According to PropTrack, the national vacancy rate remained 43 per cent below pre-pandemic levels in June.

It all comes down to supply and demand.

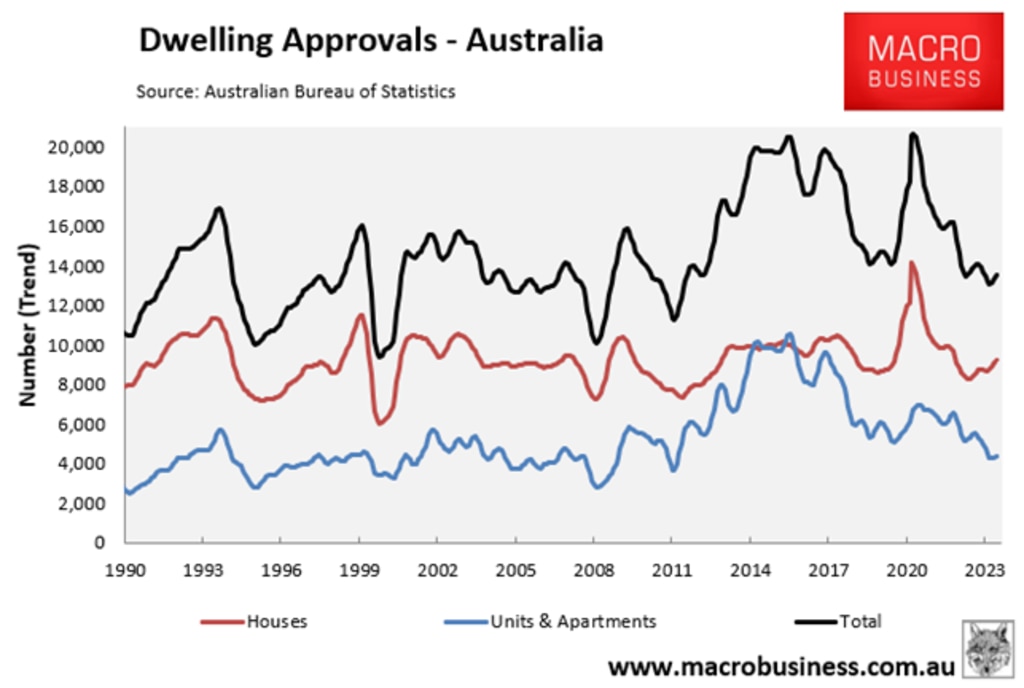

The latest data on dwelling approvals from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) showed that only 13,500 homes were approved for construction in May in trend terms.

This level of approvals is 6,500 (32.5 per cent) below the monthly run rate of 20,000 required to meet the federal government’s target of building 1.2 million homes over five years.

Annual approval rates were no better, with only 163,800 homes approved for construction in the year to May, 76,200 (32 per cent) below Labor’s 240,000 housing target.

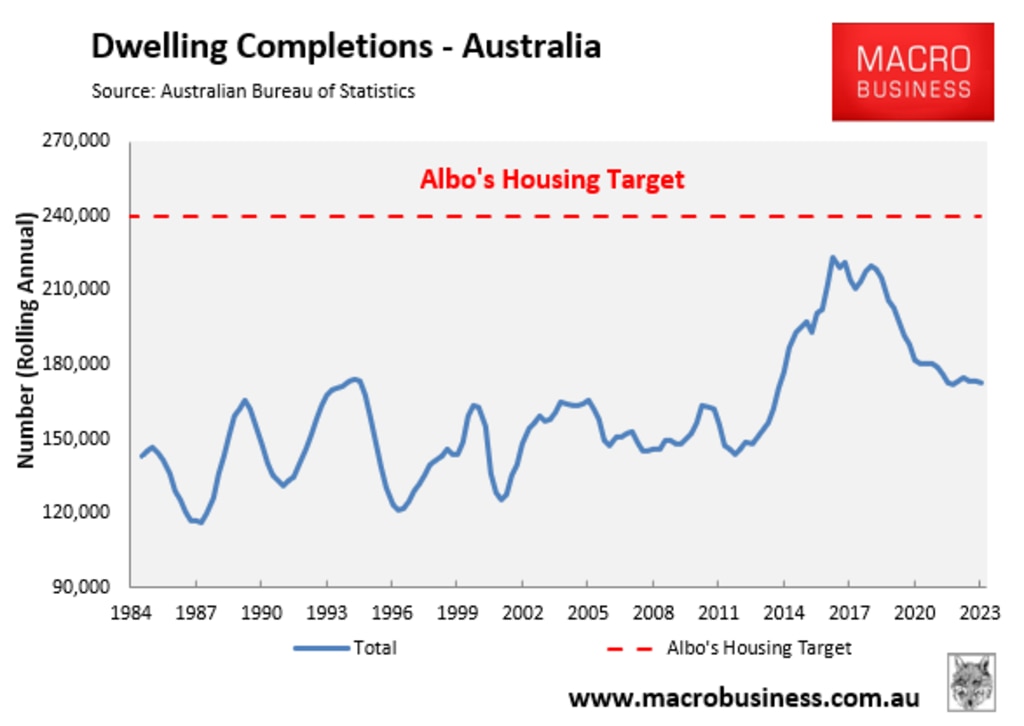

It is important to point out that the Albanese government’s target of building 240,000 homes annually has never been achieved before.

The current record level for housing construction over a 12-month period was 223,600 in 2017, which was 7 per cent below Labor’s target level of 240,000 homes.

This level of construction was achieved when the official cash rate was only 1.5 per cent, versus 4.35 per cent currently.

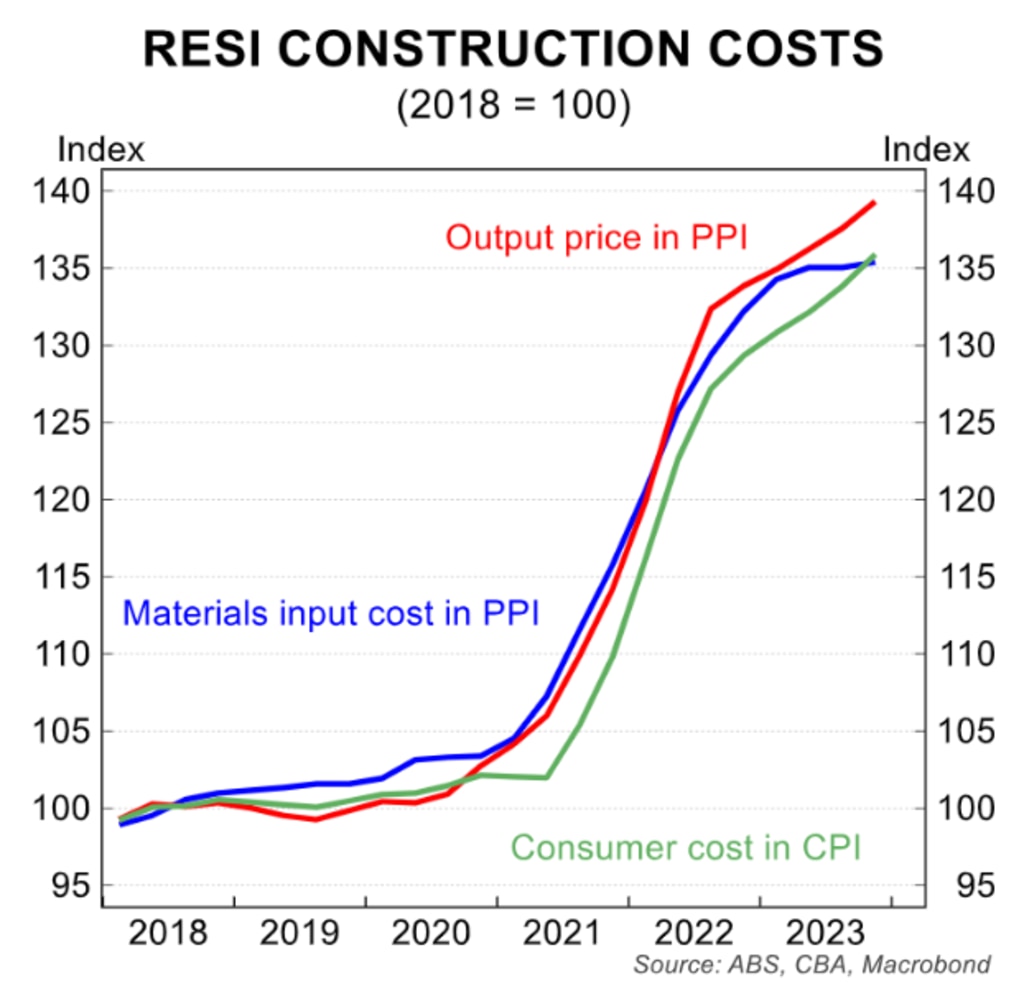

The 2017 record level of construction was also achieved when construction costs were some 40 per cent lower than they are currently.

In 2017, the residential building industry also did not compete for scarce labour and materials against government’s big build infrastructure projects.

Finally, the latest insolvency data from the Australian Securities and Investments Commission shows that nearly 3,000 construction firms went bust in the 2023-24 financial year, suggesting that productive capacity has been reduced in the home building industry.

In short, macroeconomic conditions are likely to remain unconducive to building homes, and construction rates are likely to remain suppressed for the foreseeable future.

Meanwhile, ongoing strong population growth (immigration) will continue to make life difficult for Australian renters by worsening the imbalance between demand and supply.

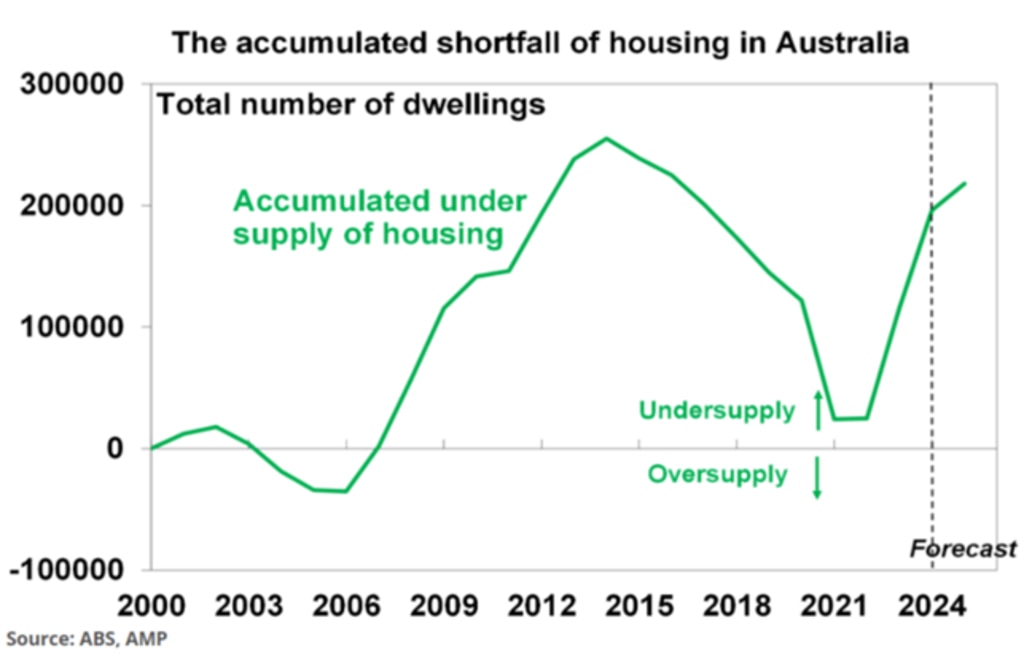

The following chart from AMP chief economist Shane Oliver shows that Australia’s structural housing shortage began when net overseas migration was more than doubled in the mid-2000s:

This shortage was almost eradicated during the pandemic when net overseas migration briefly turned negative.

However, the housing shortage worsened once again after the international border reopened and nearly one million net migrants arrived over two calendar years.

Shane Oliver estimates that Australia’s structural housing shortage has grown to around 200,000 dwellings, which will continue to worsen as population via net overseas migration

grows faster than new dwellings can be supplied.

However, Oliver stressed that his shortage estimate is conservative.

“If the decline in the average number of people per household seen in the last few years is sustained then the accumulated shortfall could be around 300,000 dwellings”, Oliver wrote

in June.

This “would be well above where we were before the unit building boom got underway around 2015,” he added. “The housing shortfall looks like it will get worse before it gets

better”

Cut Immigration or the rental crisis will become permanent

The reality of the situation is that the only genuine solution to Australia’s housing shortage and rental crisis is for the federal government to slash net overseas migration.

To eat into the accumulated housing shortage, net overseas migration must be reduced to

a level that is below the nation’s capacity to build housing and infrastructure.

However, the 2023 Intergenerational Report projected that net overseas migration will run at 235,000 per year into eternity, swelling the nation’s population to 40.5 million in just 39 years – equivalent to adding another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane to the current population of 27 million.

Such extreme immigration will guarantee that Australia remains in a permanent housing shortage, placing continuous upward pressure on rents.

Leith van Onselen is co-founder of MacroBusiness.com.au and Chief Economist at

the MB Fund and MB Super. Leith has previously worked at the Australian Treasury,

Victorian Treasury and Goldman Sachs.