Queensland has been declared the homelessness capital of Australia as housing crisis cripples the Sunshine State

One state is famed for its spectacular weather and enviable lifestyle, but the beauty masks a disturbing crisis.

Queensland has been given the undesirable title of the homelessness capital of Australia, with the Sunshine State at the “epicentre” of the country’s crippling housing crisis, support groups say.

A critical shortage of homes coupled with soaring demand has pushed up rental prices sharply, forcing many of the most vulnerable in the community into homelessness.

Stark signs of the extent of the crisis are visible across southeast Queensland, with tent cities popping up in Brisbane and on the Gold and Sunshine Coasts.

Some 40 people have been sheltering at the Pine Rivers Showgrounds in Brisbane’s north. Among them is Tracey Hind and her partner Stephen Ibeston.

The pair have been sleeping rough since February when skyrocketing rent increases forced them from their home.

Ms Hind, 58, and Mr Ibeston, 72, told The Courier-Mail last month that they have been sleeping in a tent at the showgrounds ever since, while they desperately try to save money to buy a camper van.

Those most in need of support are languishing on social housing waitlists for almost two-and-a-half years, a year longer than pre-Covid levels, the Queensland Council of Social Services said.

And a growing number of children are bearing the brunt of the housing and cost-of-living crises.

QCOSS chief executive Aimee McVeigh said data showed a third of all applications for housing help are from Queenslanders with children, up nine per cent since December alone.

The social housing wait list has also seen an increase in the number of single-parent applications, as well as couples with children.

“Queensland is absolutely at the epicentre of the housing crisis,” Ms McVeigh said.

“We have seen huge increases and ongoing increases in demand for social housing in the state, worsened by some really significant rent increases.”

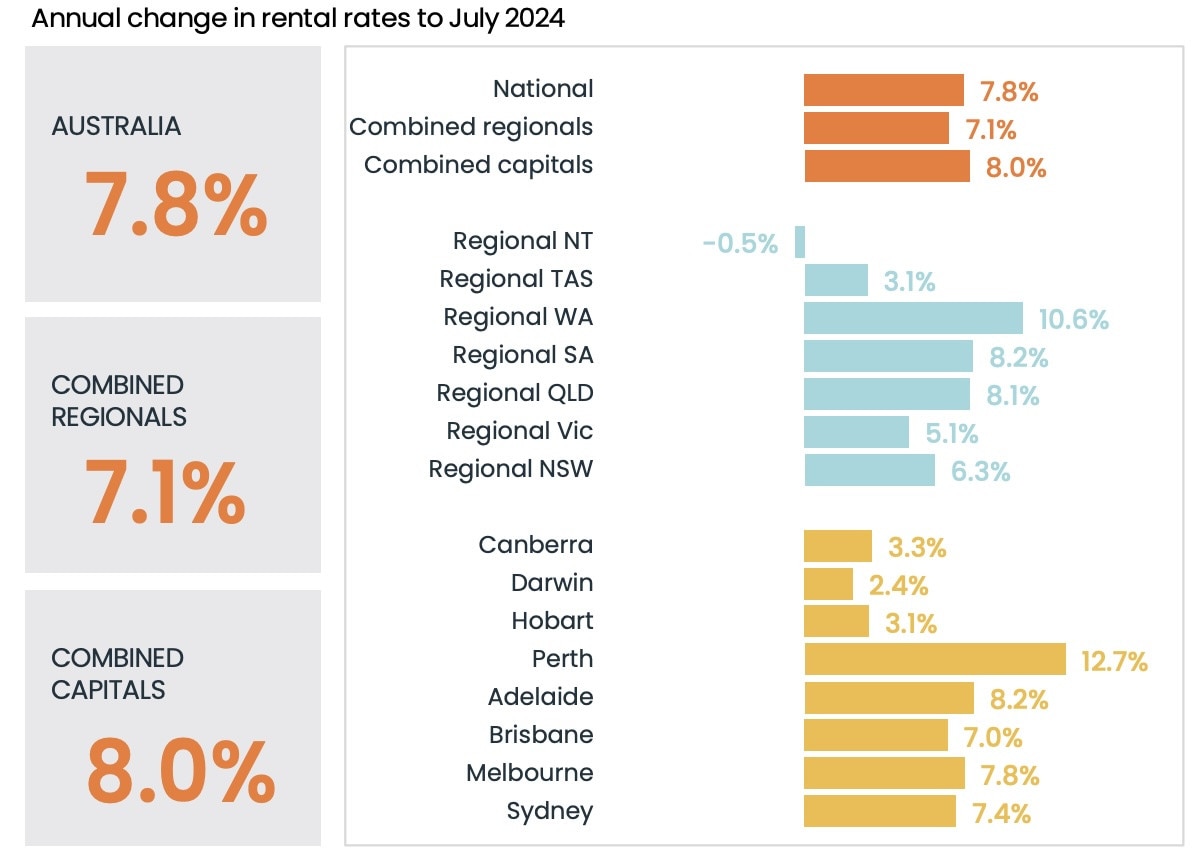

It’s not just in the southeast Queensland corner where people are struggling. Regional Queensland is becoming the most expensive non-metropolitan rental market in the country.

“If you were to take everyone on the social housing register and form a town, it would be Queensland’s fifth-biggest population centre.

“But we have commissioned independent research that shows the social housing register is just the tip of the iceberg. It’s a bit of a wobbly indicator of the need for support we’re seeing.

“In fact, the number of Queenslanders with housing needs is closer to 300,000. That’s roughly twice the size of the population of Cairns.”

A worsening affordability crisis

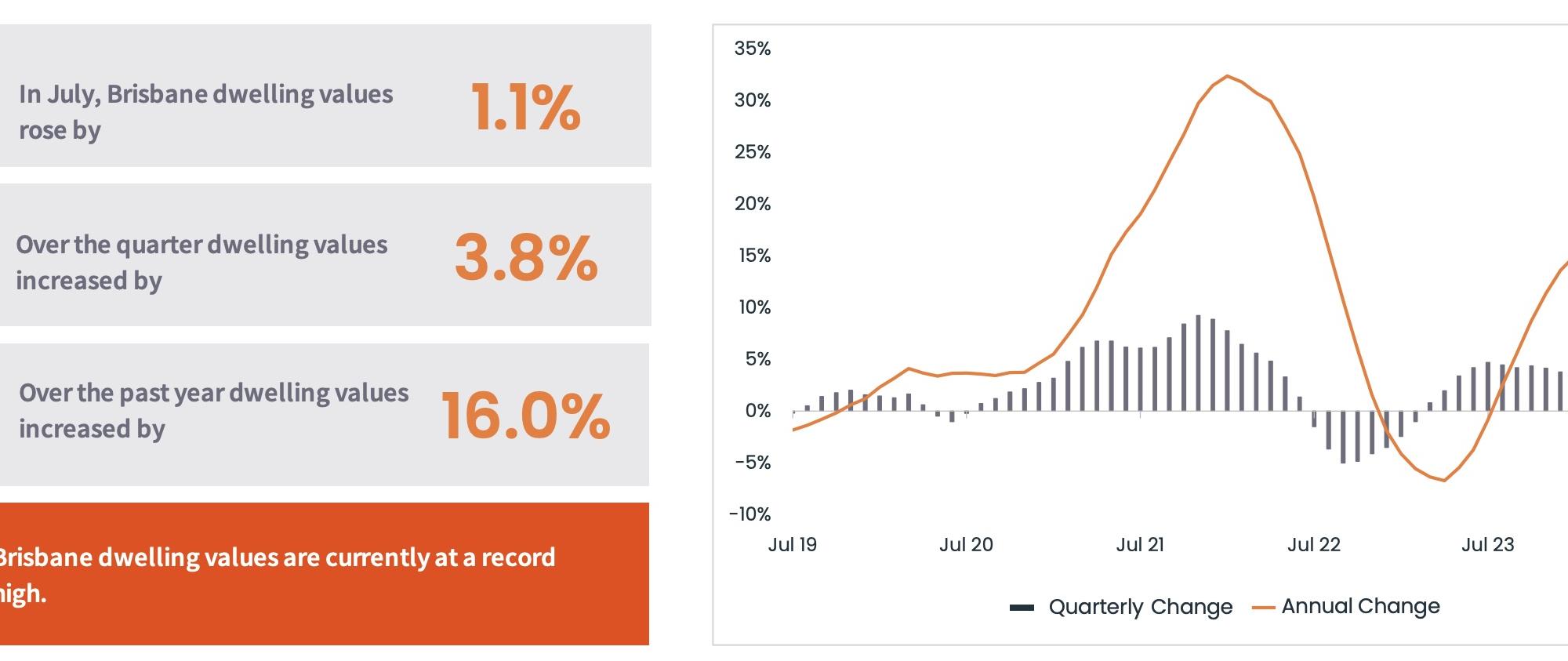

Home prices in Brisbane have surged by a staggering 65 per cent since the start of the Covid pandemic, which is close to double the capital city average.

Data released in June by research house CoreLogic revealed the Queensland capital has the second-most expensive housing market in the country.

Prices rose another 1.1 per cent in July and are now 16 per cent higher than this time a year ago. The median home value has hit a record high of $873,000 – higher than Melbourne’s median of $781,000.

Markets in regional Queensland have also been running hot, with values outside the southeast corner leaping by 11.9 per cent in the past 12 months.

Professor Hal Pawson from the City Futures Research Centre at UNSW Sydney said the scenario for Queensland renters has been particularly dire.

“Across the state, new tenancy rents are up by 45 per cent in just four years,” Professor Pawson wrote in analysis for The Conversation.

“Adjusted for inflation, that’s a 23 per cent increase in real terms, much more than the growth in incomes over that time. Without doubt, rising accommodation costs are inflicting financial pain on many in the Sunshine State.”

Brisbane’s rental vacancy rate - that is, the proportion of all leased homes currently available on the market - is just 1.1 per cent.

In January, polling by The Courier-Mail found two-thirds of Queenslanders are now struggling to pay their rent or meet mortgage repayments.

Meanwhile, analysis conducted by the City Futures Research Centre found the share of rentals that low-income Queensland holds can afford has crashed from 23 per cent in 2020 to just 10 per cent.

And examining the month of March, the research found a single person earning minimum wage or an elderly couple on the pension could afford just one per cent of available properties for lease.

“These conditions push some people into homelessness [and] with ‘tent cities’ appearing across Brisbane, the crisis looks to be deepening,” Professor Pawson said.

The root causes of the crisis

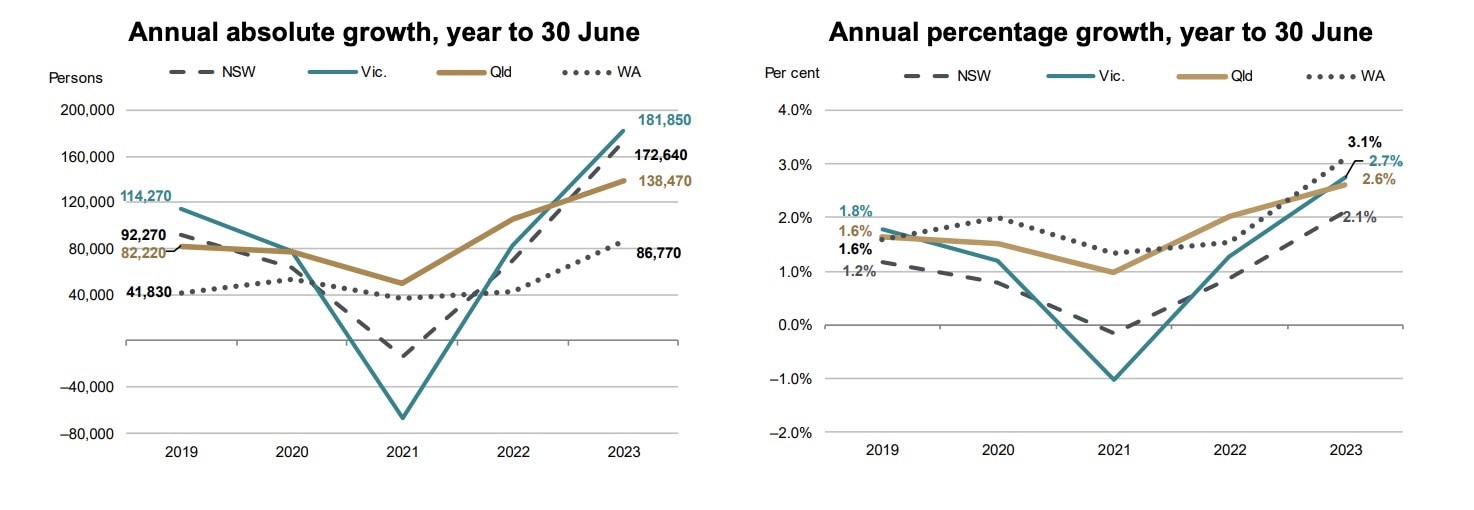

A major driver of the housing crisis has been record high population growth, with an additional 138,000 residents in the 2022-23 financial year.

Sixty per cent of that mammoth increase came from net overseas migration, while interstate flows of some 32,000 people from southern states.

Interstate migration has been particularly strong in the post-Covid era, with tough restrictions and rolling lockdowns in Melbourne prompting a number of people to relocate north.

But Professor Pawson said decades of inaction and complacency on the part of state and federal governments has also contributed to the crisis.

“Both … have been highly culpable,” he said. “And, given their complexity, the fundamental flaws of our housing system cannot be quickly solved, even if there is the political will to do so.”

However, there are dramatic signs of change in Queensland, he pointed out.

“Nowhere is this shift more striking than in the area of social housing – public or community housing for the lowest income earners.

“This is a sector in long-term decline across Australia. Investment has been minimal since the 1990s. By 2021, social housing was down to barely three per cent of all occupied dwellings in Queensland.”

Efforts to ease the pain

The State Government has eased entry restrictions on social housing, making it easier for those in need to get support, and committed to a new build program at a rate not seen since World War II.

Premier Steven Miles has pledged to boost the social housing pool by an extra 53,500 dwellings by 2046, which would expand stock by 73 per cent.

As well as constructing new homes, Queensland is buying existing properties – like empty and unneeded hotels and services apartment blocks – and converting them into social housing.

One of them, the old Menso Hotel in South Brisbane, began welcoming its first new residents in July after a refurbishment converted the former short-stay accommodation into 12 two-bedroom units and 48 studios.

It is the third inner-city hotel purchased by the Queensland Government so far, Housing Minister Meaghan Scanlon said.

“Our Homes for Queenslanders plan is pulling every lever possible, whether that’s buying former retirement villages, accommodation parks and hotels, building modular homes, and supporting the Federal Government’s Help to Buy shared equity scheme,” Ms Scanlon said.

Another component of the Homes for Queenslanders policy, a $350 million fund to support the accelerated development of new homes in under-utilised urban areas, received more than 220 applications in two weeks.

Of those, some 60 per cent of proposed projects already had development approval, meaning they could be brought forward, Ms Scanlan said.

Data released last month revealed homeless Queenslanders spent more than 270,000 nights in total in emergency accommodation over the past two-year period.

That marked a mammoth 792 per cent increase on the July 2022 to March 2024 period measured.

But this surge has been attributed to the government’s expansion of emergency accommodation, declaring earlier this year that anyone who needed it would be eligible.

Change is a long-term game

Building new dwellings or retrofitting existing properties to house those in need are not simple or quick tasks.

While Ms McVeigh commended the State Government’s efforts, she said more immediate policy reform is needed to ease the burden on people now, not in several years’ time.

“They have improved the laws for renters, however these haven’t gone far enough,” she said.

“They won’t address the key issues, which are security of tenure and affordability. What we do need to see is some real political bravery here, which would mean that we regulate the private rental market to how much prices can be increased by.”

Ms McVeigh believes progress at a federal level has been slow and lacks the “ambition we need”.

“We need an overarching policy direction that treats housing as a human right, with a goal to put a roof over the head of every Australian,” she said.

“We have a universal healthcare system and universal education, meaning every Australian has access. We’re not always perfect in the delivery of those services, but we have a cultural expectation that everyone should be able to access education and health services.

“We need to set that same expectation when it comes to housing because without a roof over your head, nothing else is really possible.”

And social services groups say the immediate need is significant – and growing larger by the day.

In its latest research, the charity Foodbank Queensland found 23 per cent of households across the state are “actively going hungry”, forced to eat less or skip meals entirely.

Some are going entire days without eating, the group’s chief executive Jess Watkinson said.

The number of Queenslanders facing food insecurity, an estimated one-in-five, is the equivalent of twice the population of the Gold Coast, Ms Watkinson said.

“The number one reason households in Australia struggle to meet their food needs is the cost-of-living crisis. We have all felt the impact of increased mortgage repayments and rent, and rising food, fuel, and home energy costs.

“We know that our country produces enough food to feed our population three times over – and Queensland provides one third of that produce.

“We must do better to ensure nutritious, culturally appropriate food reaches the dinner tables of everyone in our state.”

Eat Up Australia, another food charity providing free school lunches to kids who would otherwise go hungry has seen a 40 per cent increase in meals delivered in Queensland over the past year.

“The demand for our services is showing no signs of slowing down, which shows that children

are going to school hungry or without their lunch,” the group’s co-CEO Elise Cook said.

“We urge schools to get in touch, and for more funding to be provided as families continue to grapple with the rising cost of living.”

In the 2023-24 financial year along, Eat Up provided 963,000 free lunches to schoolchildren in need across the country.