Madman on the money: How Australian pioneer John Macarthur died in obscurity after being declared a lunatic

HE founded Australia’s wool industry and became the face of the $2 note. But John Macarthur died a tragic death, declared a lunatic and shunned by society.

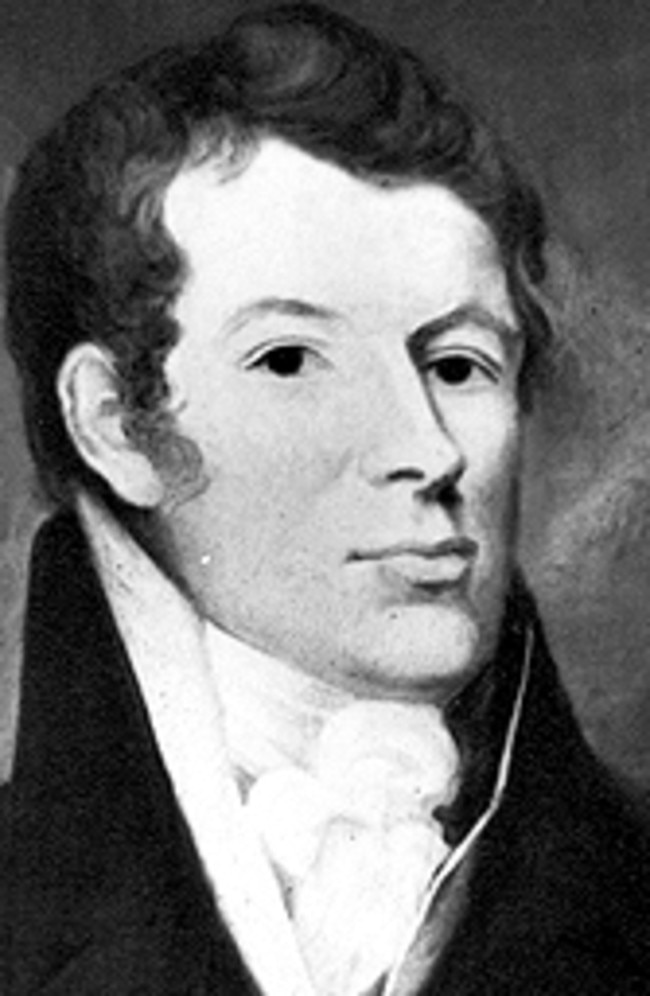

HIS portrait shows a determined man, chin tilted upwards and mouth set in a proud curve.

This is John Macarthur, one of Australia’s founders, responsible for establishing our wool industry and the face of the now-defunct $2 note.

Yet he ended his days shorn of his dignity, having been declared a lunatic.

Macarthur was known for his confrontational manner and risky behaviour. He was arrested several times, was one of the instigators of the rum rebellion and was known to be fiercely argumentative in business. But the Plymouth-born entrepreneur was not just a troublemaker, he was a shrewd and resourceful negotiator.

He arrived in Australia as an officer of the New South Wales Corps in 1790. The acting-governor of NSW wrote of him: “There are no resources which art, cunning, impudence and a pair of basilisk eyes can afford, that he does not put in practice.”

Macarthur was one of the first colonisers to acquire merino sheep imported from England. He struck deals, used convict labour and laid the foundations for the country’s wool industry. After entering Sydney with a debt of 500 pounds ($1000), he turned it into a 10,000 pounds ($19,000) within ten years, a vast sum at the time.

He joined the Legislative Council in 1829, but just three years later, he was taken to Liverpool Lunatic Asylum by his family and pronounced insane.

“He is now a wayward child and remains at home brooding,” wrote Governor Ralph Darling.

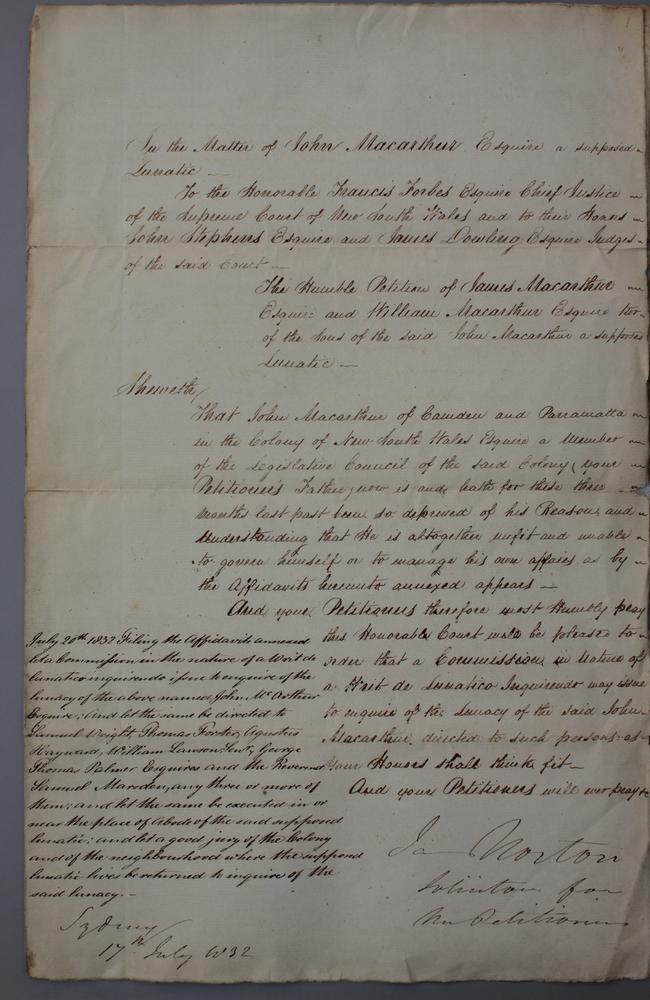

The declaration of his lunacy reads: “John Macarthur … for these three months last past, (has) been so depressed of his reason and understanding that he is altogether unfit and unable to govern himself or to manage his own affairs.”

Officials observed there was “little hope of restoration”.

He died in April 1834, aged 65, and was buried at Camden Park.

Macarthur’s wealth means his wife Elizabeth and children were probably able to care for him at home. Those who were not part of the privileged elite faced a far worse fate.

The asylums of the 1800s were bleak prisons, where inmates were shut away in cells with no toilet facilities. Unable to care for themselves, most existed in appallingly dirty conditions, experiencing little contact with the outside world or even those locked away next door.

“Very often in those days they were just held, taken out of polite society,” says Ben Mercer, senior content director at Ancestry.com.au. “Sometimes these records can be quite confronting. One little boy in Newcastle was unable to eat and starved to death.”

There was little understanding of mental illness at the time, Mr Mercer told news.com.au, so if people were considered “incoherent”, they were often disowned by society and their family.

Mentally ill people were frequently found living on the street, as we sometimes see today. Children whose parents had died — who were frightened, homeless and suffering from behavioural problems — would also be locked away.

“There were lots of women going through childbirth too, often after childbirth they would have the ‘baby blues’, which we now know to be post-natal depression,” said Mr Mercer. “There were cases where mothers who didn’t know how to cope killed their children.”

In some instances, asylums were seen as “safe harbours” for those who would otherwise end up destitute or dead. But people who died in asylums usually do not have death certificates, and are therefore hard to trace. Families researching their history would do well to check asylum records.

Macarthur was remembered as a hero after his death, and the ignominious circumstances of his final years faded into obscurity.

Liverpool Lunatic Asylum closed down in 1838 and benevolent societies began caring for mentally patients. In 1966, Australia honoured Macarthur’s contribution to agriculture on the $2 note, which depicted his profile and symbols for wool and wheat.

“Every family probably has someone in its records who may have had mental health problems,” says Mr Mercer. “This shows it can happen in any family, even one of the key families in Australian history.”