Why central banks do what they do to us

NEWS.com.au takes a look at what prompts interest rate movements, and how Australia's rates compare to the rest of the world.

Why central banks do what they do to us

NEWS.com.au takes a look at what prompts interest rate movements, and how Australia’s rates compare to the rest of the world.

The Reserve Bank of Australia meets next week to announce its latest interest rate decision. The bank is most likely to keep the official cash rate unchanged at 7.25 per cent, but economists haven’t fully ruled out a movement either way.

The slowing economy points to the RBA holding rates steady, but inflation is higher than the bank's target band. The RBA will announced its decision on Tuesday afternoon.

Why do rates move?

Central banks raise or cut interest rates as a way to keep an economy on track.

A key factor in their decision is keeping inflation - or the rate of prices rises - under control. Central banks generally have to keep inflation within a target band. This is done in an effort to promote slow and steady economic growth, and avoid boom and bust cycles. High inflation is often an indication that an economy is growing too quickly, while low inflation points to a sluggish economy.

Raising rates generally slows spending as people have to direct more of their money into higher housing costs. Cutting rates has the opposite effect, freeing up more money for people to spend and stimulating the economy.

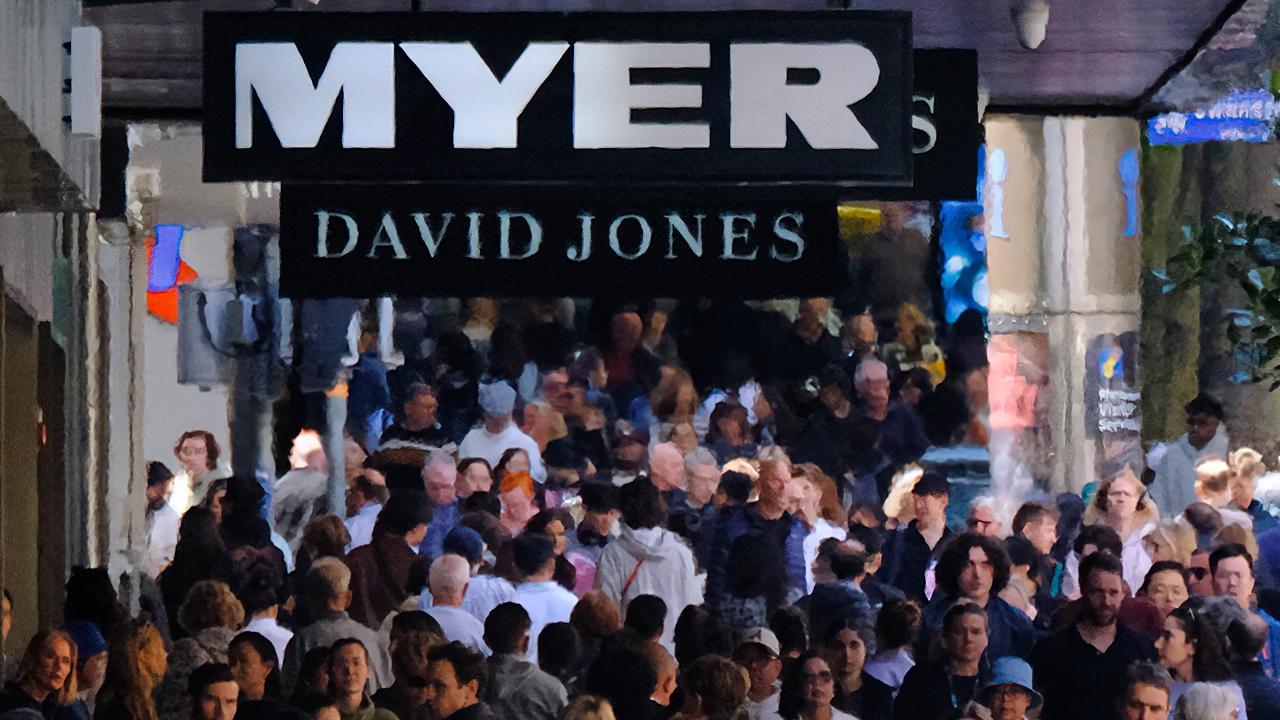

While important, inflation is not the be-all and end-all for central banks. They also need to look at the broader economic picture. Things like business and consumer confidence levels, retail spending, whether there are more or fewer buildings going up, unemployment rates, job vacancies, all point to the general health of an economy.

What central banks want to avoid is stagflation. This is where an economy has to battle high inflation alongside a slowing economy and rising unemployment.

So, who’s doing what?

The rate-cutters

THE UNITED STATES

The US Federal Reserve has cut rates seven times since September last year in an effort to breathe some life into the country’s flagging economy.

The latest 25 basis point cut, announced this week, dropped the Fed’s key interest rate to 2 per cent. The central bank hinted it had not ruled out further cuts this year.

The US economy has teetered on the brink of recession this year, following a share market meltdown in January as well as a credit crisis sparked by lenders losing billions of dollars on bad loans.

Figures out rhis week show the US staved off recession in the first quarter of this year, with the economy limping into positive territory and posting growth of 0.6 per cent. This means the US isn’t technically in a recession, which is defined as two consecutive quarters of an economy going backwards.

BANK OF ENGLAND

The Bank of England has cut its key interest rate three times since December. The latest 25 basis point drop was made in April, cutting the rate to 5 per cent.

The cut came despite the country’s 2.5 per cent inflation breaching the bank’s 2 per cent target.

The BOE cited broader concerns about the slowing economy as the reason for the cut, prompting some analysts to tip there will be more cuts to come this year.

The rate-holders

EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK

The European Central Bank has kept interest rates steady at 4 per cent since June last year. The stand-still is despite the fact the region’s 3.2 per cent inflation rate is well outside its target band of 2 per cent and is the highest level since the euro was launched in 1999.

NEW ZEALAND

At 8.25 per cent, New Zealand’s key interest rate is the second highest in the developed world (behind Iceland).

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand has not moved rates since July last year, after several years of regular rises. The country’s inflation rate of 3.4 per cent is outside the central bank’s target of 1 to 3 per cent. Economists are tipping the RBNZ could cut rates by the end of the year – but only if all signs point to inflation being firmly under control.

JAPAN

Japan’s central bank left its key interest rate unchanged at 0.5 per cent when it met at the end of last month.

Japan has had the opposite problem to many other economies in recent years, battling deflation rather than price increases. Deflation is a sustained fall in prices. It’s seen as a negative for an economy because it usually leads to companies dropping production levels, which has a flow on effect on wages, demand and investments.

Japan is now back in inflationary growth zone, with the current 1.2 per cent inflation rate a decade high for the country.

The rate-hiker

ICELAND

Iceland’s 15.5 per cent official interest rate is the result of drastic rate hikes – one of 1.25 per cent at an emergency meeting in March – made in an effort to tame inflation.

The country’s 8.7 per cent inflation rate is well above the bank’s 2.5 per cent target.