Is it time for the older generation to pay?

WHILE Australia’s young people struggle with higher house prices and university fees, one generation is laughing themselves all the way to the bank. Here’s why you’re getting ripped off.

THE wealth of older Australians is increasing but this is happening at the expense of younger people.

Households aged between 65 and 74 today are $200,000 more wealthy than households of that age eight years ago, despite experiencing a global financial crisis during that time. Meanwhile the wealth of households aged 25 to 34 has gone backwards, according to the report The Wealth of Generationsby independent think-tank the Grattan Institute.

It is no surprise that the housing boom has helped older Australians to become richer, while those who did not own property before 1995, seem to have missed out on huge windfall profits.

But rising property prices do not tell the whole story.

Incomes for older Australians also grew at a faster rate than young people, and this allowed them to save more.

Despite this rise in income, older Australians also paid less tax. Why?

The report says superannuation tax arrangements for older people could be playing a part. This is because people over 60 years old can reduce their income tax by up to $5000 a year via super tax concessions, and they can also use the Seniors and Pensioners Tax Offset to reduce their tax payable by up to $1600. This is regardless of whether they are actually retired.

Grattan Institute chief executive officer John Daley told news.com.au in August that these “outrageous” perks for older people were just a couple of measures that could be pulled back in order to balance the budget.

“Young Australians should be furious about this,” Mr Daley said at the time.

The report into the wealth of Australians also identified that older generations get a lot more from the country’s tax and welfare system, compared to younger people.

“A household headed by someone over 65 today receives $4400 more in real terms in welfare benefits each year than did the equivalent household 20 years ago,” the report notes. Most of this increase is due to a higher age pension.

The most dramatic increase to the pension happened between 2003/04 and 2009/10, when a 10 per cent increase to the base rate was introduced in 2009. A further 1.7 per cent increase was granted in 2010 to compensate for the introduction of the carbon tax and this was not withdrawn when the tax was axed. There were also changes to the pension asset test in 2006.

To make matters worse, pension increases have so far been financed through budget deficits rather than by increasing taxes or reducing benefits for other age groups.

Younger generations have so far been able to afford to finance the retirement of older generations, while also improving their own living standards, because incomes have almost doubled over the past 30 years.

But this trend looks unlikely to continue over the next 25 years because of the ageing population, significant increases in house prices relative to earnings, increasing government assistance for older Australians and budget deficits.

Growing deficits mean younger households may have to pay substantially higher taxes in the future, or reduce the benefits and services they provide.

“Younger households could face an extra $10,000 tax burden associated with each year of growing debt between 2010 and 2014,” the report states.

There are already signs of a fall in the fortunes of younger generations in both the US and UK where recession has disproportionately affected the young.

In the US, where income growth has been stagnant for more than a decade, wages have not improved for those aged 25 to 34 years old compared to what they earned in 1965. In contrast, those aged 55-64 earn about 40 per cent more.

“The experiences in these countries demonstrates how lower growth ... can depress earnings for an extended period. For those in their formative years in the workforce, the result is a significant hit to lifetime earnings,” the report states.

Unfortunately economic growth over the next few decades is likely to be much slower for all developed economies, including Australia. This could reduce the improvement in living standards and if wages do not grow much then capital gains, particularly from one-off increases in house prices for example, may see the older generation having more wealth than their children.

This would place more importance on parents providing their children with a large inheritance, with those lucky enough to receive a payout, eventually able to become more wealthy than their parents. However, relying on the inheritance model means the wealth would be much less equally shared in the community.

The problem is that inheritances tend to go to those who are older than average and already wealthy. “The wealthiest 20 per cent of Australians are four times more likely to receive a sizeable inheritance than is the median Australian,” the report found.

It also means that the vast bulk of wealth would be inherited by people when they are aged over 55, which means they will live more of their life with less money.

The report notes that older Australians are right to point out that they have paid taxes over their lifetime and are entitled to support in retirement. Older Australians have always paid less tax than they receive in benefits, while people of other age groups are “net contributors” to the budget. However, the transfer of wealth from younger to older generations has become so large that it may not be affordable as the population ages.

“In the past, each generation took out more from the budget over its lifetime than it put in. This part of the generational bargain was sustainable when incomes rose quickly, as they did for 70 years,” the report states.

But now “there are concerns that the current policy settings will lead to younger generations putting considerably more into the system than they take out over their lifetimes”.

What makes timely action even more important is that if government expenditures on health, pensions and super concessions are ultimately cut because budgets cannot sustain them, then younger Australians will be even more disadvantaged.

“Younger generations, on the wrong side of the drawbridge after the policies change, lose because they pay for these benefits for others but do not receive them themselves.”

Whether the younger generation is ultimately worse off than its parents will depend on policy change, the state of government finances and economic growth.

The Gattan Institute’s next report will focus on how different generations and budget outcomes could be affected by policies that more tightly target the age pension, asset taxation (particularly for land), and super tax concessions. These areas have been identified as some of the most attractive opportunities for budget repair.

Much of this could ultimately lie in the hands of older Australians, who form a significant voting block. According to the report, in the 2013 federal election, almost half of people enrolled to vote were 50 and over.

“Many undoubtedly care about the welfare of the next generation. Older voters may be persuaded that change is necessary if the dividend for younger Australians is clear.”

Mr Daley said the reforms would fall most on those who had benefited most from property windfalls and government largesse, and who had paid lower taxes while deficits accumulated.

“We shouldn’t delay, or a younger generation may be even worse off, as they miss out on benefits their parents enjoyed,” he said.

“The huge challenge for governments and the nation is to introduce policies that ensure we keep a vital part of the generational bargain: rising living standards for every generation.”

YOUNGER GENERATION

• In 2011/12, the average household was $80,000 richer than a household of that age eight years earlier. Those aged 25 to 34 on average went backwards in real terms.

• Are less likely to own property than their parents. An increasing proportion of those born after 1970 will never get on the property ladder.

• Many members of the generation born after 1965 missed out on increasing their wealth as house prices boomed from the mid 1990s.

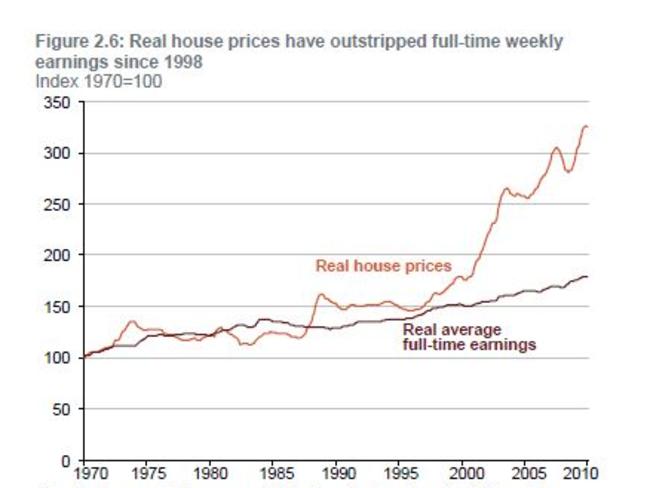

• Between 1995 and 2012, real house prices increased by 4.3 per cent a year, much faster than the growth in full-time earnings.

• Alongside rising prices, increasing education debts may be discouraging younger households from taking on mortgages to purchase a home. However, the impact of HECS debt on overall wealth was relatively small.

• While today’s 34-55 year olds own houses that are worth more, they had to borrow more to acquire them.

• They do own more other financial assets such as bank deposits and shares compared to their predecessors. Compulsory super should further boost their lifetime savings.

• Overall people are saving more of their income, this has increased from 0.4 per cent of after-tax income in 2003, to 10 per cent in 2013. Young households income increased at a lower rate, but they still managed to increase their savings by containing their spending, while older households saved more because their incomes rose faster. Those aged 55-64 increased what they spent by more than any other age group. At the same time their savings increased the most, because their incomes grew even faster.

• Less than a third of those responding to a survey considered that their lives would be better than those of their parents. “People today who are both young and poor are probably the most financially vulnerable group in society”.

OLDER GENERATION

• In 2011/12, the average 55-64 year old household was $173,000 richer in real terms than eight years earlier. The average 65-74 year old household was $215,000 better off over the same period.

• Property wealth increased the most for 65 to 74 year olds, by $110,000. For those over 75 it increased by $90,000.

• In 2003/04, households aged over 65, held about 26 per cent of the country’s total wealth. Just eight years later, this had increased by four per cent, to about 30 per cent.

• All households paid more tax in real dollar terms than 20 years ago, except for households over 65 years of age, whose income tax bill declined, despite strong growth in income over the last decade.

• However, all age groups paid more indirect taxes, partly due to the introduction of the GST in 2000.

• Both Treasury and the Productivity Commission forecast that governments will spend more on health in real terms over the decades to come as a result of an ageing population. But all age groups have contributed to the rising cost of health over the past 20 years, with government spending per person increasing by about 3.7 per cent a year.

• Analysis from Australia and abroad suggest that older households generally maintain (and even increase) their wealth in retirement.

• There have been attempts to contain growth in spending on pensions by both the Rudd and Abbott governments, including lifting the qualifying age for the pension, though not all of them have been passed in parliament.