‘Every time you buy less’: Venezuela teeters on the brink

IT HAS loads of oil and should be one of the richest countries on the planet, but most of its people only make $7 a month.

WITH more oil reserves than anywhere else in the world, Venezuela should be drowning in riches.

Instead, the country, and its 30 million inhabitants are on the brink of collapse: financially, and, for many, physically.

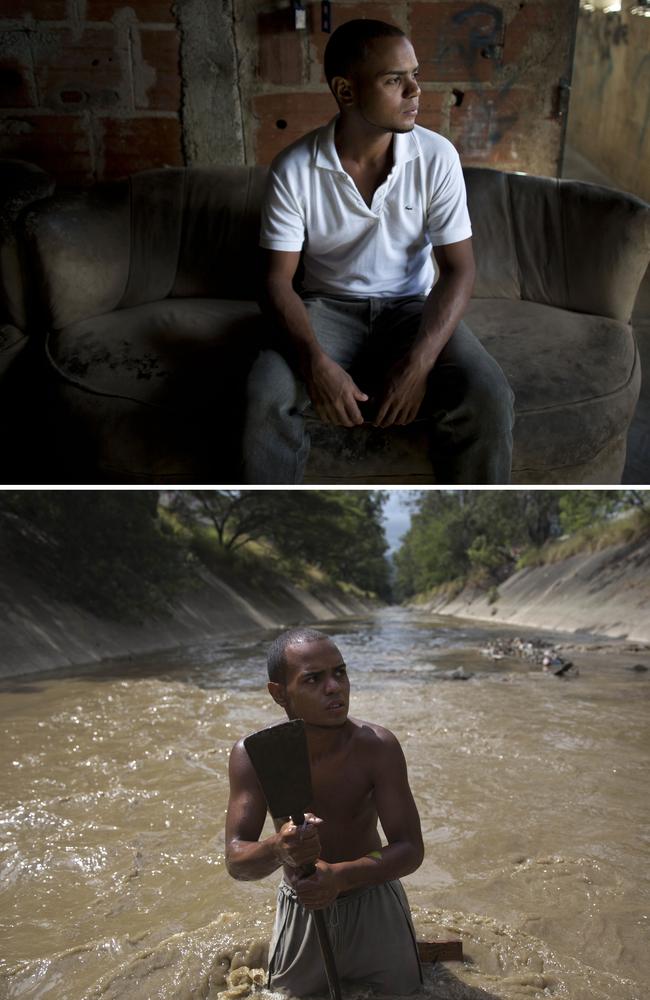

In Caracas, the capital, men scavenge daily in the putrid Guaire River.

They pour down from the barrios, raking their hands through stinking, toxic mud in the hopes of finding the tiniest bit or metal, jewellery — anything of value — that they could sell for food.

Nearly two decades of socialist rule during which food and oil production have plummeted amid poor management of state resources and a drop in world crude prices have driven many Venezuelans into desperation and bloody civil unrest.

The minimum wage for public employees in Venezuela is less than $7 a month at the black market exchange rate. Food is increasingly hard to find or afford.

A common scene in Caracas is poor Venezuelans scouring garbage piles for food.

An estimated 75 per cent of Venezuelans lost an average of 8.7 kilograms last year, according to one recent survey, AP reports.

Make it to the market, and the funds don’t go far.

“Every time you go shopping you buy less and your budget is limited to food,” 50-year-old tourism employee David Ascanio told AFP as he shopped in a Caracas market.

In the lead-up to Christmas, there were riots by protesters desperate for food and financial relief. There were reports of looting across the country.

It wrapped a year of violent protest, desperation, frustration, and demand for political and economic reform and an end to authoritarian rule in a country at the point of collapse.

WHAT HAPPENED?

Venezuela — once one of Latin America’s wealthiest countries — is a country in crisis, and a place of contradictions.

It boasts the world’s largest oil reserves, and the world’s highest inflation — which hit a staggering 2600 per cent last year, according to figures released on Monday.

About 95 per cent of dollars in Venezuela are from sales of oil. Selling and pumping less and less has left the country in financial crisis.

But that revenue stream has been fading as the country’s economic crisis and unpaid debts have steadily eroded production.

Oil prices are half their peak from 2008 — and still plummeting.

The country’s oil output has fallen 12 per cent over the past two months, according to the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. The 1.7 million barrels it’s producing a day is the lowest since 2002.

The oil infrastructure has crumbled as the government of socialist President Nicolas Maduro followed in the footsteps of his predecessor, Hugo Chavez, whom Maduro succeeded in 2013.

But Venezuela has defaulted on some of its debt. And the cash-strapped country owes plenty more.

In 2003, then-president Chavez fired about half the workforce of the state-run oil corporation, Petroleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), for taking part in a strike. PDVSA never recovered, Venezuelan oil expert Faranciso Moanlsi told Public Radio International.

After Chavez came to power the price of oil hit around $100 a barrel and he poured money into infrastructure including roads and education.

There are reports he even went around buying fridges and food for people at election time to try and get people to vote for him.

But the money was taken away from an industry which takes massive amounts of money — at least $8 billion a year in Venezuela, Monaldi estimates — to maintain.

DEBT DEFAULTS

The government was investing half. And when oil prices collapsed in 2014, the debts mounted.

Maduro’s leftist government has cut food and medicine imports by more than 70 per cent since 2013 to preserve limited resources for debt payments.

But it’s not meeting them either.

In November it defaulted on its sovereign bonds, failing to pay interest on two US dollar-denominated bonds by the end of a grace period on November 13.

The default figure was $1.2 billion, according to Caracas Capital, a firm in Miami that tracks the country’s debt, reports CNN

While that’s a relatively small sum in the world of bonds. it may be a sign of what’s to come, with bondholders owed more than $60 billion — if the creditors call it all in.

GRIM REALITY

In a bid to hold onto his power, President Maduro last week decreed a 40 per cent increase in the minimum wage to try to contain the crisis, in the wake of the food protests.

He even tried introducing a ‘petro’ cryptocurrency to raise funds — a move outlawed this week by Venezuela’s opposition-run parliament.

Caracas locals like Luis Briceno — who built up a small bottle branding business over the past 25 years, but stands to lose it as the economic crisis worsens — say it won’t help.

In fact, it will make things harder.

“This New Year is criminal,” he told AFP, reflecting the anguish of millions of Venezuelans facing acute shortages sparked by falling oil prices, political unrest and corruption.

“It seems criminal, because ask the workers themselves if they want the government to increase the minimum wage and they say no, because the next day everything increases.” Although he tries to avoid thinking about it, the 70-year-old businessman knows that the next few months will be crucial for his small firm, which is already battling a shortage of supplies and the hyperinflationary spiral.

13 MILLION PEOPLE, $7 A MONTH

Despite Maduro’s announcement of a minimum-wage increase, most Venezuelans will still earn only about $7 a month in salary and food vouchers, based on the commonly-used black market exchange rate.

The government says 13 million Venezuelan workers earn the minimum wage or receive the vouchers, out of a workforce of 19.5 million.

Ever-rising inflation means the basic income barely buys a basket of staples like kilo of meat, 30 eggs, a kilogram of sugar and a kilogram of onions.

Last weekend, the government forced more than 200 supermarkets in Caracas to lower prices, causing huge lines to form outside as Venezuelans jumped at the chance to stretch their scant funds.

In the business district of the capital, 53-year-old housewife Raquel Benarroch told AFP she had little hope.

“Before, we saw the bottom of the abyss,” she said.

“Now we see things much blacker than that.”