Australia’s fate relies on China throwing their own people under the bus

It’s bigger than Sydney and Melbourne yet you've likely never heard of it. This city and others in China decide our future.

ANALYSIS

In the 122 years since the individual colonies of Australia were federated into an independent nation, Australia has been consistently reliant on exports and the health of economy’s far beyond on our shores.

In the early decades of Australia’s independence, it was wool and grain heading to Britain. Since the turn of the new millennium, China has increasingly and quite swiftly become the economy Australia relies on most, with more than $150 billion of Australian exports flowing to the Middle Kingdom in 2022.

Yet even as tensions rise and Australia increasingly moves to prepare its armed forces for the possibility of war, the mutual economic reliance Beijing and Canberra share over one and other only grows deeper.

Prior to the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, China was the number two destination for Australia’s exports, with 14.5 per cent of the total flowing to the Middle Kingdom.

In 2022 things could scarcely be more different. Where in 2008 China was in the middle of a pack of more diversified export destinations, today 34 per cent of Australia’s total exports head to China, more than double its nearest rival, Japan.

With Australia’s economic fortunes now arguably even more deeply intertwined with Beijing’s than ever before, this raises some challenging questions about how our island nation will fare as the global economy slows and the possibility of a global recession rises.

Losing money to power industry

When assessing the outlook for Australia’s key bulk commodity exports to China such as iron ore and coking coal, things can’t be quantified in the same way as if they were destined for another more normal export market such as Japan or South Korea.

For example, 2022 was one of the worst years for the Chinese steel industry, with almost half of the largest producers reporting losses according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Yet instead of significantly cutting production more significantly in order to bring supply and demand into a more favourable equilibrium for profitability, the average Chinese steel mill spent much of 2022 losing money on their produce right out of the factory gate.

Seems the ramping up of Chinese steel production recently has been driven by factors other than the profit motive.

— David Scutt (@Scutty) March 29, 2023

Macquarie chart. pic.twitter.com/VKHMTtcswc

With steel the lifeblood of Chinese industry and much of the sector either directly owned or heavily influenced by the state, Beijing makes the trade off to maintain supplies, even if it’s done at a loss.

On the face of it, that’s pretty positive news for Australia. Rather than demand for key commodities such as iron ore and coking coal being moderated by normal market forces, those market forces are countered by Beijing effectively subsidising the steel industry.

But the more you begin to delve into the underlying Chinese demand for Australia’s commodities and the longer-term outlook, the more complex and messier it becomes.

Throwing everyday Chinese people under the bus

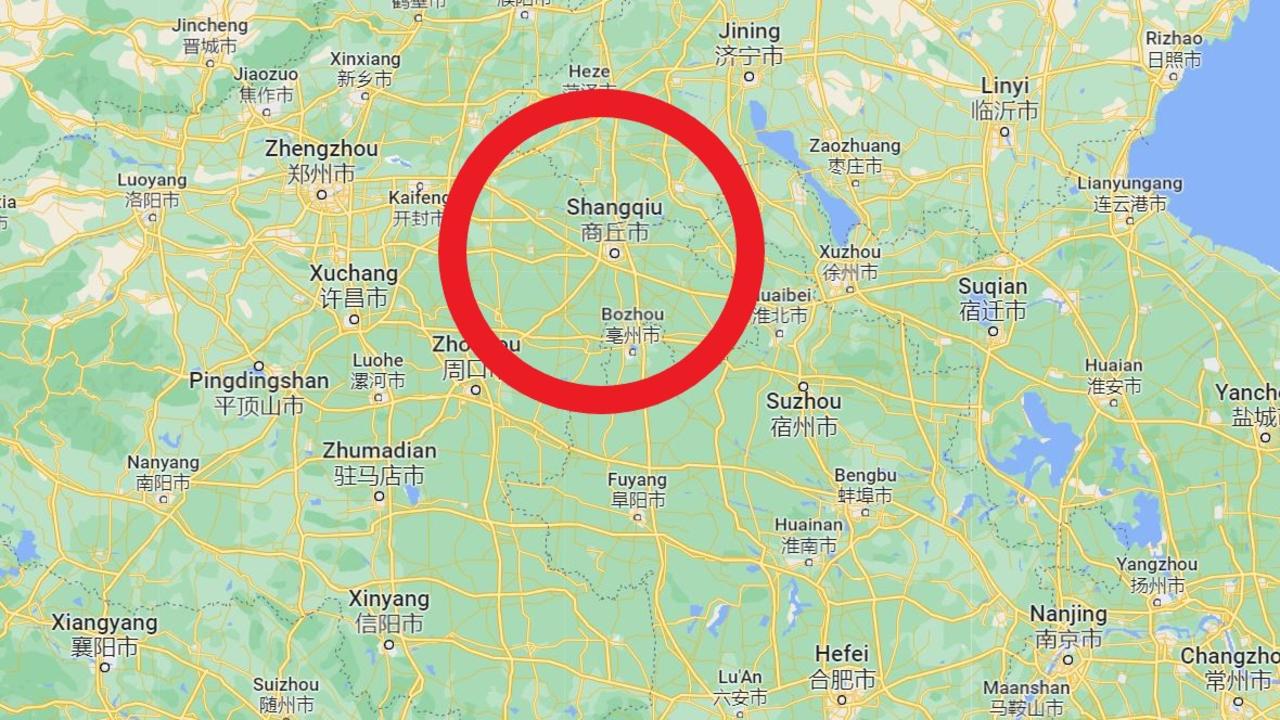

According to a recent analysis by the New York Times, the Chinese city of Shangqiu would be cutting spending on “education, health care, employment protection, and many other public services”, in order to dedicate funds to infrastructure construction.

To put the size of Shangqiu into perspective, the population in 2019 was 7.33 million or roughly 50 per cent more than Sydney or Melbourne.

Shangqiu joins more than 20 large Chinese cities which have cut key government services in order to keep spending on new infrastructure projects. One could say that the needs of the local populaces were being thrown under the bus in order for local governments to keep spending ever greater sums on construction, but unfortunately bus services in Shangqiu were cut because of a lack of funding.

In the mega city of Wuhan which became known across the world during the pandemic, seniors took to the streets to protest, after the local government cut monthly retirement payments which pay for healthcare.

To say that Chinese local governments had a debt problem would be an understatement. For example, in Shangqiu a full one third of all tax revenue is consumed by servicing debt. Yet instead of seeking a more sustainable fiscal path and ensuring basic services for the local populace, the local government has instead committed to over 700 key infrastructure and government projects.

On paper this is great for Australia in the short term, demand for steel making commodities will remain relatively robust even as the welfare of hundreds of millions of Chinese are sacrificed in order for local governments to keep building infrastructure with a highly questionable business case.

But in the longer term there is hardly a sign of health for China’s or Australia’s future economic prospects. At some point Chinese local government will need to resolve its debt crisis through one means or another.

What pathway may be taken remains unclear, we could see anything from an outright default on local government debt, to a bailout by the central government in Beijing in exchange for some major changes in how political and fiscal decisions are made in China.

Regardless of which path is ultimately chosen, the longer-term outlook for Chinese demand for Aussie steel making commodities is an increasingly challenging one amid a growing and unsustainable debt pile and a falling overall population.

A look by @TheEconomist at demographic comparison (using @UN data) between China (population peaking) and India (population overtaking China’s) pic.twitter.com/lxxIbbXSgz

— Liz Ann Sonders (@LizAnnSonders) January 11, 2023

For now at least the good times will continue to roll, the debt will continue to accrue and Beijing will underwrite the flow of loss making steel to fuel Chinese industry if necessary.

Ultimately, Australia needs a plan B to minimise its economic reliance on China, rather than become even more dependent on Beijing as geopolitical tensions continue to rise and Australia increasingly arms itself for war.

Perhaps now the deteriorating fiscal position of Chinese local government, ever worsening Chinese demographics and the geopolitical battlelines being drawn will drive a much-needed trip back to the drawing board.

Tarric Brooker is a freelance journalist and social commentator | @AvidCommentator