A coronavirus-induced house price bust will hurt more vulnerable Australians than wealthy landlords, experts warn

If property prices collapse as a result of the coronavirus-induced economic crisis, vulnerable Aussies will suffer – not wealthy landlords.

If the Australian housing market tanks as a result of the coronavirus-induced economic crisis, it will worsen the inequality that rising prices helped to fuel, experts have warned.

Increasingly dire forecasts from economists paint a picture of significant losses in the back-end of 2020, as the consequences of COVID-19 worsen and government stimulus runs out.

But rather that deliver relief for Aussies battling with high rents or locked out of markets due to the long-term boom in prices, a collapse in house prices will hurt.

A trio of urban researchers say rising unemployment poses the biggest threat to housing market stability, with a major downturn likely unless the jobless rate recovers “rapidly”.

“Those who benefit most from a boom are not those who pay the price when it busts, and those harmed by the boom often become even more vulnerable during the bust,” Ilan Wiesel from the University of Melbourne, together with Liss Ralston and Wendy Stone from Swinburne University, wrote in an article for The Conversation.

Recent first homebuyers are those likely to be hit hardest in the event of a market bust, they wrote.

“We estimate 24,000 households are at very high risk because they took out large loans that might soon exceed their home value and also work in sectors with high job losses. Another 135,200 are at high risk and 121,000 are at moderate risk.”

And any price relief for renters as a result of changing market conditions is likely to be very short-lived, they warned.

“Many private renters hope a housing downturn will translate into lower rents and perhaps give them a chance to buy their first home in a more affordable market.

“However, in the longer run, the slowdown in housing construction will create supply shortages, leaving rental vacancies low and rents high.

“Many landlords, mostly ‘mum and dad’ investors, have taken large loans to finance their property investment. They will need to keep rents high to hold on to their investment properties.”

RELATED: Follow the latest coronavirus updates

The only good news for some renters is that lower prices might enable them to become homeowners after being locked out of the market during the boom years.

“These households could benefit from a coronavirus housing bust if the market then recovers. Even so, their gains will do little to change the overall trend of rising inequality made worse by the housing downturn.”

And a downturn is not only likely – it’s forecast to be sharp and sustained.

A GRIM OUTLOOK

The forecast for property prices in the coming year and beyond differs depending on who you ask, but all economists agree – there will be declines across the board.

CommSec, the financial advisory arm of the Commonwealth Bank, is expecting a 10 to 20 per cent plunge over the coming six months due to flat economic activity and rising unemployment.

On top of that, a collapse in foreign investment activity and international migration numbers will play a significant role, it said in a May report.

“The usual underlying demand pulse from net overseas migration has evaporated because the border is shut,” the CommSec report said.

“New lending is expected to contract, buyer expectations have adjusted downwards from exuberance to pessimism, rents are likely to fall, auction clearance rates are expected to remain weak and turnover will be lower than usual.

“The net result means that price declines are inevitable.”

RELATED: Scott Morrison’s ‘dud’ HomeBuilder scheme won’t save jobs

In April, UBS also forecast a 10 per cent drop in house prices over the coming year but warns the decline could be steeper “without direct policy support”.

The analysis was released before the government announced its HomeBuilder stimulus scheme, although experts in recent days have said they don’t believe it will have a significant impact on markets.

NAB released its outlook at the end of April, saying the extent of a property market downturn would depend on Australia’s economic recovery.

Assuming a ‘U-shaped’ recovery, its “severe downside scenario” expects a 20 per cent drop in housing values in 2020, followed by an 11.8 per cent fall in 2021, before a modest recovery of 2.5 per cent in 2022.

That recovery model factors in a lengthy recession – Australia officially entered recession last week after almost three decades of uninterrupted economic growth – as well as steadily rising unemployment.

But if the economic recovery is “V-shaped” – a more rapid return of brighter conditions and an easing of unemployment – then the property outlook is less dire.

In that scenario, NAB expects a 10 per cent fall in prices this year before a reversal of fortunes in 2021, with a 2.6 per cent rise in values.

“The severe downside assumes that you get a very significant reduction in global GDP, therefore the demand for Australian goods and services offshore and exports would fall, that would clearly drive unemployment up," NAB chief risk officer Shaun Dooley said.

"You would have the potential impact on house prices as a result of that, as the economy really struggles."

RELATED: End of home mortgage honeymoon will lead to market reckoning

BIG DECLINES AVOIDED – SO FAR

In the month of May, all capital cities except Adelaide, Hobart and Canberra saw a modest decline in median dwelling prices, with the national combined measure falling for the first time since June last year, CoreLogic data shows.

And Tim Lawless, head of research at CoreLogic, is more upbeat in his midterm outlook for property markets.

“Considering the weak economic conditions associated with the pandemic, a fall of less than half a per cent in housing values over the month shows the market has remained resilient to a material correction,” Mr Lawless said.

“With restrictive policies being progressively lifted or relaxed, the downwards trajectory of housing values could be milder than first expected.”

Across the capitals, Melbourne’s housing market posted the largest falls over the month, down 0.9 per cent in May, following a 0.3 per cent reduction in April.

Values were also down in May in Perth (-0.6 per cent), Sydney (-0.4 per cent), Brisbane (-0.1 per cent) and Darwin (-1.6 per cent) but rose in Adelaide (+0.4 per cent), Hobart (+0.8 per cent) and Canberra (+0.5 per cent).

“I’m feeling much more confident about market conditions than I was mid-March but we’re not of the woods yet – that would be my summary,” realestate.com.au chief economist Nerida Conisbee said.

“It comes back to the fact this is not a financial crisis. Interest rates remain very low and the banks are lending so if you have a job you are in quite a good situation to buy. That’s what’s propping up the market.”

But economists are worried that the looming end of government stimulus will have an impact on property prices.

It’s being referred to as the ‘September cliff’ – the point at which measures like JobKeeper and JobSeeker, rolled out to help Australians through the COVID-19 crisis, will wind up.

RELATED: Surprise outlook for Aussie property prices amid economic havoc

The government has indicated it won’t extend the programs past that point and is instead focusing on restarting the economy to get people back into work.

September is also roughly the time that major banks will wrap up their mortgage repayment pause, offered to Aussies impacted by COVID-19.

Martin North, principal of research firm Digital Finance Analytics, believes mortgage stress will spike after September, putting further pressure on consumer spending and confidence.

DFA’s monthly survey found 37.5 per cent of households were experiencing mortgage stress in May, Mr North said.

“This means 1.4 million households are experiencing cash flow issues (right now),” he said.

Mr North expects the number of households in mortgage stress to jump to 40.3 per cent after the September cliff.

Another factor likely to contribute to market falls is the ‘delayed hangover’ from the coronavirus crisis.

Dr James Brugler and Dr Jonathan Dark, economist from the University of Melbourne, said housing markets are slow to react to broader economic turmoil

“House prices usually take longer to reflect what is happening elsewhere in the economy for a number of reasons,” Dr Brugler and Dr Dark wrote for the university’s Pursuit magazine.

“Essentially, houses are harder to buy and sell than stocks and bonds, houses differ greatly from one to the next, and people value houses as more than just investments.”

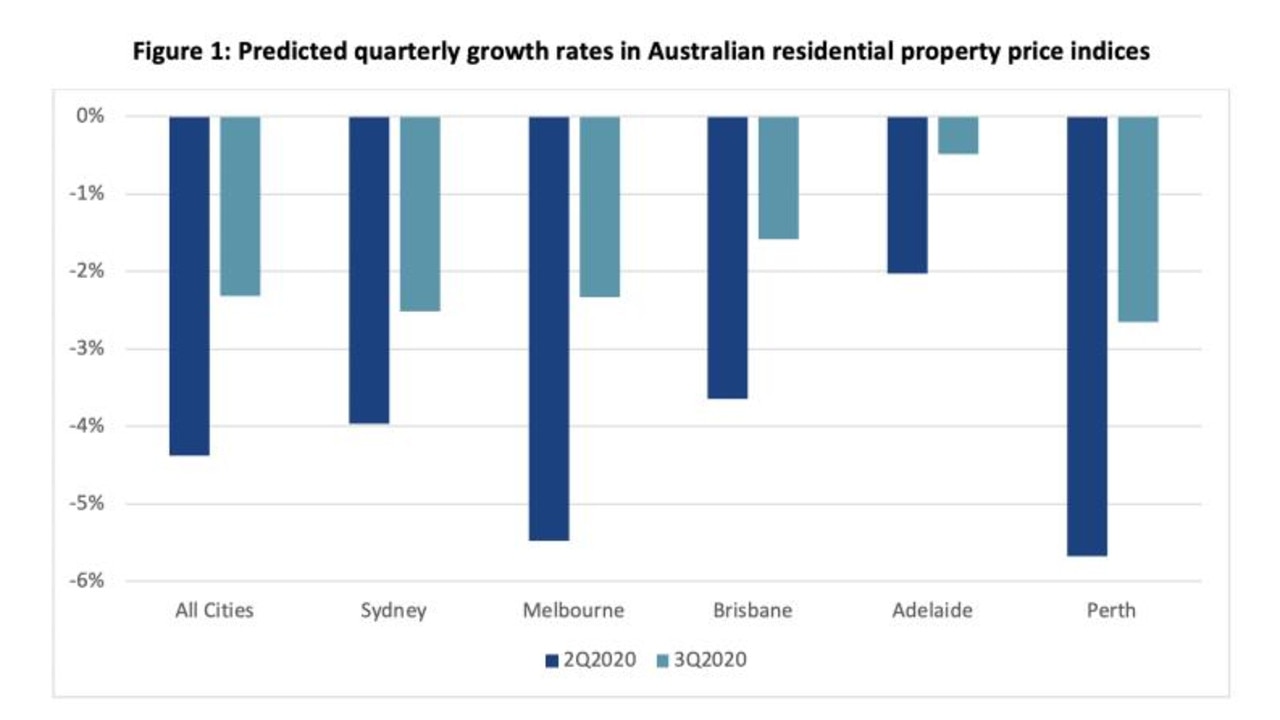

The pair modelled the short and midterm outlook for property prices and believe across all capital cities, a 4.4 per cent fall in the June quarter, followed by a 2.3 per cent drop in the September quarter, is likely.

“Sydney prices are predicted to fall by four per cent in the June quarter and about 2.5 per cent in the September quarter,” they wrote.

“Falls in prices in Brisbane and Adelaide are tipped to be less severe but in Melbourne and Perth, our models predict falls of around 5.5 per cent and 2.5 per cent in the June and September quarters, respectively.”

Improved housing affordability is crucial in order to reduce social and economic inequality and a downturn will lower house prices.

“But this (coming) downturn, when coupled with rising unemployment, will not deliver greater equality, especially if it’s followed by yet another boom,” Mr Wiesel, Ms Ralston and Ms Stone wrote in their analysis for The Conversation.

“Australia has flattened the curve of COVID-19 infections. To be successful in reducing inequality, we need to flatten the curve of both booms and busts in the housing market cycle.

“And only a thorough overhaul of national housing policy will achieve that.”