Fresh superannuation shake-up flagged after intergenerational report

Australians can expect major changes to encourage them to spend their superannuation amid fears retirees aren’t using their savings as they should be.

New incentives could be introduced to encourage retirees to spend their super savings, Treasurer Jim Chalmers has foreshadowed in a major address.

The change is designed to address a problem called “longevity risk” – the issue retirees face when they are forced to hedge their superannuation savings against the length of their life.

Due to the risk of outliving your savings, retirees die on average with approximately a quarter of their superannuation savings still sitting in their account.

Australia’s super scheme has also been criticised for being used as a means to bequest savings onto family members, rather than to fund retirements.

The potential changes, set to be considered before the end of the year, would incentivise retirees to be less cautious about their spending through the final years of their life.

“I do think that there is a big problem, a big challenge, for us to address,” Treasurer Jim Chalmers told the National Press Club.

“Super is one of the big national advantages that we have, but it's not perfect. We need to keep working to try to perfect it.”

“People are more frugal than they need to be, they’re more conservative than they probably want to be.”

The foreshadowed superannuation changes follow the release of the sixth Intergenerational Report (IGR), which revealed the nation faces a growing budget black hole due to slower economic growth, higher spending, chronic deficits and debt, and lower population growth, and shows

In a speech to the National Press Club void of any new government policy commitments, Dr Chalmers instead used the report as a springboard to embark on wholesale economic reform.

“This is our blueprint for the future,” Dr Chalmers said.

“Not just understanding the big trends and transitions but acting on them. Turning pressures into prescriptions. Options into opportunities.”

“We can turn these turbulent twenties into the right kind of defining decade. So that in 40 years time, our successors will be able to look back and see that we got it right.”

Australia faces 40 years of budget deficits

The IGR forecasts that GDP growth is set to slow to the slowest pace in more than a century as weaker productivity gains pare back projections for the size of Australia’s economy.

Over the next 40 years, the economy is expected to grow 2.2 per cent a year in real terms – 0.9 per cent lower than the last 40.

At the same time, the budget faces a blowout in the five biggest areas of government spending – the NDIS, aged care, health, defence and interest payments on debt – which will cost $140 billion a year by 2062-63 in today’s dollars.

Currently, the five biggest spending areas cost 8.8 per cent of GDP. By 2062-63, they will 14.4 per cent.

Government spending will skew towards supporting older Australians, with the funding needed to support aged care forecast to more than double in real terms. At the same time, real funding for education and training is expected to fall more than 0.5 per cent.

Despite a projected surge in government spending, the IGR also reveals that the government’s tax take as a proportion of GDP will barely budge, meaning the budget is not expected to return to surplus in the next 40 years.

Changes in consumer behaviour are expected to have a significant impact on the budget. Falling smoking rates and the uptake of electric vehicles will slash the tobacco and fuel excise tax takes respectively.

In the absence of policy change, Australia’s high reliance on personal income taxes will also become more acute, rising to more than 58.4 per cent in the next 40 years, up from 50.5 per cent currently.

The performance of the Future Fund is also expected to worsen in coming decades.

Ageing and changing population

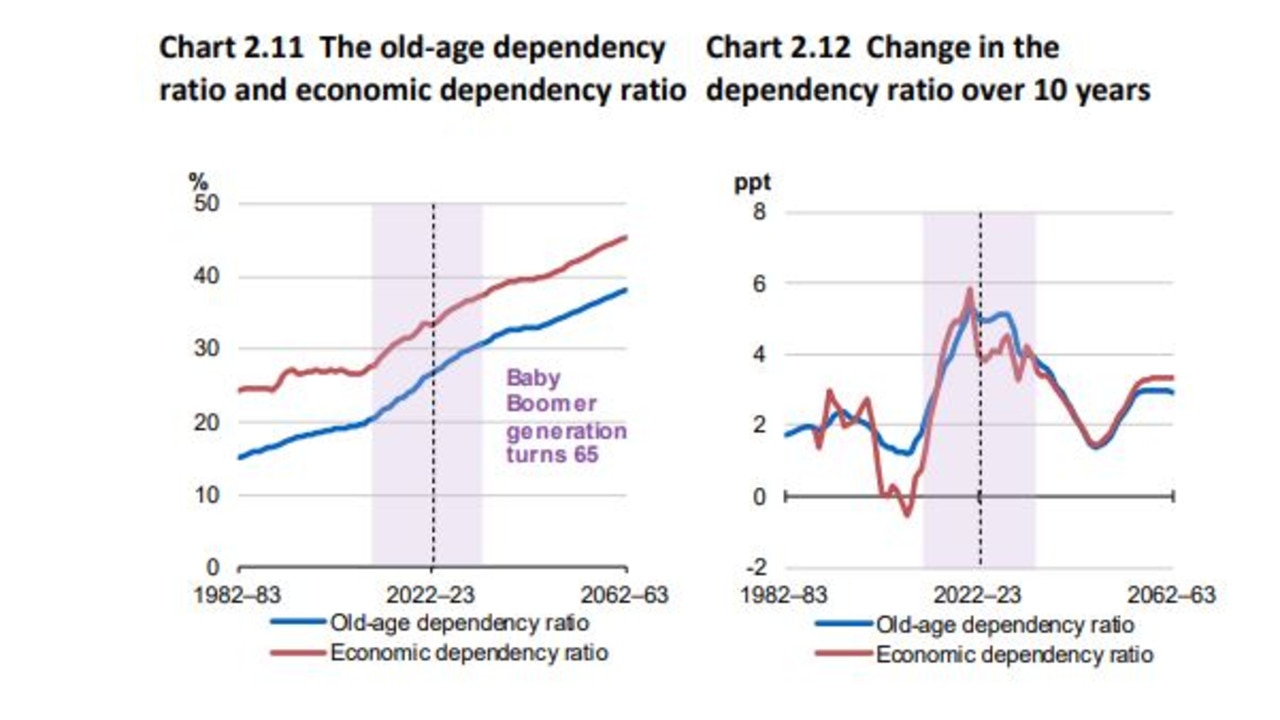

An ageing, slowing population is set to put significant strain on the budget over the next four decades.

Over the next 40 years, life expectancy at birth is projected to increase to 87 years for men (up from 81.3 years today) and 89.5 years for women (up from 85.2 years).

The report warns that “population ageing will affect Australia’s fiscal outlook” because a smaller share of working Australians will mean – without tax reform – lower tax revenues, while at the same time the government’s expenditure on services like health and aged care are set to skyrocket.

“Around 40 per cent of the projected increase in Australians government expenditure from 2022-23 to 2-62-63 is estimated to be due to demographic ageing,” the report says.

The problem will be exacerbated by a projected slow population growth of just 0.8 per cent, and a stagnating fertility rate of 1.62 babies per woman by 2030-31.

While new, young, temporary migrants could help offset the ageing population and be critical to the burgeoning care economy, the report warns that permanent migrants could put further strain

In his speech, Dr Chalmers said there was no hiding from the fact that an older population “will put a strain on our budget”.

“But this will come with a chance to transform our industries in the right way,” he said.

No baby bonus to bolster workforce

The baby bonus era will not be repeated, despite the problems that come with an ageing population and a dwindling workforce.

The report sets out that population growth will slow to 0.8 per cent, and within a decade women will have on average 1.6 babies each.

When asked whether future governments would need to consider reintroducing a baby bonus like the one introduced by Peter Costello 20 years ago, Dr Chalmers said there were other levers available.

“The baby bonus served a purpose in the early 2000s, but … we have found a better way, I believe, to service the same objective, by extending paid parental leave, making early childhood education cheaper, so that parents – particularly mums – can work more and earn more if they want to,” he said.

“And that really goes at the same sort of challenge that Peter Costello was describing … 20 years ago.

“When he sat down and saw the challenges posed by an ageing population, he considered the baby bonus to be the best response to that. When (Finance Minister) Katy (Gallagher) and I look at these similar set of challenges, we think with PPL and early childhood education you get more value for money.”

But the question remains as to how a workforce growing at a slower pace than the ageing population will be able to care for the larger cohort.

Climate impact on the economy

Climate change will be one of the biggest challenges to the economy over the coming 40 decades, but Dr Chalmers says it also offers new opportunities.

The IGR projects that if global temperatures were to increase over four degrees, without adaptive changes, aggregate productivity could decrease to 0.8 per cent by 2063; which would reduce economic output by up to $423 billion in today’s dollars.

The report also warns that inaction on climate change would put significant strain on Australia’s agriculture and tourism sectors over the coming decades.

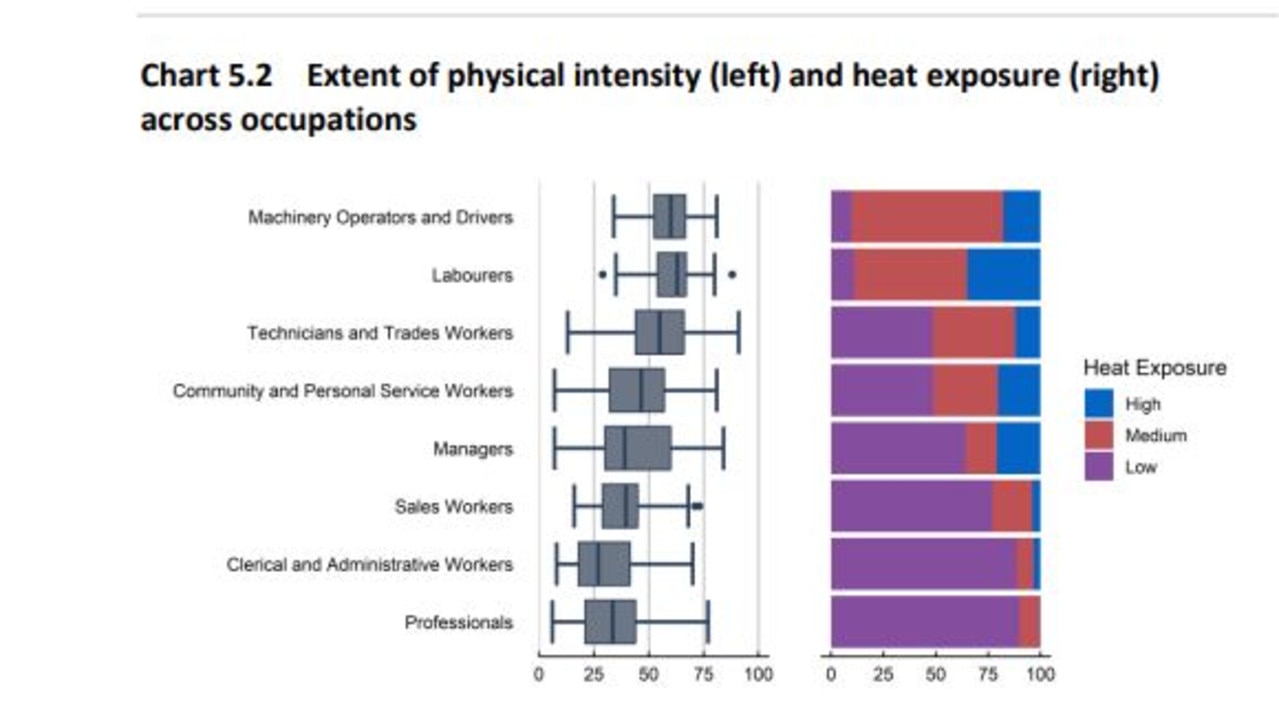

A changing climate will also impact productivity, with rising temperatures set to have a significant impact on the number of hours labourers especially can safely work outside.

The report also warns that the physical effects of climate change will put strain on the budget, calling for “timely investment” in climate change adaptation to build resilience and “reduce the costs” over coming decades.

“Dealing with climate change is a global environmental and economic imperative,” Dr Chalmers said.

“The IGR makes clear the costs that could come with rising temperatures, the impact on specific sectors like agriculture and tourism.”

The report also lays bare the challenge that transitioning to net-zero will have on the structure of Australia’s economy, namely because the government will lose significant revenue from traditionally mining and the fuel excise.

Around $225 billion will need to be spent to decarbonise heavy industries and transition the energy system.

But Dr Chalmers says the transformation to a net-zero economy will “also create growth opportunities”.

“These are not only risks to manage, costs to bear, but vast industrial opportunities,” he said.

Critical minerals are set to become a major Australian export, with forecasts a 350 per cent increase in global demand of lithium, nickel, zinc and bauxite will be needed by 2040 in order to reach net-zero by 2050.

Exports of lithium – a key building block for renewable technologies like electric vehicles and wind turbines – are set to double over the next five years alone, with global demand forecast to increase eight-fold by 2063.

Defence and international relations

As the “window of opportunity to deal with potential threats” narrows amid an accelerating military modernisation in the Indo-Pacific region, restraints on the budget will constrain how Australia responds to “potential threats” in the decades ahead.

Noting that the global strategic environment has “deteriorated sharply” over the last decade, and the challenging strategic outlook facing the Indo-Pacific amid China’s military build up, the report says Australia’s security and prosperity are “under increasing pressure”.

But with budget restraints elsewhere, the report warns that governments will have to make tough choices about how they spend money, and “will need to prioritise which national security measures best meet security needs to effectively respond in these challenging strategic circumstances”.

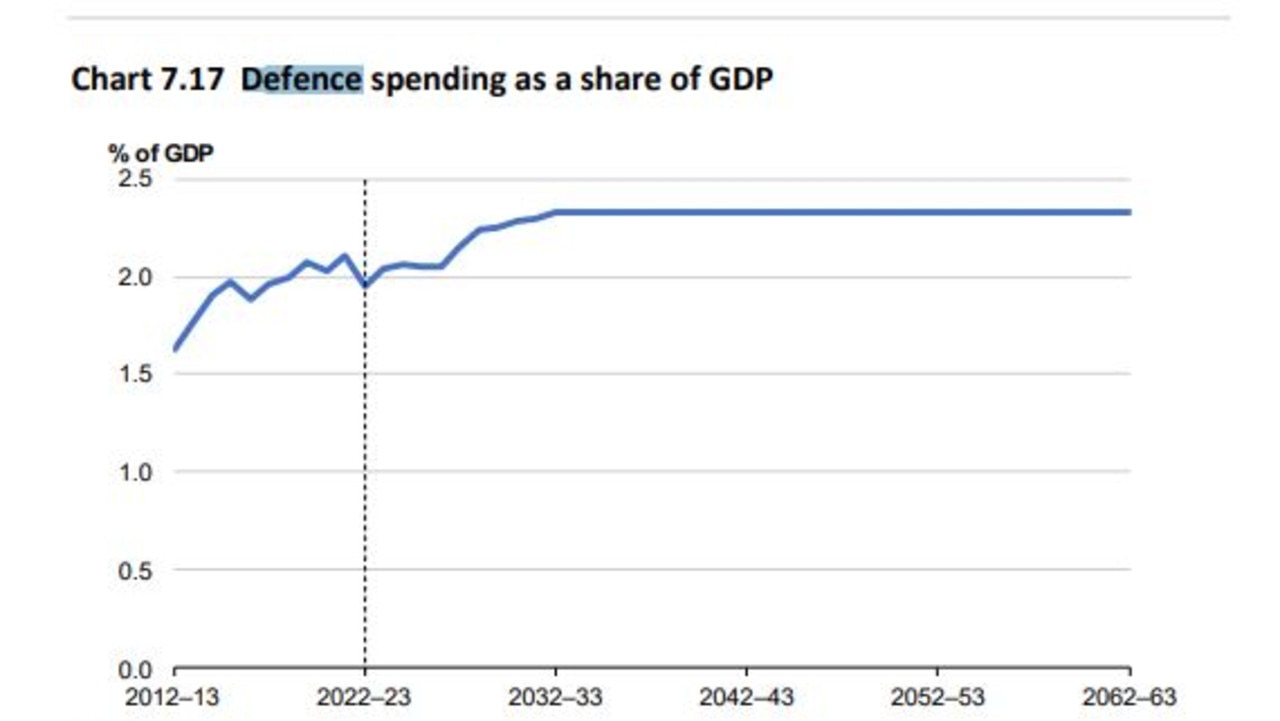

Defence will be one of the fastest growing spending pressures on the budget over the next 40 years. Spending on defence is projected to increase from two per cent of GDP in 2022-23 to around 2.3 per cent in 2032-33 where it will remain put until 2062-63, in line with recommendations of the Defence Strategic Review to “ensure Australia is positioned to respond under these complex strategic circumstances”.

“The government is making major investments in military capabilities and deepening engagement with the region. AUKUS will strengthen national security and Australian industry, supporting exports and jobs in sectors like technology and advanced manufacturing,” the report says.

Expenditure on diplomacy and defence across the region and globally is expected to trend upwards across major economies, while Australia’s national security funding will experience increased pressures in the medium to long term.

The report says governments will need to prioritise funding diplomacy and assistance to best promote regional stability.

It also notes the national security workforce will face increasing challenges due to the limited availability of vetted and skilled personnel.

A productivity challenge

The IGR also shows that Australia’s anaemic productivity growth, which has slumped to a 60-year low over the past decade, is unlikely to substantially improve, thus risking Australia’s quality of life.

Productivity – how efficiently labour can produce goods and services – has become a political flashpoint in recent months, amid warnings that the nation’s weak productivity growth, if not reversed, could lead to a decline in living standards.

“Continuing to improve productivity will be important to realising future economic opportunities and ensuring continued strong growth in living standards,” the report reads.

The IGR also reconfirms the government’s productivity growth assumptions of 1.2 per cent a year.

This follows last year’s October budget, when Dr Chalmers lowered the government’s long-term productivity growth assumptions from its 30-year average of about 1.5 per cent, to its 20-year average of about 1.2 per cent.

In response, the report identifies areas of “opportunity” to enhance Australia’s productivity outlook and underpin the next era of productivity growth.

These include growing the nation’s economic dynamism, encouraging innovation and investment, and skilling Australia’s workforce.