Worrying trend in jobs figures

For decades, one chart has told us all we need to know about the health of the Australia economy. But it hides a growing problem.

Australia’s unemployment rate is much too high. It may be 5 per cent. That may be one of the lowest rates we’ve seen in a decade. But it should still be much lower.

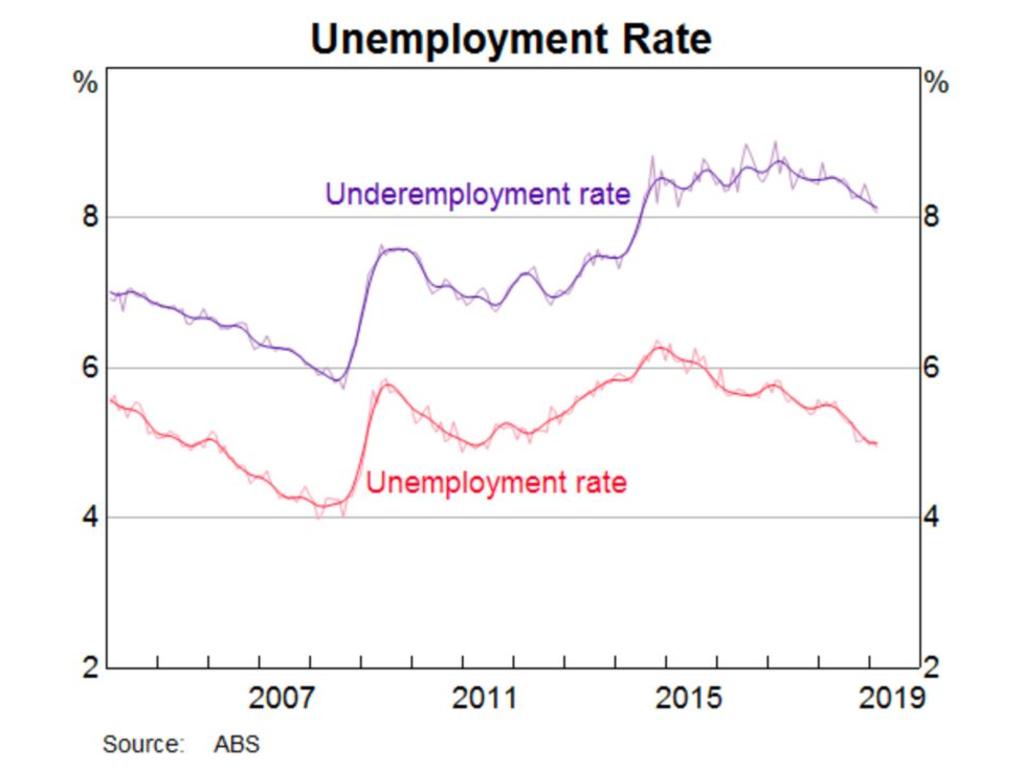

Look at the next graph. It used to be the case that if unemployment was 5 per cent, that meant underemployment would only be 6.5 to 7 per cent. These days we have unemployment of 5 per cent and underemployment of more than 8 per cent.

What this means is that the unemployment rate no longer tells us the full story about our economy. In fact, it can be obscuring some pretty important facts.

Australia’s wage growth is terrible, despite what looks like low unemployment. This is considered to be a mystery. But the mystery clears up if you look at the underemployment rate.

It’s easy these days to do a little bit of work while you look for a job. You can work in the gig economy driving for Uber, or work for Airtasker, or do lots of similar sorts of jobs. If you do, you get counted as employed. But you’re not necessarily employed to your potential.

The officials of the Reserve Bank of Australia keep describing “tension” between the poor performance of the economy and the impressive performance of the labour market. But the truth is this — there is no tension. The labour market is slack. Loads of people want more work. The economy is not delivering for them.

PHILLIPS CURVE

In the economy there is a relationship between inflation (which we want to be low) and employment (which we want to be high). If we push employment too low, we get an uncomfortable level of inflation. So there is a level of unemployment that represents “full employment”. (The technical term for this is the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment.) Some estimates in the past have put full employment at 5 per cent.

In Australia, and in other countries around the world, inflation has been low for a long time, despite the employment statistics telling us that we are close to “full employment”. This is seen as a mystery.

Once again, the mystery disappears if you accept that 5 per cent unemployment no longer means what it used to. Five per cent unemployment these days might be equivalent to 6 or 7 per cent unemployment a few decades ago.

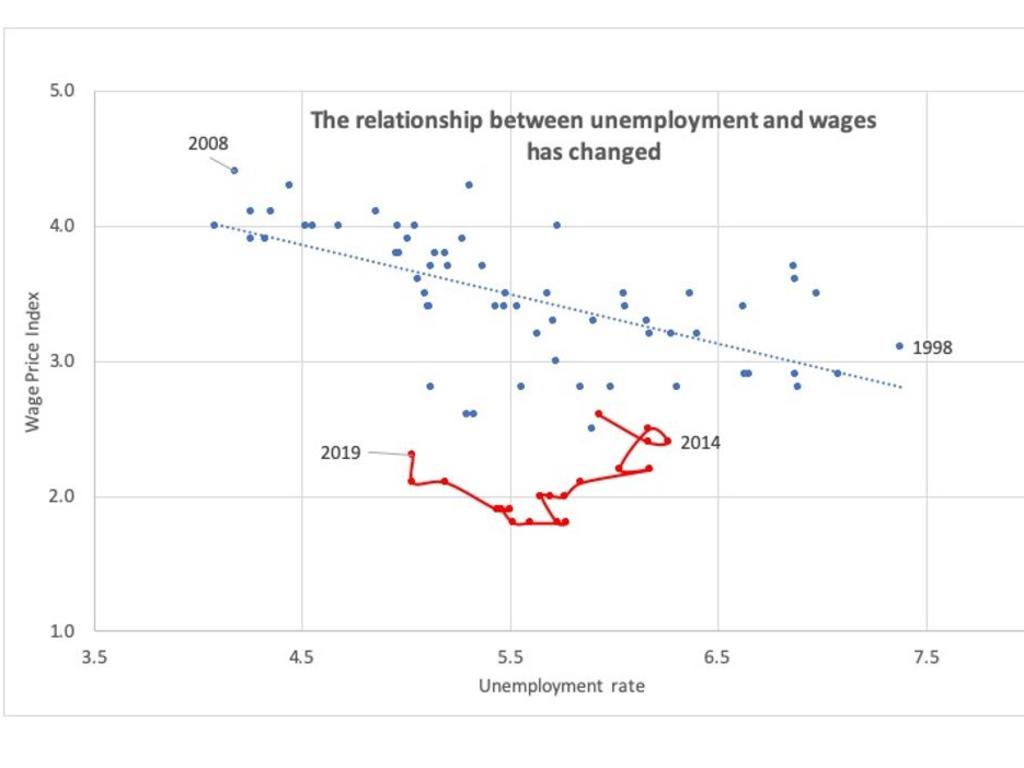

The relationship between unemployment and wages growth can be depicted on a graph. Each dot in the graph below represents unemployment and wages growth at a point in time. The graph shows that since about 2014, we have moved to a new paradigm where we are getting previously unseen combinations of unemployment and wages growth, as depicted in the linked red dots.

Under the old 1998-2014 trend (blue dotted line on the graph) an unemployment rate of 5 per cent would have meant wages growth of over 3.5 per cent.

‘WE SHOULD BE RAGING’

If we want to get wages growth up, and if the Reserve Bank wants to get inflation back into its target range, we need to be willing to aim for a much lower unemployment rate than 5 per cent.

Australia could probably comfortably have an unemployment rate of three-point-something per cent. And we should probably be raging about the fact nobody shows willingness to get there.

To get the unemployment rate lower, there are a few paths:

• We could stimulate the economy more using fiscal policy. That might involve lower taxes and higher spending. The Keynesian approach.

• We could stimulate the economy using monetary policy. This looks risky at the moment because lower interest rates are largely behind the amazing run-up in household debt.

• We could set out on an ambitious program of micro-economic reform and deregulation. This would potentially be costly too. After all, part of the reason the unemployment rate looks low is that the labour market is flexible enough that people can get a bit of gig economy work whenever they want.

My own opinion is fiscal policy is the answer. And to see why that might make sense, we can look at America.

LAND OF THE THREE

As mentioned above, the phenomenon of low unemployment, low wages growth and low inflation is global. Not just Australia. That’s good news because it means we can learn from overseas. What happened in America is fascinating.

When US President Donald Trump handed out huge tax cuts he did not set out to provide a stimulus that would drive the unemployment rate down. What Trump did was not because he cared about workers. But it seems to have helped them.

US unemployment fell to 3.7 per cent. US average hourly earnings have risen by 3.2 per cent, which is healthy, but not enough to make inflation dangerously high. The consumer price index in the USA is up only 1.9 per cent.

This is not to say we should emulate Trump’s tax cuts. His went to people and companies who really didn’t need them. Australia could provide fiscal stimulus in very different ways — building infrastructure, for example. The key to giving ourselves freedom to do so would be to admit that keeping the budget in surplus is not as important as keeping people in work. In fact, the more people in work and the faster Australia’s nominal GDP grows, the easier it is to pay back government debt.

The only reason not to continually strive to push unemployment down is to avoid setting off damaging inflation. The risk of damaging inflation right now is negligible. We should not be afraid to abandon our old ideas about what counted as full employment. Australia should aim for an unemployment rate that starts with a three, and we’ll all be better off.

Jason Murphy is an economist. He writes the blog Thomas the Think Engine. Continue the conversation @jasemurphy