Two words that shoulder the burden of our economy

Australia’s economy is in the hands of a system made famous in an advert 20 years ago, now the future is looking very dicey.

In the early 2000s the Commonwealth Bank ran an advertising campaign encouraging homeowners to tap the equity they had in their loans to fund all manner of consumption.

In arguably the most famous TV advertisement, a neighbour extols the virtues of ‘Equity Mate’ to his friend, suggesting that he could use a home equity withdrawal to take his wife on holiday.

In the two decades since the Equity Mate campaign first hit our television screens, the concept of home equity withdrawals has evolved from an interesting side note in academic finance papers to a major driver of the economy.

In the 12 months to the end of June 2021, Australians withdrew $93 billion in home equity from their mortgages for all sorts of reasons, from providing capital to a family-owned small business to funding general household consumption.

At the time, home equity withdrawals amounted to roughly 4.65 per cent of GDP.

The history of ‘Equity Mate’

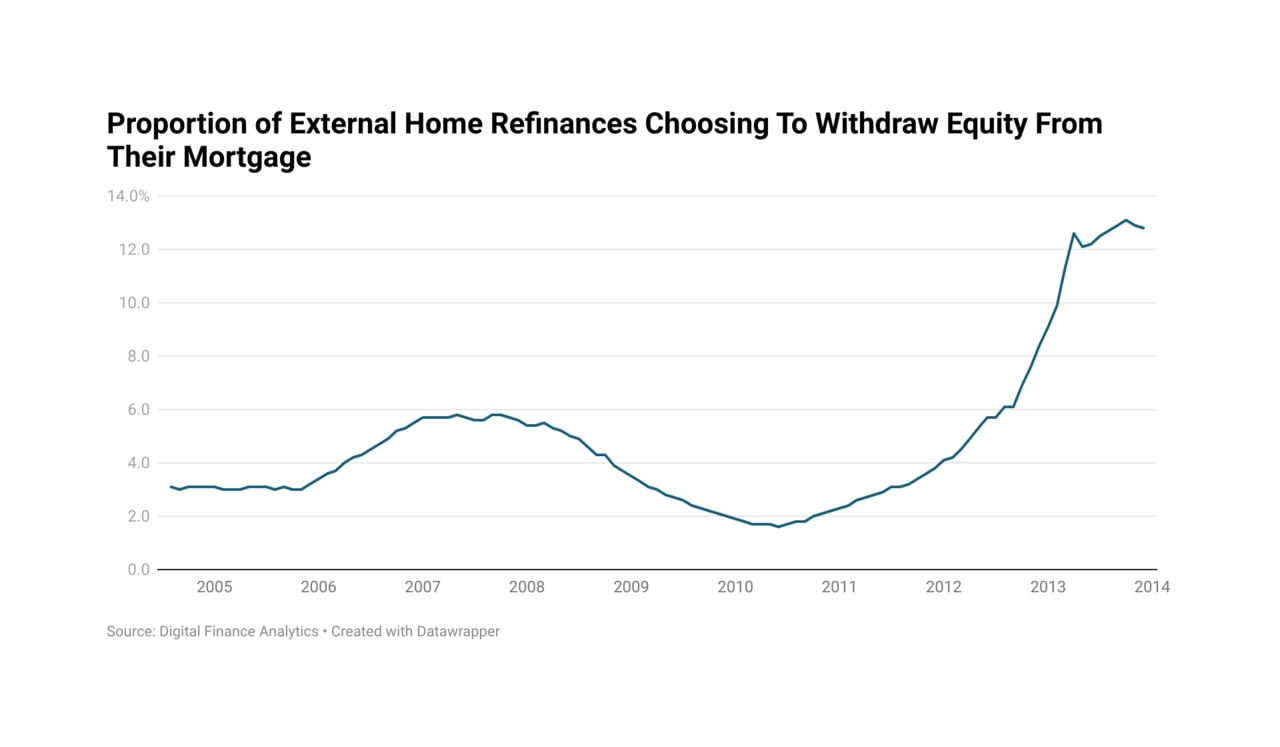

Research firm Digital Finance Analytics has been chronicling the history of home equity withdrawals in its monthly data since 2004.

At the start of the data series roughly 3 per cent of borrowers externally refinancing their mortgage chose to withdraw equity at that time.

Externally refinancing is when a borrower takes out a new loan with a new bank and their existing loan is concluded with their existing lender.

Over time, demand for home equity withdrawals ebbed and flowed as the economy saw booms and slowdowns, property price falls and property price rises.

In the first decade of the data, which covers through to the end of 2013, the proportion of external refinancers withdrawing equity hit as low as 1.6 per cent in May 2010 and as high as 13.1 per cent in October of 2013.

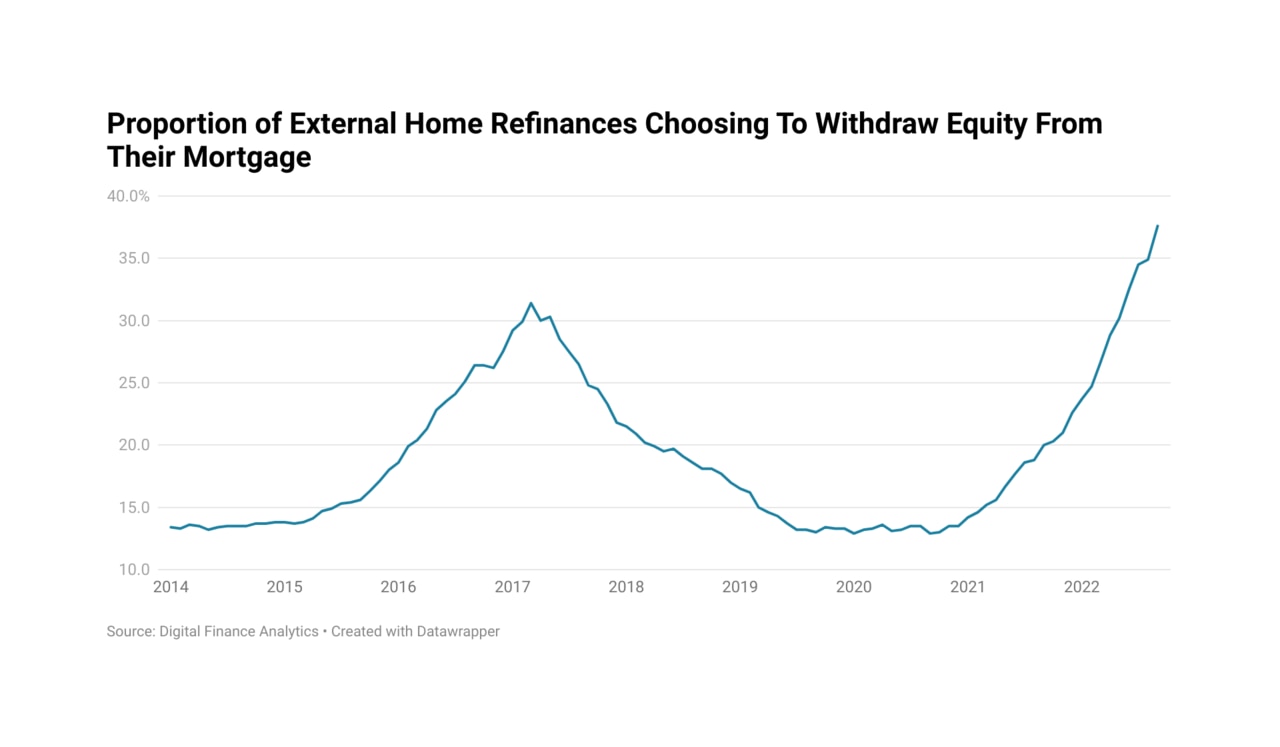

At this point you may be wondering why the data set was split into two separate halves. In short, because the rise seen in the second half of the data is so large relative to levels in the first half of the graph.

Amid the stagnating real household disposable income that defined much of the mid- to late-2010s, the allure of funding consumption or investment with home equity withdrawals seemingly took on a new level.

Between January 2015 and the peak in March of 2017, the proportion of external refinancers choosing to withdraw equity rose by 131 per cent to 31.4 per cent.

Over the next two years the proportion of external refinancers looking to withdraw equity fell by more than half to just 12.9 per cent, arguably due to the fall in house prices during that period.

The run up in housing prices that followed the pandemic would change all of that. From the lows seen in September 2020, the proportion of refinancers withdrawing home equity rose by 191 per cent to well over a third (37.6 per cent).

A road well travelled

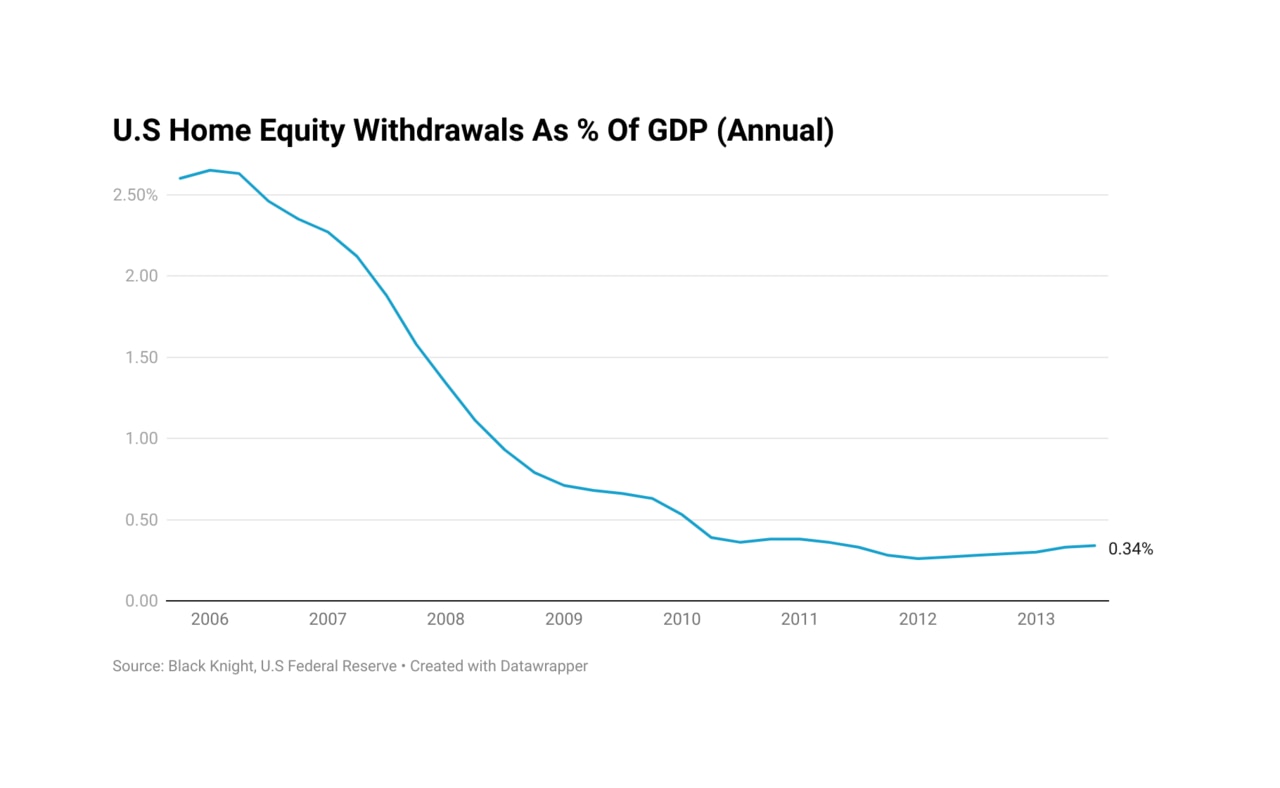

In the months and years following the outbreak of the Global Financial Crisis, American households were criticised for “using their homes as an ATM” and funding consumption with home equity withdrawals.

During this period the United States became a global cautionary tale for its high level of household debt and the associated systemic risk.

In the first quarter of 2006, home equity withdrawals in the US peaked at 2.65 per cent of American GDP. This puts them at 57 per cent of the level that Australia’s withdrawals were in June 2021, relative to the size of the nation’s respective economies.

Over the next six years in the US, home equity withdrawals as percentage of GDP fell by over 90 per cent, providing yet another headwind to the crisis-hit US economy.

If Australia were to hypothetically see home equity withdrawals fall by a similar proportion of GDP over the coming years, there would be a hole in household cash balances and consumption to the tune of 4.19 per cent of GDP.

To put this figure into perspective, during the GFC the Rudd government provided $21.4 billion - that’s 1.7 per cent of GDP - in cash payments to pensioners, families and workers earning less than $80,000 a year.

The wind at the economy’s back

For years, home equity withdrawals have been a major force supporting activity within the Australian economy, at times making a larger contribution than any single pre-Covid stimulus measure or even entire budget deficits recorded since World War II.

The big question now is can they continue to support the economy, even as the equity pool required to fund them is slowly evaporating amid falling inflation-adjusted household incomes and rising interest rates.

In the short term at least, the answer on paper appears to be yes. Despite housing prices falling in most markets in recent months, the proportion of households withdrawing equity from their homes has only continued to rise.

Since the start of the year the proportion of households withdrawing equity while externally refinancing has risen from 22.6 per cent to 37.5 per cent.

In short, there is a lot of equity there to be tapped, over $7 trillion in aggregate.

While in the US prudence and tightened lending brought home equity withdrawals down from its highs, the question is whether or not there will be the stomach for that sort of action from regulators here in Australia.

And there is no sign of households tempering their appetite for Equity Mate.

Far more rests on the outcome of this single economic factor than many would like to think, but ultimately the future of Equity Mate could be a deciding factor in the future of the nation’s economy.