This chart will change the way you think about supermarket shopping

One simple chart has completely blown up the way we understand supermarket shopping as consumers everywhere feel the crunch of inflation.

You have to see this next chart. It blows up the way we understand supermarket shopping.

It was published by the Bureau of Statistics for an academic conference, based on information from supermarkets.

It’s astonishing the supermarkets let this data out into the public, because it reveals their secrets.

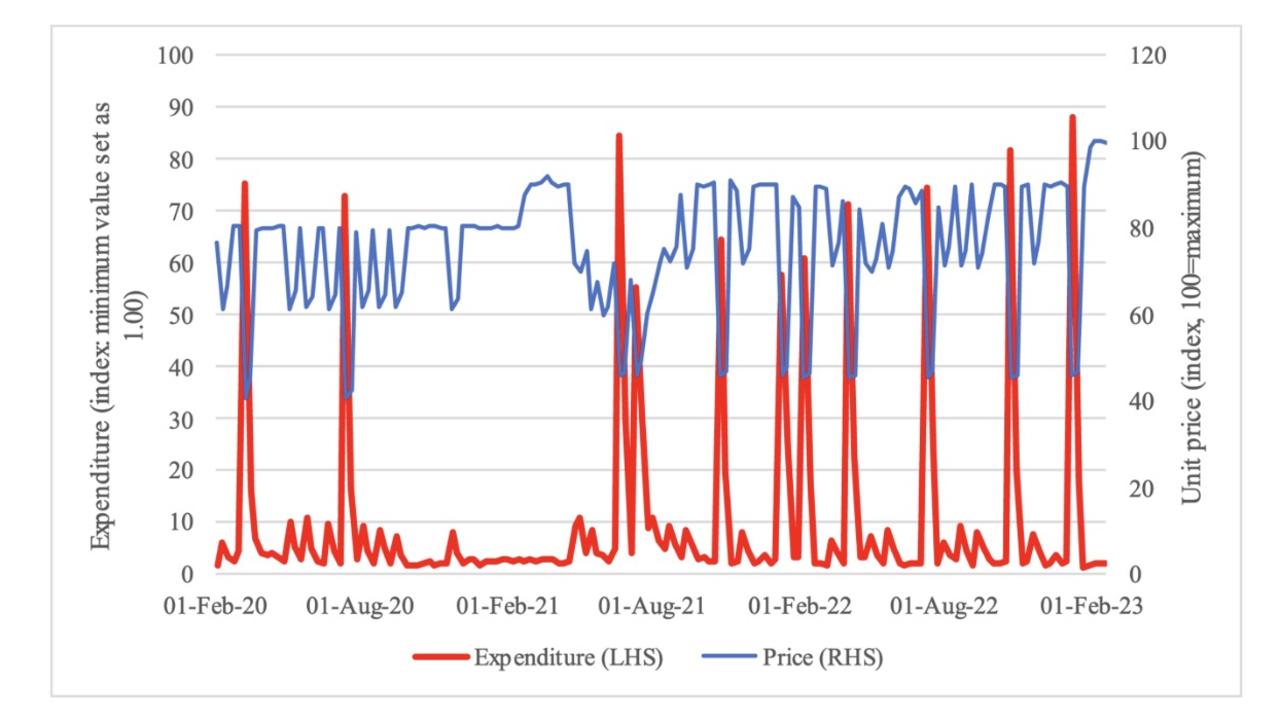

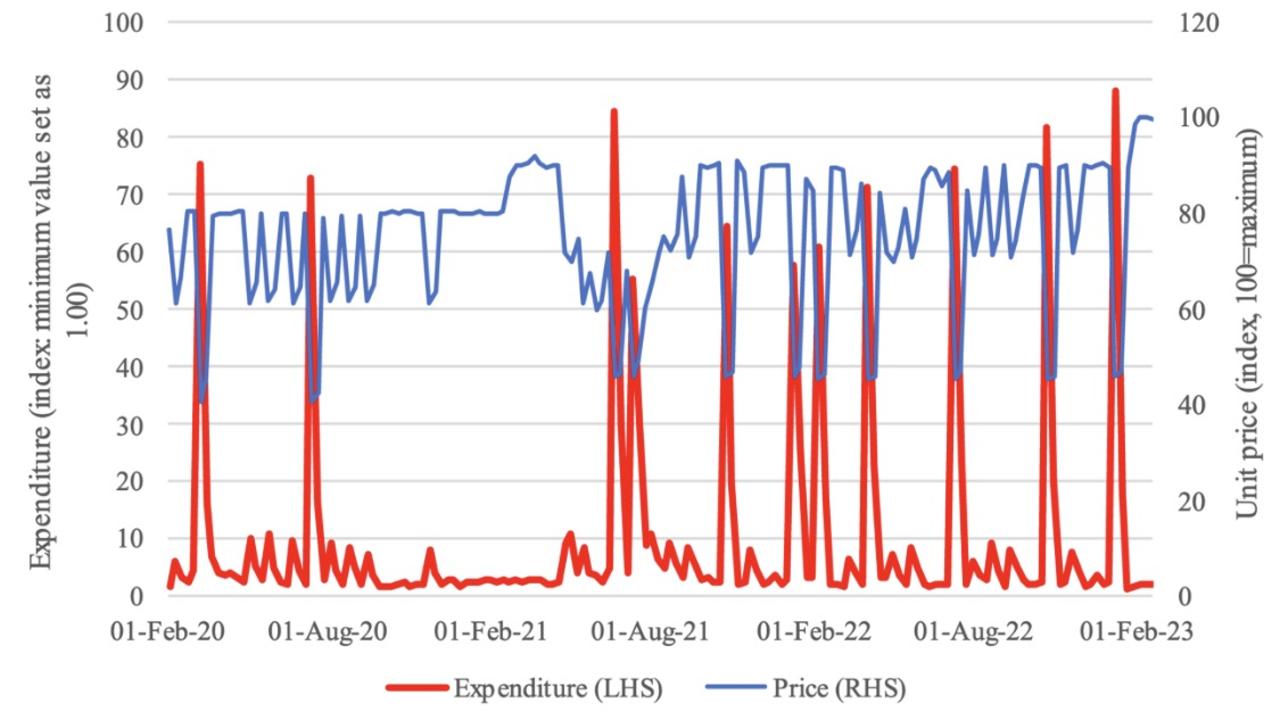

This chart shows the price of a certain kind of olive oil, and amount they sell. The blue line is the price. Note it’s not in dollars and cents, the numbers are set so the highest price it sells for is 100, and when the olive oil has a 25 per cent off sales the line shows 50, etc.

You can see the line goes up over time since 2020, as we’d expect, and you can also see the supermarket regularly puts this olive oil on special, including 11 times when it was 50 per cent off.

When it does, sales of olive oil go absolutely berserk. That’s the red line. The red line goes up when the blue line goes down. Not just a little bit.

Usually the supermarket sells maybe $50 worth of olive oil in a given time period. When the oil is on a 50 per cent off sale, they sell up to $750 worth. Call it a 15-fold increase in expenditure. And since the oil is half price, it’s actually a 40-fold increase in the number of bottles sold.

That is an absolutely incredible increase and it explains why supermarkets put things on special: specials are incredibly powerful.

They clog the checkouts. People get excited. They stuff their trolley and take things home to fill the back of their cupboards. Specials make the checkouts ring.

But it raises a serious question.

If they sell 20 or 30 times as much product when the product is on special as when it’s not, what’s the real price? Sure, most of the time it is priced at $10. But at those times the product just sits there, not getting bought. Most people who buy it pay $5.

Is $5 the real price of the product? Is the higher price just for a handful of suckers?

Why supermarkets have a complicated relationship with discounts

From a shopper’s perspective, specials are awesome. But supermarkets feel conflicted. The problem is if they sell some of that olive oil to people who would have bought it anyway. The sale price is wasted on those people – they didn’t need to discount it to get the product into their trolleys. And when a regular shopper buys an item on special, the supermarket can lose a lot of profit.

Imagine an item that costs the supermarket $4.50 to buy, which on sale at $10. They

make $5.50 profit. If they discount it to $5, they only make 50c profit. Sales would need to be 11 times higher to compensate. (11 times 50 cents = $5.50)

What’s more, if the product can be stored up, the regular shopper might buy a lot of items when it’s on sale and stash them in the pantry, so they never need to buy at the regular price again. Discounts can actually destabilise sales for the supermarket and undermine their ability to set prices in future.

So, yes, supermarkets love discounts, because they want to make a lot of sales, but they hate discounts, because they also want to make a lot of profits.

Supermarkets in Australia tried for years to break their addiction to discounts. They wanted to be more like Walmart, the American grocery store considered to be the world’s most dominant bricks and mortar retailer. It is famous for not doing discounts. Instead they offer what they call “every day low prices”.

That strategy became a huge retail trend worldwide in the last two decades or so. Aldi does this. Sure it has special buys, but those are weird items. It does very few specials on its normal grocery range.

Bunnings and Chemist Warehouse have every day low prices too. They don’t chuck things on special, instead they have a price-leader image.

For many years Coles and Woolies also tried to do more “every day low prices”. They wanted to be more like Walmart, although they struggled with their addiction to putting things on special.

You still see signs of it with the Coles “dropped and locked” pricing strategy. But every day low prices seem to have gone out of fashion more recently. I guess it has been hard to keep prices consistently and predictably low through the pandemic when input prices keep rising.

These days the big two chains in Australia are proudly offering lots of specials again. I contacted Woolworths for this story and a spokesperson boasted that they have 6000 different items on special every week. Certainly specials can create the impression of low prices and great value with big splashy sales, even if prices are, by some accounts, soaring up even faster than our heady rates of inflation.

Targeted, tailored, personalised

There’s nothing better than coming across a discount on something you were going to buy anyway. And there’s nothing a supermarket likes less.

This is why they love to talk about being “smart” about promotions. In their dreams, they’d love to offer a discounted price to people who wasn’t going to buy it, and a normal price to people who would have bought it anyway.

This is why all the membership programs, like FlyBuys and Everyday Rewards are so valuable to the supermarkets. They can track our purchases. They learn a lot about who only buys stuff when it’s on special, and who buys stuff no matter the price. This may let them try to offer specials to people who might actually respond, not people who were going to buy that stuff anyway.

The word “personalised” keeps popping up in their corporate documents.

For example, Woolworths CEO Brad Banducci spoke about “personalised Everyday Rewards member offers” while he was announcing the most recent sales results to the market. Which I reckon means you’re getting offered specials I’m not, and vice-versa.

More Coverage

They can offer discounted products in one store but not another, for example. Apps and online shopping offer an even bigger opportunity to let some customers have discounts when others don’t.

The supermarkets would love to smooth out that red line in the chart above, by making sure everyone who is going to buy something anyway isn’t just buying it on special.

Jason Murphy is an economist | @jasemurphy. He is the author of the book Incentivology