‘We’ve never been asked’: Uncomfortable truth about immigration debate

In 1996, John Howard sat down for a radio interview where he made a telling statement that no political leader would say today.

In October 1996, Prime Minister John Howard sat down in the Sydney studio of 2UE talkback host John Laws for a lengthy discussion about the one subject on everyone’s mind — immigration.

A month earlier, Pauline Hanson set off a national firestorm when the newly elected Member for Oxley declared in her maiden speech to parliament that the country was “in danger of being swamped by Asians” who “have their own culture and religion, form ghettos and do not assimilate”.

While her remark is shocking by today’s standards, at the time, polls suggested many Australians agreed with her.

Mr Howard insisted it was “inaccurate to say that we are being swamped”.

“We will never go back in this country to having a discriminatory immigration policy based on race,” he told Laws. “That is gone and I think it is morally, politically and economically in this country’s interest that it be gone.”

But the then-PM stressed he agreed “with the reality that we need to have a debate about things like immigration”, warning of the danger if “people feel shut out of the immigration debate”.

“The greatest complaint I have from people, and it’s been going on for some years, is, ‘Look, we don’t feel that we’ve ever, sort of, been consulted about the level of immigration, we don’t feel that we’ve ever been asked, we don’t feel that you lot down there have ever listened, we have this idea that you’ve all sort of got together and decided it’s too hard for us to handle,’” he said.

“People have felt as though it’s a bottled-up thing.”

A few years later, Mr Howard would oversee the start of Australia’s 21st century “Big Australia” boom, culminating in record post-Covid immigration of more than one million people under Labor — and now an election fight over which party will bring the numbers back under control.

For many Australians in 2025, Mr Howard’s words ring even truer nearly three decades later, “We don’t feel we’ve ever been asked.”

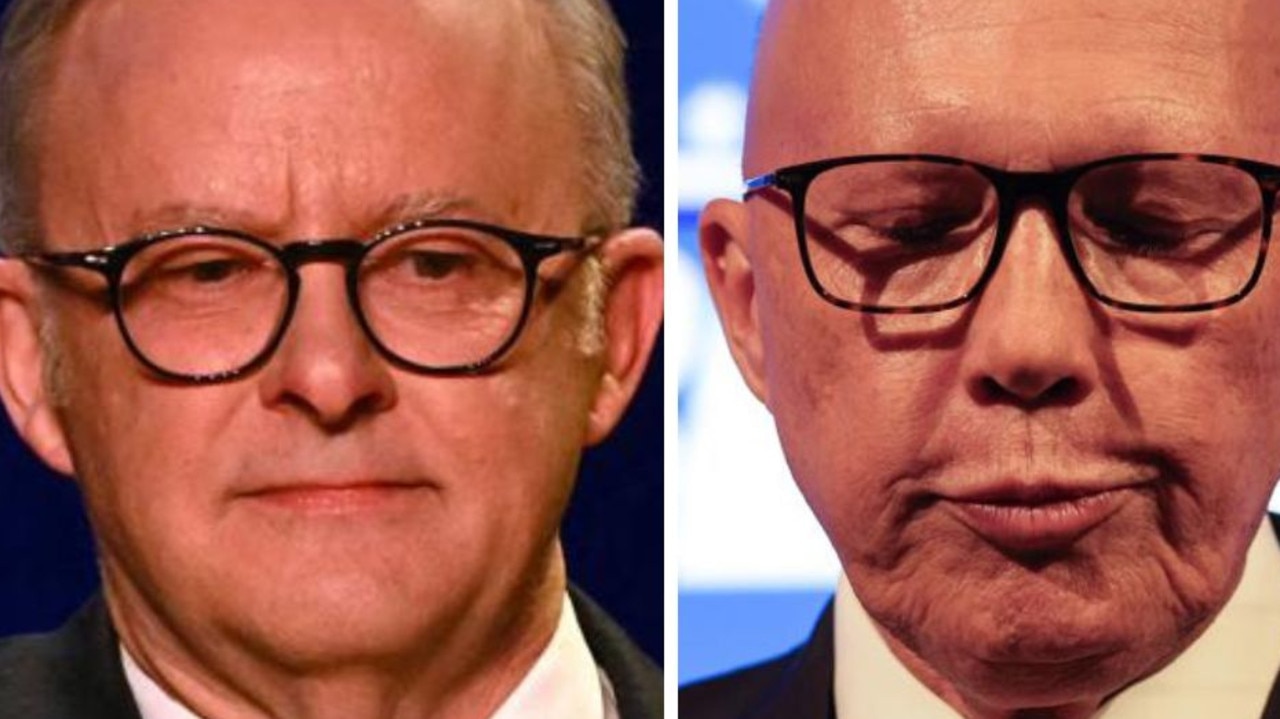

But as Prime Minister Anthony Albanese faces far-right hecklers on the campaign trail, and migrant communities report rising racist rhetoric, there are echoes of Mr Howard’s other warning to Laws.

“In the process of taking the cork out of the bottle we’ve got to be absolutely certain that the ratbags and the bigots … that they get treated as they deserve to be treated, and that is with contempt,” he said.

Changing face of Australia

Today nearly one in three people in Australia was born overseas, the highest proportion since before Federation.

More than half of the population now was either born overseas or has a parent born overseas.

“In 1901, four of Australia’s top five countries of birth were in Europe and one was in Asia,” the ABS states.

“By 2021, one was in Europe and three were in Asia. China was in the top five at Federation due to the attraction of the Gold Rush and a series of internal crises in China from 1849 and 1887. The proportion of people born in China started to decline as the Gold Rush ended and the White Australia policy was enacted.”

The growth of the Indian diaspora, in particular, has been explosive.

Between 2013 and 2023, Australia’s Indian-born population more than doubled from 378,480 to 845,800, overtaking Chinese-born residents — who went from 432,400 to 644,760 — to become the second-largest migrant community making up 3.2 per cent of the total population.

“Since 2001, the main sources of Australia’s overseas born population growth have been from those born in India and China,” the ABS states.

“The growth in migrants from these countries is likely due to Australia’s strong labour market and university sector as well as Australia’s geographic proximity.”

In the same 10-year period, the number of residents born in England fell from more than one million to 961,570, while those born in Italy — the only other country in the top 10 to decline — fell from 200,670 to 158,990 — reflecting the ageing of the post-World War II migration wave.

“Key reasons for the fall in European-born populations include moving away from a discriminatory immigration system and assisted migration programs in the 1970s and the European Union’s freedom of movement laws, which have made it relatively easier and cheaper for Europeans to access the labour market across Europe,” according to the ABS.

“In addition, Europe’s ageing population will lower the number of people who are likely to migrate. An ageing European-born population in Australia has also contributed to the decline in these overseas born populations. For an overseas born population to remain large, constant high levels of migrants from the home country are needed to replace deaths — this is because the children of overseas born people are counted as Australian born.”

In 2023-24, the top countries for migrant arrivals were India and China, driven by record numbers of international students on temporary visas.

Under the permanent migration program — which only accounts for about 40 per cent of the net overseas migration figure as most granted visas are already in the country — citizens from India, Afghanistan and Pakistan saw the strongest growth last year.

Between 2021-22 and 2023-24, 115,317 Indian nationals were granted permanent visas, nearly double the 63,982 permanent migrants from China.

‘White extinction anxiety’

Public concerns about housing affordability and cost-of-living pressures mask a more uncomfortable reality.

The rapid shift in the ethnic makeup of Australia’s new arrivals means any opposition to immigration is, unavoidably, tied up in questions of race, religion and culture.

“Anti-immigration discourse has become entrenched in mainstream politics across many Western countries,” Deakin University’s Samantha Schneider writes for news.com.au.

“We see it in the United States, since the 2024 election of Donald Trump, and in European countries where political parties such as Alternative for Germany (AfD) and France’s National Rally (RN) have platformed anti-immigration policies and sentiments as central to their electoral appeals. Contemporary mainstream conservative anti-immigrant rhetoric includes the scapegoating of immigrants for high rates of youth gang crime, terrorism, and the current housing crises facing various Western countries.”

These debates in Australia are “nothing new” and have “periodically characterised previous election cycles”.

“Many ordinary Australians are able simultaneously to feel positive about multiculturalism and migrant communities while expressing fears around the perceived impact of population growth resources, for example, in relation to housing, health care and urban amenity,” Ms Schneider writes.

“But for some extreme and radical right social movements in Australia, as elsewhere in the world, concerns around immigration are linked to resource distribution and scarcity.

“These ideas have long been weaponised to support fantasies of racial homogeneity and purity and rigid hierarchies of social value and power in society. Extreme and radical right social movements deploy anti-immigration sentiment as a central plank of their efforts to drive social polarisation, create fear and anxiety about social change, and accelerate the collapse of Australian society to usher in an exclusivist ethno-nationalist state of white Australians.”

Ms Schneider said these extreme elements “elevate the concept of an ultranationalist ‘white nation’ while simultaneously claiming this imagined ‘nation’ is under constant siege and attack from ethnic, religious and racial others, producing ‘white extinction anxiety’”.

‘Screaming out for less’

One of the most prominent voices among the new online Australian right is Jordan Knight, a former One Nation staffer turned anti-immigration influencer.

Mr Knight has amassed tens of thousands of young followers across his Migration Watch social media channels.

He first began speaking out on the issue for “selfish” reasons, after seeing rents fall during Covid border closures and the subsequent resurgence of migration.

“The major concerns for me obviously are housing, homelessness is rising,” he said.

“But it’s not even just homelessness, it’s quality of life. If your rent is going up faster than you can afford it, you’re forced into worse living situations. This is a standards-of-living issue. This brings with it all sorts of second-order consequences [for infrastructure]. If we’re growing our population by 500,000 people, 700,000 people a year, but we’re not growing our roads, our hospital services, we’re not growing out housing market, then they’re all going to be under immense strain. What we’re seeing is a rapid deterioration of living standards in Australia.”

Mr Knight believes immigration is a “civilisational and existential question”.

“Why are the elites doubling down on mass immigration when most Australians, most westerners, are screaming out for less and less?” he said.

“Partly I believe it’s ideological. I think the people who want more immigration are those who are so wealthy that they’re typically removed from the effects of immigration. They might not see the impacts on roads, hospitals. Another part of it is people simply make money from it.”

And then there’s the other elephant in the room — are governments simply importing voters?

A Brookings Institute study in the US last year found immigrant voters, even those who identified as socially conservative, leaned heavily Democratic.

“Labor hasn’t admitted that they’re bringing in migrants because migrants will vote for Labor,” Mr Knight said.

“But if you’re in the Labor Party, and you’re seeing that your political power will grow on the back of a high migration scheme, you’re probably not going to be incentivised to stop it. [Electorates with large migrant voting blocs represent] a Balkanisation of our politics and it just shows that mass immigration really does impact democracy in Australia.”

According to Mr Knight, Australians deserve a proper national debate on the role of immigration “but our leaders aren’t listening, they don’t want to have that conversation”.

“Australians should [decide], but we’ve never had a proper discussion or debate or a referendum on its role in Australia,” he said.

“People want cultural compatibility when it comes to immigration, but that’s just never discussed. The worst thing that we’ve ever done as a country is these technocratic leaders have treated immigration as nothing more than a spreadsheet, nothing more than just numbers and words on a page, and losing a certain selectiveness.”

He sees rising tensions “because people feel hard done by”.

“Especially if you see, for example, ongoing protests in Australian cities,” he said.

“If we see clashes between different groups on our streets [from] two countries that we actually have no idea or care about really, then Australians are going to stop and question, like, OK how is this benefiting me? My rent has gone up, my wage hasn’t moved in 20 years, my town where I grew up is changing rapidly and I may have to move because it’s so expensive, and I can’t even take my kids into the city because there’s a massive protest now. I was told immigration, multiculturalism was good for me, and actually I’m poorer, my country is less cohesive and my living standards are getting destroyed. So what in this is good for me?”

What do Aussies want?

Public opinion polls, when they have been conducted, have generally found Australians favour lower immigration.

A 2023 survey for Nine Newspapers found 62 per cent of voters felt the intake was too high, and successive polls by The Australian Population Research Institute (TAPRI) have put the figure at 60-80 per cent.

The Scanlon Foundation’s long-running Mapping Social Cohesion study last year found the share of people who think immigration is too high had increased to 49 per cent, up from 41 per cent pre-Covid.

But the findings suggested this was largely linked to concerns economic concerns like housing and cost-of-living, with 85 per cent agreeing “multiculturalism has been good for Australia”.

And of those who said immigration was too high, only 7 per cent said immigration was the most important problem facing Australia, compared with 48 per cent who cited economic issues and 15 per cent pointing to housing shortages and affordability.

Overall just 4 per cent thought immigration was the biggest problem facing Australia.

Monash University Emeritus Professor Andrew Markus, who pioneered the Scanlon Index of Social Cohesion in 2007, said it was clear from the numbers that immigration was not the “major issue” for most Australians.

“Now the economy is tied in with immigration as well, but, top-of-mind issue? The Scanlon survey is not finding that,” he said.

“You also need to get a broader perspective, if you look at the long term … it’s not unusual to get 40-45 per cent, that would probably be the normal benchmark for immigration being too high.”

Prof Markus argued that whatever their views, “for a lot of people” immigration amounted to “so, what?” — having little real impact on their day-to-day life.

“So it’s the sort of question where you’re never going to get 80 per cent of people saying it’s wonderful,” he said.

Notably, the Scanlon Foundation survey found concerns about more than four in five (83 per cent) people were opposed to Australia rejecting migrants on the basis of their ethnicity or race, while a similar proportion (79 per cent) were opposed to rejecting on the basis of religion.

“[In the 1980s there was] a majority negative view towards immigration,” said Prof Markus.

“There were a number of polls then, and that got caught up with the Asian issue, which was highly politicised, because Australia came out of the White Australia policy not much earlier than ‘88. Probably in real terms we didn’t really move away from that policy until the late ‘70s with Vietnamese migration. That was probably the first major break within that. We’ve really moved away from that now. It’s not so much about ethnicity or religion, it’s much more about the economic impact.”

TAPRI founder Bob Birrell has been researching public attitudes on immigration since the 1980s.

His most recent poll found just 11 per cent wanted the current high numbers to continue, while overall only 27 per cent said Australia needs more people. More than three quarters believed adding more people pushes up the cost of housing.

Like Prof Markus, Mr Birrell says it’s unclear whether immigration is a vote changer, despite the increasing noise on the campaign trail.

“Immigration [in Australia] has not become a telling political issue as is recently the case in Britain and much of western Europe because our migration flow, though much higher than people would like, has not been accompanied by high levels of illegal migration, open community conflict or terrorism,” he said.

“In other words, people don’t like the Australian migration outcomes but it’s not high enough on the political attention scale to change votes.”

‘They don’t like diversity’

In direct contrast to the Scanlon Foundation findings, TAPRI’s poll uncovered significant pushback to the core tenets of Australia’s non-discriminatory migration policies — a shift which Mr Birrell attributes to rising community tensions in the wake of the Israel-Gaza war.

Fifty-nine per cent of respondents said selection policy “should include a migrant’s ability to fit into the Australian community”, while only 28 per cent said “religion, values and way of life should not affect selection decisions”.

“The big change is the effect of community-based opposition to Israel representing the Palestinian community and expressing their concerns in anti-Semitic language,” Mr Birrell said.

“That’s frightening to people who regard themselves as one Australia. That is the priority, that we should stick together as one nation and not be breaking down into [ethnic factions]. That’s very strongly held in the majority of the electorate, and the same attitudes are held by a big majority of European and English-speaking migrants as well. They’re just as critical of multiculturalism as the Australian-born. They simply don’t like diversity, even though they’re a part of the diversity. Multiculturalism in a sense for them is dead. They aspire primarily to be Australians.”

Mr Birrell said it was striking that voters were now comfortable speaking about migration in these terms.

“The upsurge in community-based agitation in relation to the Palestinian issue does seem to have created a new sense of concern,” he said.

“The majority of people were quite willing to say that they didn’t agree with the fundamental core of multiculturalism, which is above all we must accept diversity regardless of people’s origins.”

Prof Markus disagreed.

“One of the things I look for is that indication of heightened hostility, and there isn’t much evidence of that,” he said.

“It’s not like the 1980s when there was a big debate about Asian immigration, and there were times when [there was a debate] about immigrations from Africa, in the 1990s and early 2000s, again we don’t have that.”

But he warned “Islamophobia, anti-Semitism, those sort of issues are important”.

“Conflicts in the university environment I think are very significant,” he said. “The level of fear that we have in sections of our Australian community, that’s certainly not normative. Obviously, if you talk to people in the Jewish community, they would say that it’s pretty much unprecedented.”

Dr Abul Rizvi, former deputy secretary of the Immigration Department, warned any change to Australia’s non-discriminatory migration program would only further threaten social cohesion.

“I guess the question would be, how would you do that?” he said.

“Trump wanted a Muslim ban, for example — is that what we’re talking about? He’s now said, well we’re going to ban migrants from certain countries — is that what we’re talking about? The definition of what you would do remains vague to me. Unless someone could sit down and say this is what I mean, it’s all just wafting in the wind. I hate to use the phrase dog-whistling but that’s what it seems like to me.”

Dr Rizvi said America and Europe, with their low fertility rates, faced a bleak future if they “move down that path”.

“The fact is over the next 20, 30, 40 years, the competition for young skilled migrants of any colour will keep intensifying,” he said.

“People are kidding themselves if they think it will go away. China will enter the immigration market, they’ll have to. They’re not going to sit back and say we’re going to halve our population.”