‘Largest windfall in history’: Major cash rate fact Boomers conveniently ignore

Bring up today’s cash rate and Boomers will inevitably gripe about the 17 per cent rate of the 1980s. But they’re forgetting one major thing.

Since the RBA began raising interest rates back in May last year, the issue of interest rates has rarely been out of the headlines.

Not since the days of 17 per cent mortgage rates in the late 1980s and early 1990s has monetary policy been such a lightning rod of an issue.

But there is another side to the headlines detailing how much the latest rate rise is going to cost the average mortgage holder – interest rates are eventually cut.

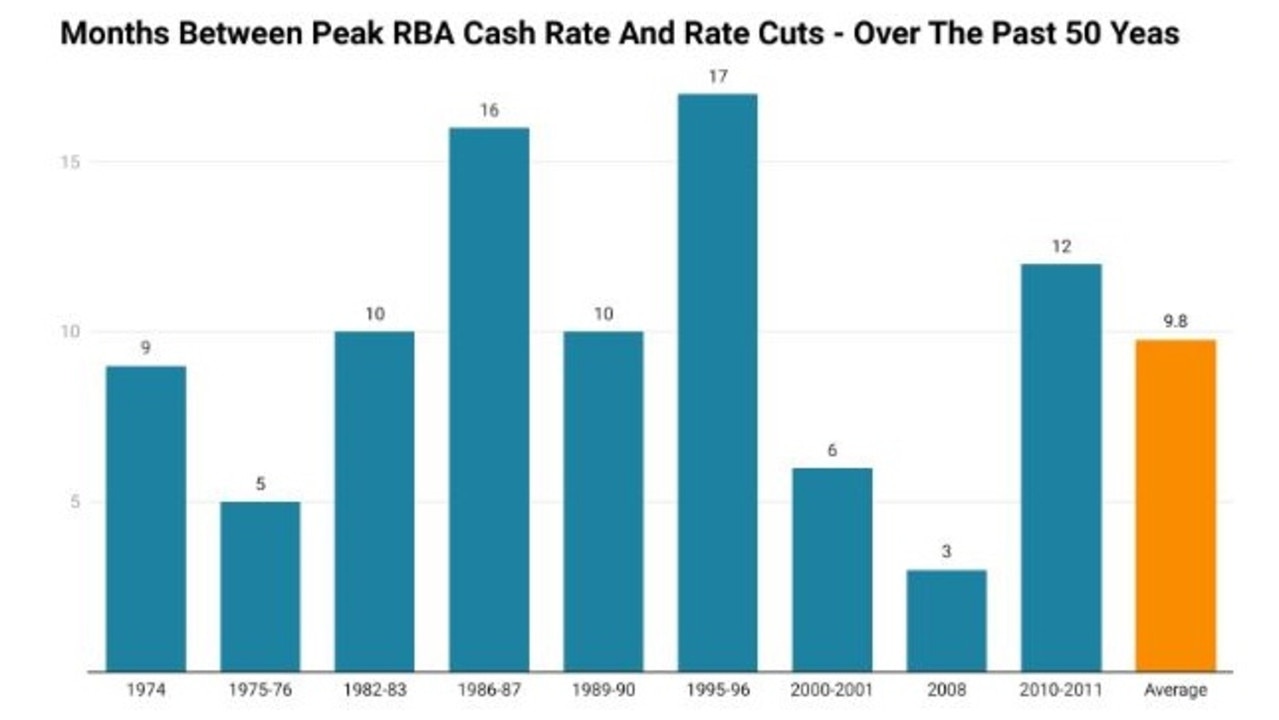

Over the past 50 years, once the RBA cash rate reaches its peak for the cycle, interest rates are cut an average 9.8 months later.

The longest period the cash rate spent at its peak for an individual cycle was 17 months in 1995-1996, while the shortest time was in 2008, when it spent just three months at its peak.

It is not the rate cuts that generally persist in living memory, but instead the period of high interest rates that lives on for decades to come. Which is unfortunate in some ways, as it overlooks the enormous windfalls mortgage-holding households have enjoyed from interest rates being cut.

Following the peak in the RBA cash rate at 17 per cent in 1990, the cash rate was slashed again and again, until three and a half years later it sat at just 4.75 per cent. This rate cut cycle marked the largest windfall for mortgage-holding households from monetary policy in Australia’s history.

Based on the reduction in the standard variable mortgage rate for owner occupiers, mortgage repayments fell by 44.5 per cent during this rate cut cycle. Prior to this, the largest reduction in mortgage repayments in a single rate cut cycle since comparable records began in 1959 was 13.4 per cent, between 1983 and 1985.

From 1990 onwards, Australian mortgage-holders saw windfall after windfall from rate cut cycles, with each cycle after this period being larger than any other seen in records prior to 1990.

In the 32 years between the first cut in interest rates from their all-time high and the RBA raising rates in May of last year, Australians became accustomed to rates trending in only one direction over a protracted period – down.

But it wasn’t always like this. Between 1968 and 1990, mortgage rates were in an uptrend which left many borrowers concerned about when the next rate rise would inevitably come. During this period the average standard variable mortgage rate for owner occupiers rose more than threefold, from 5.38 per cent to its ultimate all time high of 17 per cent.

Case study

In order to provide a bit of perspective rather than just headline numbers, here is a case study to explore that details how much of a windfall lower rates have provided for different households over time.

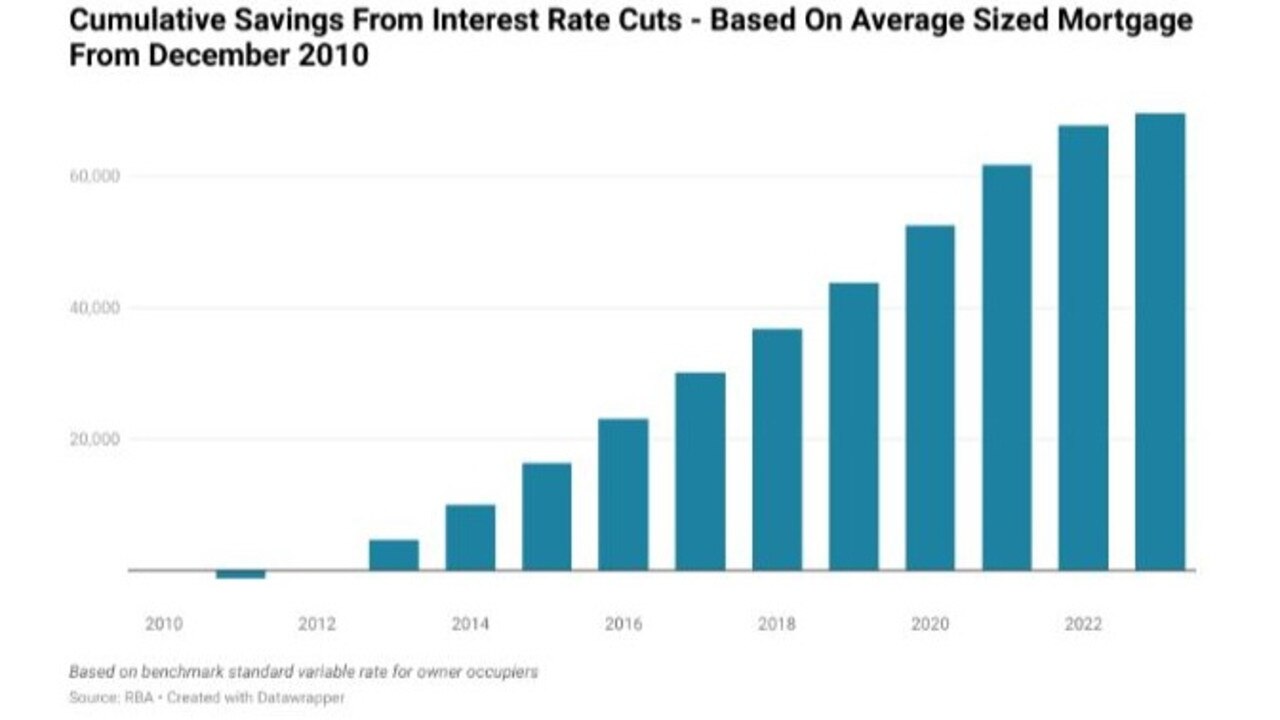

For example, for a household which purchased a home in December 2010 with an average-sized mortgage of a bit over $364,000, this household would have cumulatively saved over $69,000 over the past 13 years due to interest rates being cut. Its worth noting that this is based on the benchmark average standard variable rate for owner occupiers.

If this hypothetical household refinanced to a fixed-rate loan during the pandemic, the savings would be even greater. Based on refinancing to the average three-year fixed rate mortgage at the end of 2020, the cumulative savings compared with their initial mortgage rate would rise to over $93,000 by the end of this year.

The advent of low fixed rate mortgages following the RBA’s Term Funding Facility providing up to $200 billion in funding to the banks at 0.25 per cent interest (later 0.1 per cent) was a boon for mortgage-holders more broadly who took advantage of the opportunity to lock in low rates.

At its peak in early 2022, almost 40 per cent of Australian mortgages were on fixed rates, a huge departure from a banking system that has generally been defined by 85 to 95 per cent of mortgages being on variable rates throughout most of its modern history.

The balance

In the history of Australia, monetary policy has given and it has taken away. Amid the largest and fastest relative rise in mortgage rates in our nation’s history, the focus is currently very much on the taking away.

But over the past 33 years in aggregate since interest rates hit their all-time high, monetary policy has overwhelmingly given more than it has taken from mortgage holders.

While it is often the challenges that we face that shape our collective memories more than the windfalls that we experience, the impact of these windfalls should not be forgotten.

Tarric Brooker is a freelance journalist and social commentator | @AvidCommentator