Donald Trump’s ‘new world order’ leaves Australia ‘in doubt’

Donald Trump is already creating a “new world order” weeks into his presidency – and Australia is at risk of being “caught in the crossfire”.

Does might make right?

It’s a question threatening to upend Australia’s place in the world.

For a nation built on trade under a post-World War II international legal framework, the ideal of a level playing field is rapidly diminishing.

For a nation that prides itself on quickly responding to the needs of its allies and partners, the idea of mutual support is suddenly in doubt.

It’s US President Donald Trump’s new world order.

He’s threatening friend and foe alike with trade – and military – intervention. World Trade Organisation rules and arbitrations are being replaced by coercive bilateral contracts.

MORE:‘Hate’: Ivanka lifts lid on leaving Donald Trump

“These deals will not be free trade agreements,” argues independent trade analyst Stephen Moran.

“We should be under no illusion that any ‘dirty deals’ would be World Trade Organisation-compliant or that our free trade agreements would prevent them.”

And longstanding military pacts increasingly have financial, not moral, overtones.

“Trump’s behaviour should make us think again about the limits of the alliance,” says Lowy Institute international security director Sam Roggeveen.

“It is a far shallower and more transactional thing than its Australian supporters like to believe.”

It’s a world where China is already up-ending the established rules-based order.

It’s already wealthier than the US. Its navy is rapidly overtaking the US’s lead. Its diplomatic reach is expanding relentlessly.

“What will happen if the United States jettisons its values, trashes its institutions, and continues to throw its weight around?” asks Professor Howard French of Columbia University.

“What would the argument be for siding with Washington versus Beijing anymore or forging other alliances and arrangements?

“If the United States continues down its present path, we may soon find out.”

Australia’s been here before

In April 2020, then-Defence Minister Marise Payne made a public call for the World Health Organisation to investigate the origins of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Beijing was outraged.

It immediately slapped punitive tariffs on Australian barley, copper, sugar, beef, coal, timber and wine.

Then, its Sydney embassy issued a 14-point grievance list demanding everything from the closure of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) to the overturning of anti-foreign interference laws.

Beijing’s belligerence was not entirely unexpected.

“China is a big country. And you are small countries. And that is a fact,” China’s top diplomat told ASEAN nations complaining about its aggression in the South China Sea in 2010.

Prof French says this marked the start of “the so-called wolf warrior era when China would make no apologies for its actions while demanding that other nations yield to its desires. He demonstrated that his country was a revisionist power — one willing to lay waste to the existing world order and the rules that underpin it in the narrow pursuit of its national interests”.

Beijing’s attempts at coercion failed.

“Our economy proved itself to be remarkably resilient and these sanctions have all been lifted, with the last to go being on lobsters in late 2024,” says ANU Professor Jenny Gordon.

“Australia did not retaliate … One of the few bipartisan positions from the major political parties in Australia is that raising tariffs in retaliation is a bad idea.”

But the question of how to cope with economic coercion may soon be on the cards once again. This time, from “friendly fire”.

“A little more than two weeks since President Donald Trump returned to the White House, the United States — a country that usually emphasises its support for the longstanding conventions of an orderly international system, whatever the contradictions — has become the most revisionist state the globe has seen since World War II,” Prof French concludes.

Caught in the crossfire

“Australia and Canada are so alike. Canada is safe, likeable, reasonable, wealthy, friendly, Western, English-speaking … and a long-established alliance with the United States, reinforced by deep historical, economic and cultural ties,” Prof Roggeveen states.

“All of which ought to make us wonder: if the Americans can impose a 25 per cent tariff on Canadian goods entering the US … what should Australia expect?”

Mr Trump offered a multitude of justifications for his threats of tariffs on Canada and Mexico. It was about immigration. It was about the illegal drug fentanyl. It was about trade deficits.

He’s threatened the European Union with tariffs but has not yet explained why. Presidential “First Buddy” Elon Musk’s dislike of the EU’s attempts at regulating social media and AI may have something to do with it.

“What might the United States demand of Australia, and what tariffs might be used as a coercive tool?” asks Prof Gordon.

Australia has a significant trade deficit with the US. But that may not be the protection many hope it to be.

US big tech players have bought open access to the White House. And they’re angry at Canberra’s moves to ban under-16s from accessing unregulated social media.

“To what extent will the Australian government allow social or other policy to be dictated by US business interests?” asks Prof Gordon.

“Is ceding sovereignty to avoid a small loss from a tariff a cost Australians would be willing to pay?”

Other Australian products also compete with US interests.

Canberra restricts beef, pork, turkey, apple and pear imports – mainly due to biosecurity concerns. Then, there are minimum requirements for Australian content on media services.

Critics argue these are excuses to disguise tariffs.

But the greatest threat, analysts agree, will be the fallout from other global moves.

“A hidden risk for Australia’s exports is that of discrimination resulting from US trade deals with other countries,” warns Moran.

“Regardless, the multiple justifications offered for the tariffs – from addressing trade deficits to raising revenue to forcing diplomatic concessions – reveal their true nature as negotiating tactics rather than coherent policy solutions,” argues Monash Business School associate dean Nicola Charwat.

Dances with wolves

“None of this should be read as a call for Australia to end the alliance with the United States,” insists the Lowy Institute’s Roggeveen.

“No matter how badly Trump behaves, the pact has benefits to Australia, which gets privileged access to intelligence and weapons technology, and opportunities to train and exercise alongside American forces. That’s worth preserving.”

But damage may be inevitable.

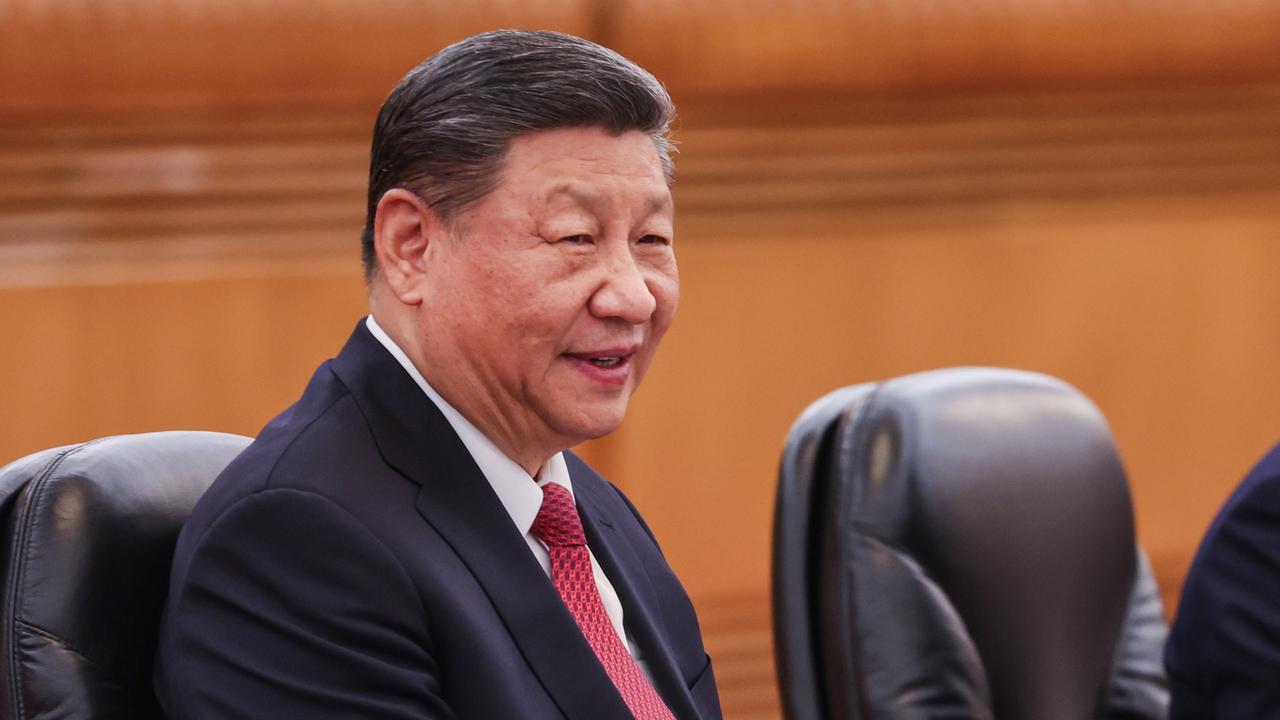

Chairman Xi Jinping’s belligerence backfired. Instead of forcing capitulation, his attempts at economic coercion provoked international pushback.

“Wolf Warrior” politics is no longer fashionable in Beijing.

“Perhaps the best evidence of the failure of China’s sharp turn, though, lies in its own course correction,” Prof French writes.

“It is safe to assume that Beijing’s national interests haven’t changed much, but its diplomatic strategy certainly has. In recent years, China’s most vociferous diplomats have become much more likely to voice support for the international system, free trade and open markets, and co-operation with other states.”

Is it a lesson President Trump will also be forced to learn?

“Trump’s tariffs are not just (or even) about economics. They are about coercion,” argues Prof Gordon.

“The purpose of China’s sanctions was never clear, more a warning shot to other countries to not offend China’s sensibilities. Trump is likely to be much more explicit in what he wants.”

And Washington DC has more to lose on the international stage.

“Maintaining credibility means the United States must honour its commitments, whether in trade agreements, security pacts, or international accords,” argues Luck.

“If the United States exercises its economic statecraft toolkit capriciously and proves itself to be an unreliable and unpredictable partner, it will not only lose the support of its allies, but it will also diminish the effectiveness of those very tools it recklessly wields.”

Meanwhile, the rest of the world may have to find its own way to establish and maintain credible, rules-based trade agreements.

“As the global economy grapples with this new reality, the key question becomes not whether nations will resist US pressure, but how they will reconstruct trading relationships in a world where economic nationalism has replaced multilateral co-operation as the driving force of international commerce,” warns Charwat.

“Trump’s tariffs may be just the opening salvo in a broader transformation of global trade.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @jamieseidel.bsky.social