More consumer woes as Covid-19 lockdown in Shanghai clog supply

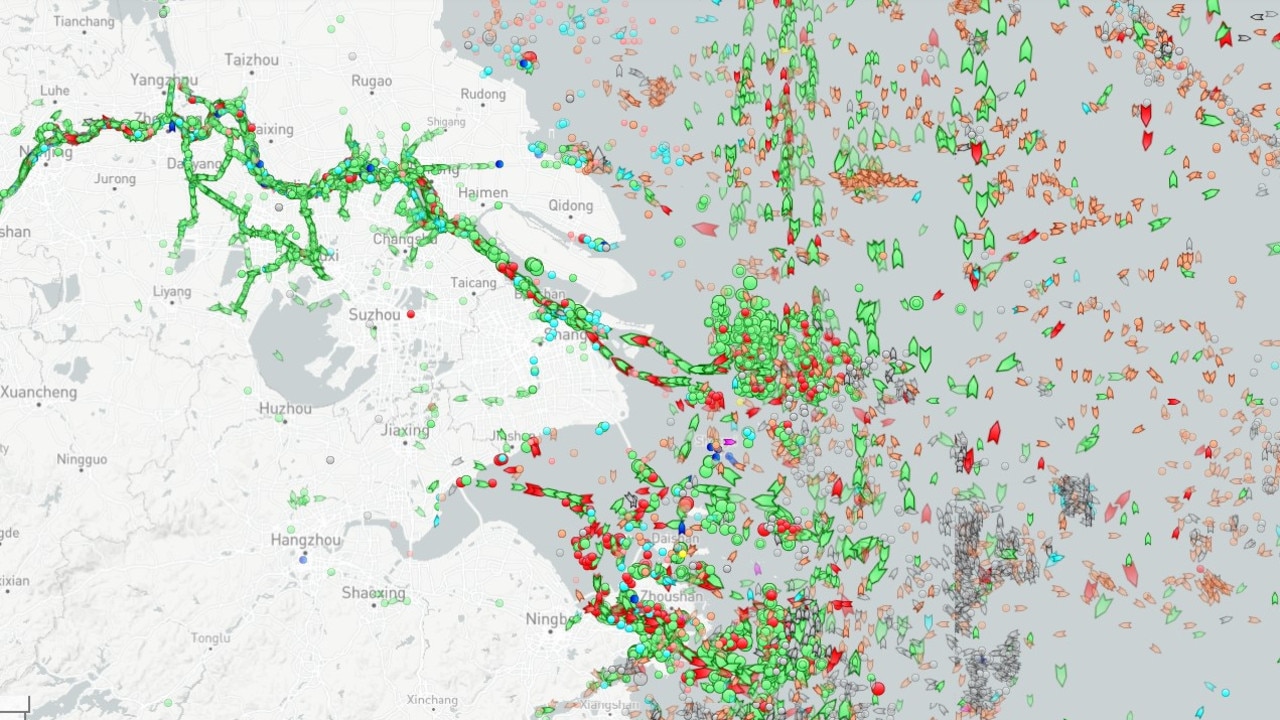

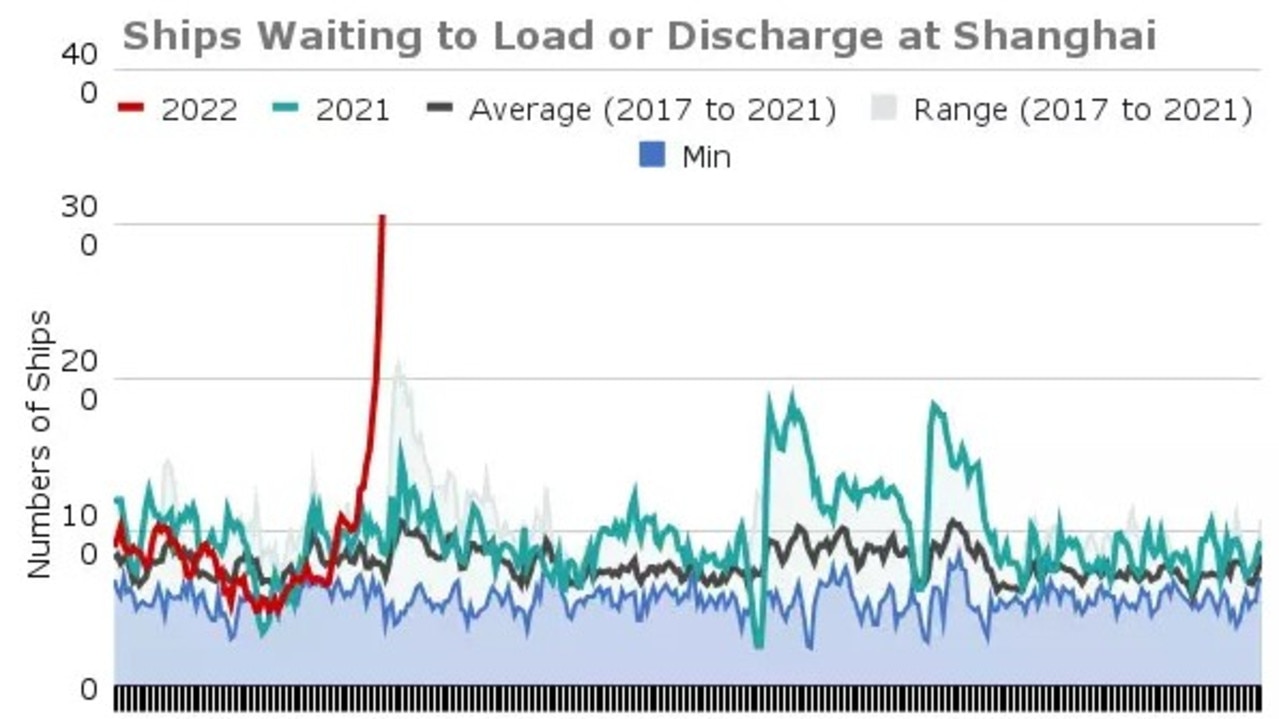

The number of cargo ships waiting outside the port of Shanghai has quintupled due to challenges arising from the city’s lockdown.

Australian consumers may face higher prices, longer shipping times, and scarce supply as Shanghai’s lockdown cripples the world’s busiest port.

Reports say that rigid testing protocols, a workforce stifled by Covid-19 infections, and health checkpoints are throwing sand in the gears of Shanghai’s port, the busiest port in the world according to the World Shipping Council.

ANZ research senior economist Bansi Madhavani said the Shanghai lockdown is “a great setback to global supply chains already stretched by geopolitical tensions”.

“Ancillary activities such as warehousing and staffing will be affected, causing delays,” he said.

China is currently experiencing a spread of Covid-19 on a scale not seen since its original outbreak in Wuhan at the start of 2020, and it is this time centred in Shanghai.

The nation today reported 3,316 new cases.

The Chinese government has imposed a strict lockdown and mandatory testing system on the city of 26.3 million according to a 2019 count. That is greater than the entire population of Australia at 25.9 million according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ latest estimate.

VesselsValue, a global logistics data provider, said that the number of ships on standby at the port of Shanghai had increased almost fivefold in three weeks.

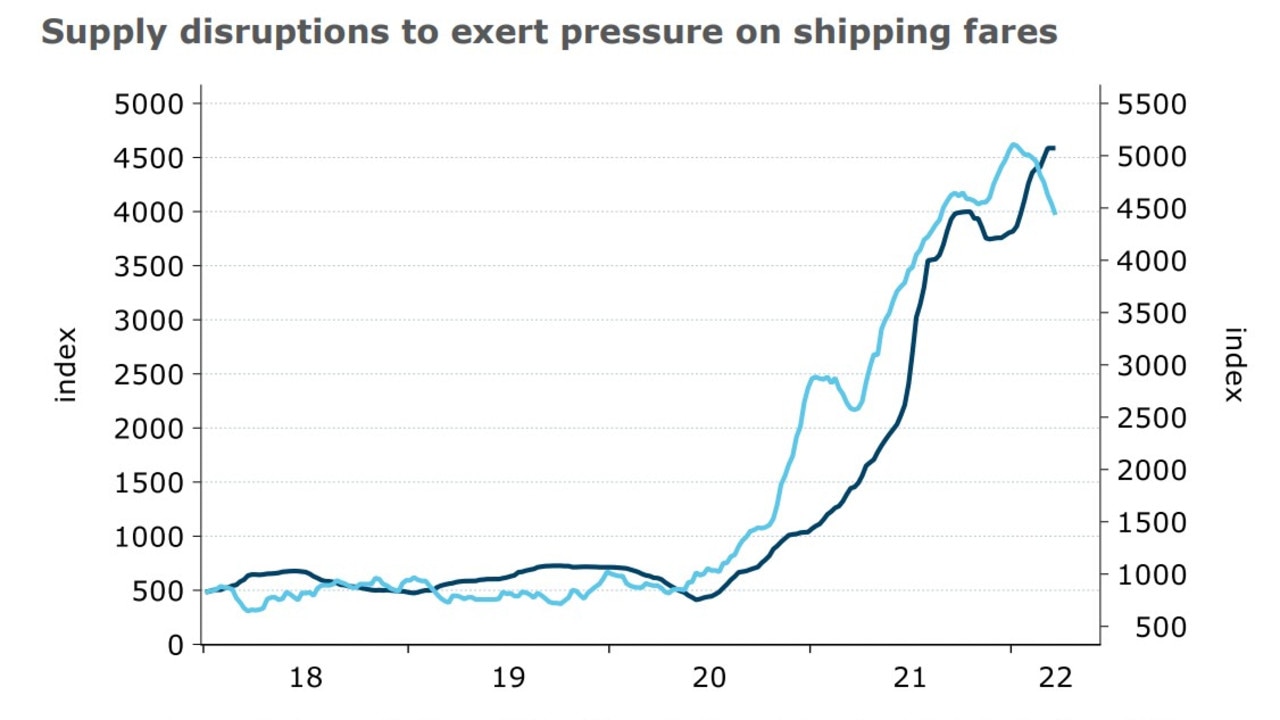

This development piles misery on an already out-of-sorts global supply chain. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has rerouted global shipping and trade, and sent the price of fuel into a tailspin. In the meantime, global demand for shipping has not abated and the price of shipping has continued to climb and is now almost five times that before the start of the pandemic.

Shanghai is a critical port in the global supply chain. Shanghai handled 43.5 million cargo containers in 2020, more than triple the throughput of Rotterdam, Netherlands, the busiest port outside Asia.

Supply chain woes

This adds misery to weary consumers who have already seen shocks to the global supply chain not seen in decades.

The pandemic has brought into spotlight numerous flaws in the global supply chain, with one problem precipitating another and that, another.

At the start of the pandemic, people retreated into their homes and turned to the internet for their shopping, fingers itching from boredom and wallets thicker from government stimulus and not booking that annual family holiday.

Money had also never been cheaper, with central banks lowering rates to near-zero.

This would ordinarily have stretched supply lines thin but the situation was exacerbated by the fact many manufacturers could not ramp back up to meet the unexpected rebound in demand. Many had instead expected the inverse — that consumers would tighten their pursestrings like the did in the Global Financial Crisis a decade prior.

However, consumer demand picked back up. This naturally meant that everything else had to start back up again, and fast.

But this is easier said than done. Many modern manufacturing processes are just one part in a complex web of value-adding activities. For example, computer chips are incredibly delicate to manufacture and many fabrication centres had shuttered their doors at the start of the pandemic. They can take weeks to start back up, assuming that their input channels are humming along smoothly. Prices still have not stabilised.

This had knock-on effects not just to computer parts, but to modern cars which need chips, which then knocked on to the second-hand car market and car rental markets.

On top of these disturbances, the cargo shipping industry — the plumbing of modern global trade — was struggling to keep up in the new environment, with unexpected demand patterns and scattered, constantly changing Covid-19 restrictions at different ports.

Early predictions said that global shipping would normalise by the end of 2022, but stresses such as the Shanghai lockdown are most likely going to push back that horizon.

Dynamic zero Covid

Meanhwhile, Beijing insists its zero-Covid policy of hard lockdowns, mass testing and lengthy quarantines has averted fatalities and the public health crises that have engulfed much of the rest of the world.

But some have cast doubt on official figures in a nation whose vast elderly population has a low vaccination rate. Shanghai health officials noted Sunday that less than two-thirds of residents over 60 had received two Covid jabs and less than 40 per cent had received a booster.

Unverified social media posts have also claimed unreported deaths — typically before being scrubbed from the internet. Hong Kong, meanwhile, has attributed nearly 9,000 deaths to Covid-19 since the Omicron variant surged there in January.

The Shanghai Municipal Health Commission on Tuesday said the seven victims were aged between 60 and 101, and all suffered from underlying conditions such as heart disease and diabetes.

The patients “became severely ill after admission to hospital, and died after ineffective rescue efforts, with the direct cause of death being underlying diseases”, the commission said.

It also reported more than 20,000 new Covid cases, the vast majority asymptomatic.

Many of Shanghai’s 25 million residents have been confined to their homes since March as daily caseloads have topped 25,000 — a modest figure by global standards but virtually unheard of in China.

Many inhabitants have flooded social media with complaints of food shortages, spartan quarantine conditions and heavy-handed enforcement, circulating footage of rare protests faster than government censors can delete them.

The country’s zero-tolerance approach to Covid had largely slowed new cases to a trickle after the virus first emerged in the central Chinese city of Wuhan in late 2019.

But officials have scrambled in recent weeks to contain cases spanning multiple regions, largely driven by the fast-spreading Omicron variant.