What’s wrong with Malcolm Turnbull’s innovation obsession

IT’S Malcolm Turnbull’s favourite buzzword, but a US policy expert says his obsession with this popular ideology may do more harm than good.

IT’S Malcolm Turnbull’s favourite buzzword.

But his obsession with innovation is a mistake, according to a US policy expert.

Politicians across the world are falling for it, says Lee Vinsel. And Australia’s Prime Minister is one of the most focused.

“I don’t think I’ve seen a platform as consolidated and put together as in Turnbull’s statement,” said the assistant professor from New Jersey’s Stevens Institute of Technology.

“There’s a lot of the same in the US, but it’s been put together over decades.”

The idea sounds dynamic and progressive: a politician’s dream. Yet the danger of concentrating so closely on the new is that you overlook the importance of what already exists.

“The current discussion of innovation tends to put a lot of emphasis on new things and the role they play in life, but most things are quite old,” says Vinsel.

Roads, power grids, transport — we often need to maintain or improve what we have already, rather than generate new things.

As politicians in every state vie to come up with big-ticket ideas for fast trains, light rail and new traffic systems, it’s a timely warning.

CRUMBLING INFRASTRUCTURE

Vinsel doesn’t think we should give up innovation entirely, but says it’s about balance. His aim is to create a critical discussion and stop us overvaluing the concept, which has become the dominant ideology of our time.

“When you hear about technology today, it’s all about how new things are going to save you. In the US, we have crumbling infrastructure and water systems full of lead. We have a train system so degraded the train can’t go at full speed because it will break the rail.

“We hear big promises around new projects. It might be state-led, Google Glass or smart homes. Then they don’t come through and you have aggravated consumers.

“Innovation might be important, but we need to pay attention to the basic things.”

The cycle of successive governments looking to put their innovative mark on society feeds into the problem, says Vinsel.

The National Broadband Network screw-ups are a “great example of not carrying through on basic plans.”

This age of innovation began in the 1970s, which was also the start of an era of growing inequality, says Vinsel. “A lot of innovation just ends up putting money into the pockets of people who already have money.”

We can see this inequality highlighted in Mr Turnbull’s unpopular election promise of tax cuts for big businesses, which Labor capitalised upon during the campaign.

ALIENATING ORDINARY PEOPLE

In July, West Australian Liberal MP Andrew Hastie slammed the Coalition’s innovation-focused campaign strategy for alienating ordinary people.

He said there was a disconnect between the policies and everyday Australians concerned about their family’s future.

In the US election campaign, both sides are talking innovation, but Donald Trump is succeeding with a certain section of the public because he “speaks to the maintainer portion left behind by the economy.”

We shouldn’t assume that focusing on innovation will necessarily produce the best results in education, and should remember that invention is the creation of new ideas, while innovation just means fusing them into society.

“It’s a shiny thing,” says Vinsel. “It’s hard for politicians to avoid.”

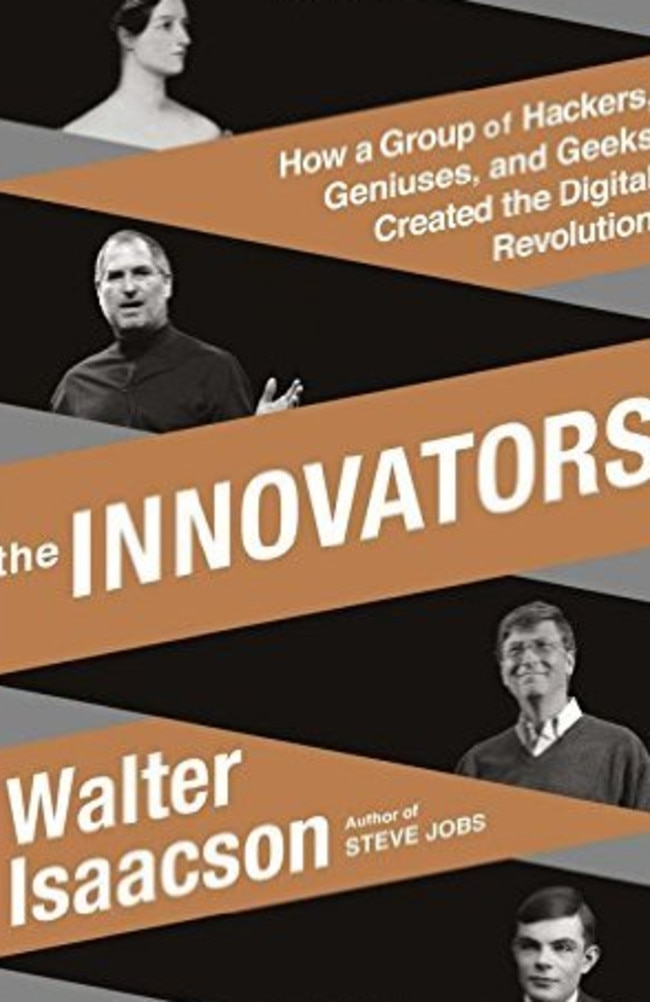

Vinsel suggests a more honest reworking of Walter Isaacson’s popular 2014 book The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution.

He’d call it: The Maintainers: How a Group of Bureaucrats, Standards Engineers, and Introverts Made Digital Infrastructures That Kind of Work Most of the Time.

Hear Lee Vinsel’s talk, The Innovation Fetish, at The Festival of Dangerous Ideas at Sydney Opera House on 4 September at 10.45am, tickets from $33.