Why your five and 10 cent coins may soon disappear

There are more of these in Australia than people – but 2020 could spell the end for this everyday household object after demand has halved.

Even before the pandemic, the Royal Australian Mint was gently nudging the five cent piece into its grave.

Demand for coins had halved in the last five years, the Mint boss said as 2020 dawned, and he expected Australia’s smallest coins – the echidna-emblazoned five and the 10 cent piece with its lyrebird – to “die naturally” soon enough.

The pandemic is now likely to dramatically shorten the natural life course of Australia’s smallest silver coins.

RELATED: Graph shows what is killing Aussie malls

RELATED: Economic crash will devastate us all

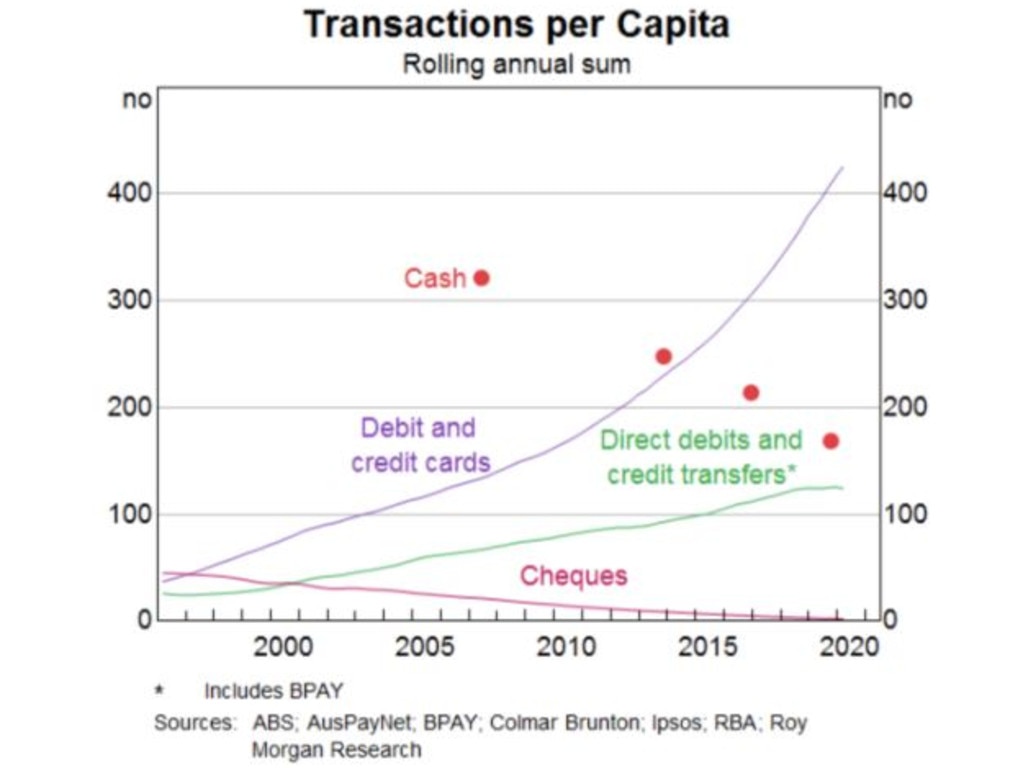

The RBA tracks the use of cash in Australia, and they have never seen it fall so fast as it has in recent months.

“ATM withdrawals in April were down 30 per cent from the month before and over 40 per cent lower than 12 months earlier,” RBA Assistant Governor Michele Bullock said in June.

Not only are people concerned about touching cash that has gone through other people’s hands, but the kind of shopping trips where you might use cash are fewer and fewer.

RELATED: Secret message buried in Aussie coin

Use of cash will never snap back to where it was, the RBA predicts. Ms Bullock expects “permanent shifts in behaviour as some people maintain the new ways of doing things.”

That means the future for coins is to become increasingly ornamental.

Darryl Stephen runs vending machine company CC Royal. His industry is still closely associated with cash.

“We offer all ways of payment, so for example a customer will come in and buy a machine off us. We offer a coin changer, a note reader and a cashless system and eight times out of 10 they will take all three. That’s to ensure they maximise their sales.”

Vending machines have been forced to keep using coins even as consumers themselves are less likely to use them. When customers started using notes to pay, you might have assumed machines needed less space for coins. The reverse is true. To make change for customers paying with larger denomination notes, vending machines have been re-engineered to have larger and larger coin reservoirs.

“Coins going in dropped, coins going out went up,” said Mr Stephen. “Some people put $50 notes in to buy a product for $5.”

But during the COVID-19 pandemic things have slowed dramatically. “We are probably 70 to 80 per cent down on business at the moment,” Mr Stephen said. “We are not the only ones.”

That means much less coin usage. This trend is likely to be amplified by changes in technology – Mr Stephen also sees cashless systems “on the rise”.

In the USA they have a coin shortage, and the US Treasury Secretary has even been encouraging people to look down the back to their couches.

If you have extra coins at home, please use them to make purchases— or deposit them at the bank or exchange them for cash. Help get coins moving! 🇺🇸

— Steven Mnuchin (@stevenmnuchin1) August 11, 2020

But America has a different attitude to coins than Australia. They still have their one cent coin – the penny – where we got rid of ours in 1992. Americans also use cash far more often. In Australia in 2020, it’s been different. Demand for coins has been virtually zero, according to comments by the head of the Royal Australian Mint. While American business needs more coins circulating, Australia needs fewer.

The end of the five cent coin will not be a huge loss to the Royal Australian Mint. It is made of nickel and copper, and the price of both those metals has surged in recent months. The value of the metal in a five cent coin is worth more than three cents, so there’s very little profit left over after minting them and shipping them.

The Mint has always made profit for the government by minting coins and selling them. They call that profit seigniorage. But as coins become less popular, seigniorage has been falling. In their most recent annual report it fell 47 per cent below budget, to just $26 million. This financial year will likely look even worse.

It would be astonishing if the Mint – which can literally make money – lost money. But if demand for coins fell low enough it would theoretically be possible. One solution would be to make the coins out of steel instead, like New Zealand. Coins there are lighter, smaller and made of cheaper materials. Another solution is to stop producing the coins with the smallest seigniorage, in which case it would be time to say goodbye to the five cent piece. And maybe this is the best time to do it.

Jason Murphy is an economist | @jasemurphy. He is the author of the book Incentivology.