We really don’t trust our government or institutions anymore

WE REALLY don’t trust our government, media or institutions anymore. And as the gap between elites and everyone else grows, it’s only going to get worse.

THE world is in a crisis of trust. People don’t believe the institutions that are supposed to work for them are actually doing so.

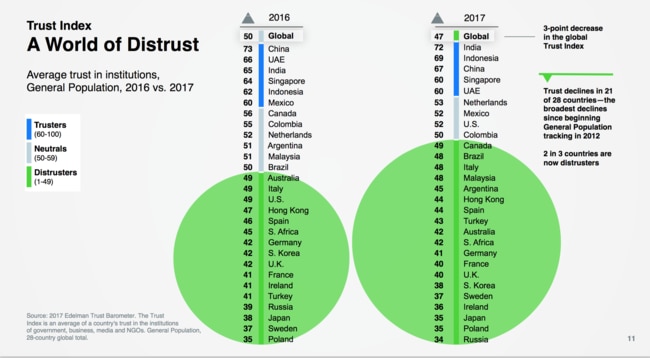

A brand new survey of tens of thousands of people around the world shows trust has fallen dramatically in dozens of countries. And Australia is one of the worst.

In Australia, the share who trust in government, non-government organisations, media and business has fallen to 42 per cent, down from 49 last year. The numbers come from a survey which is run each year by Edelman, a consulting firm.

Australia is now even behind America, where trust is now rising, from a low base. I look at all this and can’t help thinking one thing. It’s a quote from Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign.

“It’s the economy, stupid.”

That sparkling diamond of political insight was an informal campaign slogan for Clinton back in ’92, when he took on George Bush Senior and won.

MONEY TALKS

The economy matters. Bad economic conditions cause big backlashes in politics, and we could not have seen a clearer depiction of that than when Donald Trump mounted the dais and was made President of the United States of America.

While Bill Clinton benefited from the 1991 recession, research from Europe has shown that when you have a financial crisis and a recession, (like our most recent global financial crisis) the vote of the far right wing goes up.

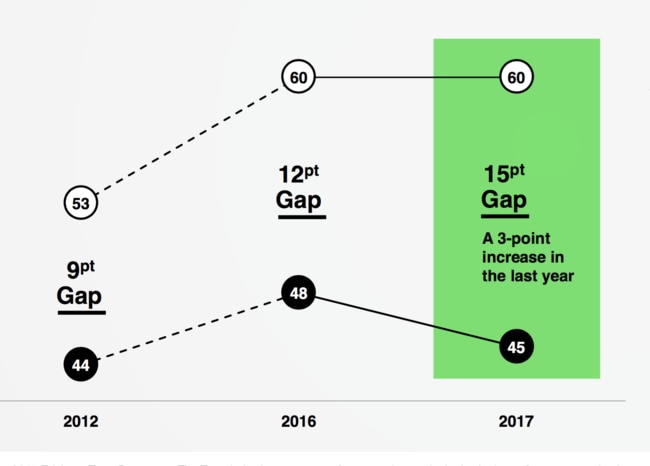

A link between the economy, trust, and political anger would be logical in theory. And I’m pretty sure it exists in practice. What makes it crystal clear is the split between elites and masses, as shown in this next graph

Elites have prospered since the GFC. It makes sense that trust among elites is strong, while trust among everyone else is low.

The trust gap is rising.

The top line shows trust among a group of people who are in the top 25 per cent of household incomes for their age group, aged 25-64, college-educated, and who consume a lot of business and general news. Anyone who doesn’t meet all four criteria is in the bottom line.

You can easily see that the average person is far less trusting in government, non-government organisations, media and business. A lot of commentators argue the problem here is that these people are uninformed and disengaged. But what if, just maybe, those organisations are not doing the right thing by them? What if those organisations have not earned their trust?

GETTING BY, BARELY

In many rich countries, since the GFC, we’ve seen rising inequality. Oxfam put out a report just last week, showing that eight people own as much net assets as the poorest 50 per cent of the world’s population!

Seems to me that in some countries there is a problem with how the economy is run. That often tends to hurt the least well-off. An example of this in Australia is rising underemployment.

Underemployment is much higher than unemployment, and has been rising even at times when unemployment was falling. Combine that with stagnant wages for most people and you have a perfect explanation for a very rebellious streak in the electorate.

Even in Australia we’ve seen a swing to the right as trust has wavered. Pauline Hanson is the purest example, but there are others. We may have moderate Malcolm in the Lodge, but he is very much limited by far more conservative politicians like Tony Abbott and Senator Cory Bernardi. The constant chatter about a breakaway conservative political party is another sign that the further reaches of the political right are up and about.

The big question here is whether more right-wing governments that sometimes get elected when people have a shortage in trust are actually good at fixing the economy. If not, the lack of trust is likely to keep on going.

Jason Murphy is an economist. He publishes the blog Thomas The Thinkengine. Follow Jason on Twitter @Jasemurphy