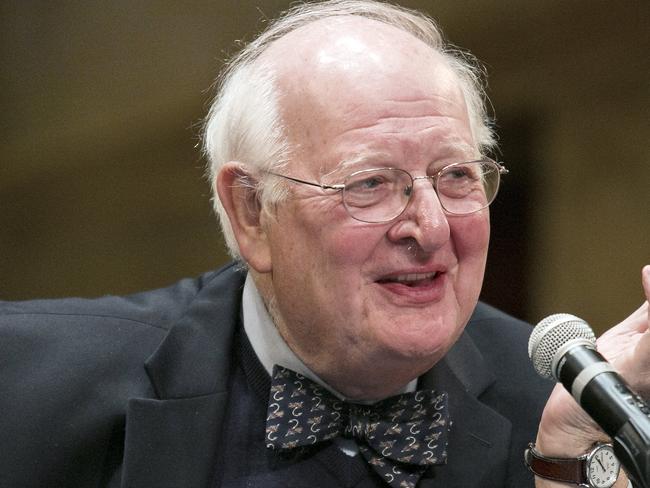

Princeton University economist Angus Deaton wins Nobel Prize for his work on poverty

“I’m just hoping it’s not a dream which I’m going to wake up from,” says the winner of the 2015 Nobel Prize for Economics, still pinching himself.

THE winner of the Nobel Prize for Economics has joked that he thought the telephone call from Sweden alerting him that he had won might have been a prank.

Princeton University economist Angus Deaton, who was honoured for groundbreaking work on poverty and data collection, knew he had been on the shortlist but said he did not expect to win.

“I was not lying in bed at six o’clock this morning thinking ‘oh that phone call should come,’” the academic, 69, told a news conference yesterday.

“There was a very Swedish voice, which is almost enough, who said I would like to speak to Professor Angus Deaton, there is a very important telephone call for him from Stockholm. And then I had a pretty good idea what it was and then they said some very nice things about me, which was very nice,” he said.

“Then they were very keen to make sure I did not think it was a prank ... and of course as soon as they said that I thought ‘oh my gosh, maybe this is a prank,’” he said.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences praised his groundbreaking work using household surveys to show how consumers, particularly the poor, decide what to buy and how policymakers can help them.

Deaton’s research has raised doubts about sweeping solutions to poverty and about the effectiveness of aid programs. He has dug into obscure data to explore problems ranging from poverty in India to how poor countries treat young girls, and the link between income inequality and economic growth.

Last year, he spoke out about his concern that high-paying jobs in finance and other fields were diverting talented young people from “more worthwhile pursuits.”

He also warned that the very rich might be using their disproportionate influence to “write the rules in their favor, and they may work against the public provision of health care or education, for which they pay a large share but have little personal need.”

For work that the award committee said has had “immense importance for human welfare, not least in poor countries,” Deaton, 69, will receive a prize of 8 million Swedish kronor (about $975,000) from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Deaton’s research has “shown other researchers and international organizations like the World Bank how to go about understanding poverty at the very basic level,” said Torsten Persson, secretary of the award committee.

“That lightning would strike me seemed like a very small probability event,” Deaton said. “There are many people who are worthy of this award.”

Deaton grew up in a family of modest means. “Not having money can give you a perspective on the world that you don’t get other ways,” he said.

“Most people in my family thought I should be out (working) in the fields, not reading books. Fortunately, my father didn’t think that way.”

“Thinking about numbers hard is one of the things I think is really important,” Deaton told The Associated Press.

He created tools that let governments in poor countries study how families adjust spending in response to, say, an increase in the sales tax on food.

“He’s an economist’s economist,” said Dani Rodrik, a Harvard colleague.

Deaton has done “very careful, detailed work” on data about poverty at the household level in poor countries “so that one could understand the effects of changes in policies on how people behave,” Rodrik said.

Deaton discovered that India had far more poor people in rural areas than previously thought, a finding that led the government to expand subsidies.

“Households that were not defined as poor before can now be reached,” said Ingvild Almas, associate professor at the Norwegian School of Economics. “That is a direct result of Deaton’s research.”

Deaton also hit upon what the Nobel committee called an ingenious way to discover whether families in poor countries spent less to care for daughters than for sons.

Among other things, he studied how much households spent on “adult” items, such as beer and cigarettes, to see whether families consumed things differently depending on the sex of newborn children.

His surprising conclusion: They didn’t.

Another Deaton study challenged the once-popular notion that malnutrition caused poverty by making people too weak to find work. He found the relationship worked the other way: Being poor caused people to be malnourished.

Deaton is physically imposing. “He has football player dimensions,” said David Warsh, who writes the Economic Principals blog. And he isn’t reluctant to voice unpopular opinions.

In his 2013 book, The Great Escape, Deaton expressed skepticism about the effectiveness of international aid programs in addressing poverty.

He noted, for example, that China and India have lifted tens of millions of people out of poverty despite receiving relatively little aid money. Yet at the same time, poverty has remained entrenched in many African countries that have received substantial sums.

Deaton’s book drew criticism from Bill Gates, who runs a foundation dedicated to fighting global poverty. The billionaire founder of Microsoft found Deaton’s critique of aid programs too broad.

“If this is the only thing you read about aid, you will come away very confused about what aid does for people,” Gates wrote on his blog last year.

Deaton has criticized the widening income gap between rich and poor in the U.S. But he has not become a darling of anti-inequality activists the way another Nobel-winning economist, Columbia University’s Joseph Stiglitz, has. That may be because his views on inequality are complicated.

In The Great Escape, he wrote that “inequality can sometimes be helpful” in promoting prosperity by giving people incentives to work harder and more efficiently.

Monday’s announcement concluded the selection of this year’s Nobel winners. The economics award isn’t among the original prizes created by Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel in 1895; it was established generations later as a memorial to him.

Deaton, who spends part of his summers fly fishing in Montana, told the AP that he has no big plans to celebrate.

“I’m just hoping it’s not a dream which I’m going to wake up from,” he said.

AP writers Nathalie Rotschild in Stockholm; Nirmala George in New Delhi; Bruce Shipkowski in Princeton, New Jersey; and Geoff Mulvihill in Haddonfield, New Jersey, contributed to this report.