China flooding foreign markets with cheap goods is ‘a situation structurally primed for war’

China is flooding the world with cheap goods again and one expert warns it’s a “situation primed for war”.

Turmoil in global minerals markets as China floods the world with cheap goods highlights a situation “structurally primed for war”, defence analysts have warned.

Collapsing iron ore prices threaten to wipe out tens of billions of dollars from the profits of Australia’s largest miners, while “carnage” in battery minerals nickel and lithium over the past year has led to now-unprofitable projects being delayed or cancelled.

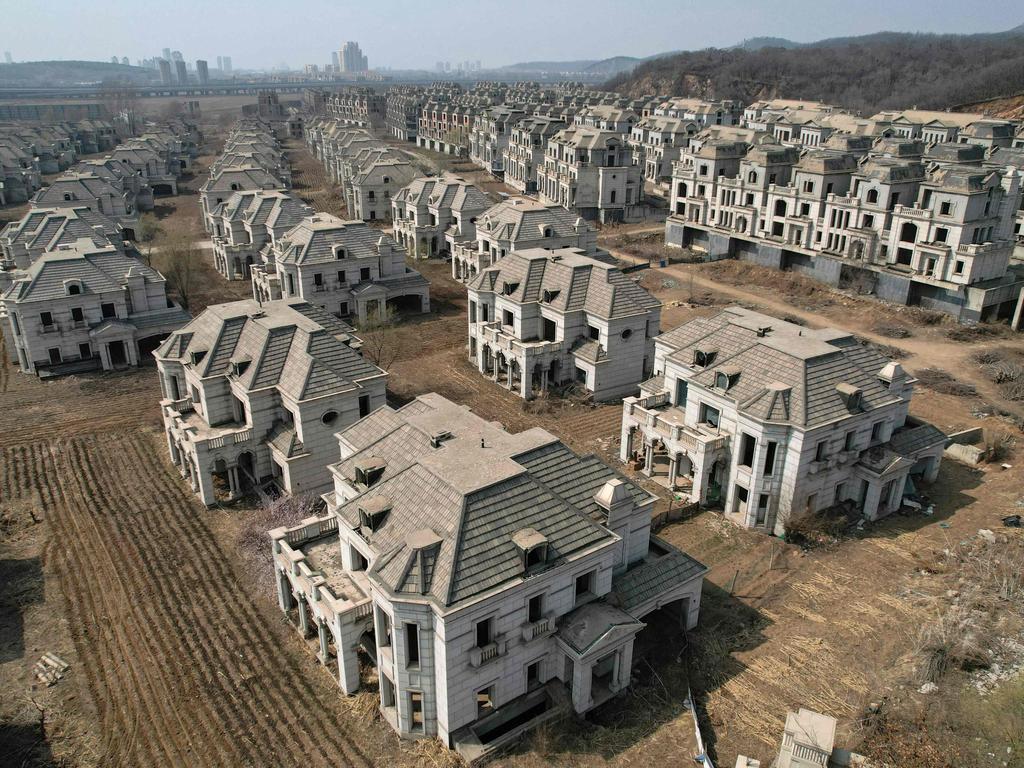

The current chaos in iron ore is largely due to the implosion of China’s over-inflated real estate bubble, which for years has consumed vast quantities of the key steelmaking ingredient, mostly from Australia, sending shockwaves through the every level of society and sparking frantic efforts by Beijing to revive its economy.

Now those efforts include doubling down on exports such as cars, machinery and consumer electronics, propped up by cheap, state-directed loans, according to The Wall Street Journal, which warns the globe may be facing a repeat of the “China shock” of the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Whereas the first China shock saw a boom in cheap Chinese-made goods like furniture, toys and clothes that helped keep inflation down – but wiped out manufacturing jobs in the West – this time China is competing in higher-value industries that are “more fundamental” to technological leadership, Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor of economics David Autor told the newspaper.

“Beijing is seeking to engineer an economic turnaround by ploughing money into factories, especially for semiconductors, aerospace, cars and renewable-energy equipment, and selling the resulting surplus abroad,” the Journal reported this week.

“Unlike in the early 2000s, however, the Western world now sees China as its chief economic rival and geopolitical adversary.”

Amid the faltering housing market, China’s steel mills similarly diverted surplus output onto export markets, adding to what the OECD has called a “crisis” of excess steel supply.

“China’s mills shipped 90 million tonnes of steel to export markets last year, a 36 per cent increase from the previous year and the highest since 2016,” David Uren from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) wrote last month.

“While the Australian budget is reaping a bonanza, Western steel mills, including Australia’s Bluescope Steel at Port Kembla and the Whyalla Steelworks, are coming under pressure. Steel has for decades been one of the most politically sensitive international markets and the surge in China’s steel exports will contribute to an increasingly acrimonious international trade environment over the year ahead.”

Elbridge Colby, a former Pentagon official who led the Trump administration’s policy pivot identifying China’s rise as the key challenge for the Department of Defense, said it was “a situation structurally primed for war”.

“Why? China has vast overcapacity it must export,” Mr Colby, founder of The Marathon Initiative think tank, wrote on X. “Now countries don’t want to import so much from it. Where will it export to? It needs markets. Markets can be gained by force.”

Michael Shoebridge, founder and director of Strategic Analysis Australia, said it was clear “China is capturing new global markets and it is owning the supply chains for those markets”.

“Dual circulation is Xi Jinping’s signature economic strategy and it is to do two things — make China less dependent on other economies, and make other economies more dependent on China,” he said. “That is the lens to view this through.”

Mr Shoebridge said electric vehicles were the most obvious example.

“With the current policy settings across the world from Europe to Australia, BYD’s dominance looks assured because they will use their huge excess capacity and protected market position to crush all other rivals by pricing them out,” he said.

“Deflation in China and low growth makes their prices more compelling and means they must export to stay in business. So that trend’s all bad, then you look at the minerals side of things — the Chinese are working very hard on alternative supply chains for critical minerals that aren’t from Australia and also alternative suppliers for our bulk export, iron ore. That’s what the big Guinea mine [Simandou] is all about, sure it’s taking a long time but they’re determined.”

Mr Shoebridge said Australia “has this real problem that we’re stuck pretending that the pre-pandemic, globalised economy still exists and that it’s just about us producing stuff at a compelling price and getting it bought” — but the rest of the world had begun returning to “nationalistic” policies in the face of China’s “deeply mercantilist” behaviour.

“The pandemic started to break globalisation and geostrategic competition has further fragmented it, [but] our core policy settings [haven’t changed],” he said.

Last year, a panel of national security experts commissioned by Nine Newspapers made the alarming suggestion that Australia could be at war with China within three years.

An invasion of Taiwan, the experts said, would be the likely flashpoint.

“This is not about 10 to 20 years, it’s really three years,” former Defence Department deputy secretary Peter Jennings told The Sydney Morning Herald. “The bulk of that 10 to 20 years will be a post-war environment where a new international order will prevail.”

Mr Shoebridge agreed the global situation was dangerous.

“I think we can already see a rising reaction to China just seeking to undercut everybody else’s manufacturing and own whole industries,” he said, contrasting the slow European reaction to Chinese solar panel and wind turbine imports to more rapid focus on EVs.

“The real area for judgement is will the speed of the reaction be unified enough and fast enough. It’s much harder to have a collective response to any issue because of the return of nationalism, and that is the land of opportunity for China.”

‘Grey area’

Beijing’s heavy hand in critical minerals markets like lithium and nickel – heavily subsidising every step of production for the highly polluting and energy-intensive industries – is another area where the line between economics and geopolitics is murky.

Individual nations define critical minerals differently. But mostly it’s applied to metals that exist in low, difficult-to-extract concentrations – often intermingled with toxic and radioactive materials – and are required for new technologies such as electric vehicles.

Effectively, non-Chinese producers are being forced to make long-term investment decisions to compete with the vast state power of China.

“That’s part of the reason why private capital is very apprehensive entering the space,” Adam Johnson, managing partner with Metis Endeavor, told the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

“It becomes a question of who’s going to take that risk. And that risk is ultimately being driven by geopolitics, which means oftentimes – from a private capital standpoint – you look to the government to provide solutions.”

The price of nickel has collapsed by more than 40 per cent in the past year due to a sudden surge in supply from Chinese-owned Indonesian producers, dropping from $43,000 a tonne to $25,000 a tonne.

At current prices, up to half of the world’s nickel mines are unprofitable.

“Indonesia’s supply surge puts global peers at risk,” S&P analysts said in a note last week, warning that the oversupply was likely a “structural change”.

“Global miner BHP says its nickel operations will not likely be profitable before the end of the decade and may mothball some operations. Several Australian miners have already announced they would suspend nickel operations … and the government has pledged support to the sector. Given China is a big foreign investor in Indonesia, and that nickel is classified as a critical mineral, the shift could exacerbate global geopolitical risks.”

David Whittle, adjunct professor of practice in resource engineering at Monash University, said China “certainly appears to act as a single player in the market and it does give them considerable strength”.

“They’ve been very strategic in taking very strong positions in a lot of the markets that we now call critical mineral markets,” he said. “The question of whether that’s fair is I guess a political question.”

But Prof Whittle said it was “kind of a grey area”.

“Look at Western Australia – WA as a state has made conditions pretty attractive for the production of iron ore and it absolutely dominates the bottom of the cost curve,” he said.

“What I do think is an issue is very often if you talk of production of minerals in China, the processing is very often done to very poor environmental standards. That provides an unlevel playing field, and we have to address that not by reducing our standards but somehow increasing the standards others have to comply with. One way is to track the provenance of these minerals and actually force companies to pay a premium.”

He suggested that “if you were able to level the playing fields in the environmental and also corruption areas I think there would be less to complain about in what China’s doing, they’re just being highly competitive”.

“Making China out to be the baddie in all cases I think is not correct,” he said.

How low will iron ore go?

The slowdown in China’s construction boom comes at precisely the worst time, with an oversupply likely to flood the market from next year as the massive Simandou mine in Africa starts exporting and delivering iron ore.

Last month, Yarra Capital predicted that iron ore prices faced a similar collapse to battery minerals lithium and nickel.

Dion Hershan, head of Australian equities at the well connected fund manager, highlighted parallels between iron ore and the nickel and lithium “carnage” during 2023.

He warned there was “obvious complacency” on iron ore “which, inconveniently, is Australia’s largest export ($144 billion in 2023) and speaks for 17 per cent of ASX 200 earnings (and 16 per cent of dividends)”.

“Demand for iron ore is stagnating,” he wrote.

“China – which represents 71 per cent of the global seaborne market – has a housing sector which is in a deep funk and an economy showing clear signs of maturity and saturation. Yet despite this malaise, iron ore supply is set to surge from 2025, with Africa’s Pilbara (the Simandou region) commencing production which — unless mitigated by supply cuts elsewhere – will push the market 5-10 per cent into surplus. As with nickel, China has an incentive to over-invest in the commodity, flood the market and drive down prices for one of their largest imports.”

He estimated this could result in a drop in the iron ore price of $US50 per tonne to around $US80, which would nearly halve the profits of BHP and Rio Tinto and Fortescue by nearly two thirds, and drag down the aggregate ASX 200 earnings by 10 per cent.

“Rather than waiting for history to actually repeat, investors would be wise to look through the current temporary earnings strength in iron ore stocks and reposition to avoid what could potentially be carnage,” Mr Hershan said.

Prof Whittle said he wouldn’t make too many comparisons between iron ore and the nickel and lithium woes, but added “the way you can compare events … is that it takes a long time to bring projects into production, it can be decades, and when they do come on even a 5 per cent change in supply can have quite a significant short-term impact on price”.

“The price elasticity of supply is very low in the short term,” he said.

“What that means is if the price goes low, the supply side doesn’t respond very fast. People get in when they can justify the investment but only get out once the price gets down or below their marginal cost of production.”

Business commentator Terry McCrann, writing in The Australian last week, said Australia’s three biggest minerals groups, BHP, Rio Tinto and Fortescue, were staring down “inevitable agony”.

The trio of companies recently announced gross profits adding up to $US44 billion ($68 billion), of which more than 80 per cent “came from digging up and shipping off, mostly to China, Pilbara iron ore”.

Even Beijing’s biggest ever cut to the benchmark mortgage interest rate to revive the property market failed to support prices, Reuters reported on Wednesday.

“Steel markets are weak and there is still little confidence in the economy,” Tomas Gutierrez, head of data at consultancy Kallanish Commodities, told Reuters.

“Beijing’s ability to engineer economic growth by traditional means is fading.”

Prof Whittle said even at a worryingly low price of $US80 per tonne the big three will still remain “very profitable” but “perhaps not with 70 or 80 per cent margins”.

“It will undoubtedly have downward pressure on prices – how long that will last, and whether it will get better or worse is anyone’s guess,” he said.

“It’s partly about how the major mining companies in Australia respond. I know they are absolutely thinking about this. At $US80 I’d be very surprised if they actually reduced their production below maximum capacity, but it will probably temper their decisions on investments in mine expansions and things like that.”

But Prof Whittle stressed that “at 80 bucks the Australian operations are still very profitable”.

“It might drive some costs out as well,” he said.

“We’ve found this in the past when the mines are making staggeringly high profits, you get a lot of fat in the business so actually a period of lower prices can have a cleansing effect.”

Prof Whittle estimated that Simandou coming online would add around 5 per cent to iron ore supply.

“Once it ramps up, what it will push out is the high-cost producers which are primarily Chinese,” he said.

“The Australian producers are way down the bottom of the cost curve, they will continue to produce at maximum capacity and I wouldn’t be surprised if they continue to increase capacity, unless the prices collapse very considerably.”

He added, “If I could predict the price of iron ore in three years’ time I wouldn’t have to work. People have been predicting the imminent collapse of the Chinese economy for the last 15 years. It’s always been just around the corner and maybe it is. But I don’t have a crystal ball on that.”