The vote that tore the nation apart

TODAY marks 100 years since this vote that could have “devastated” Australia. If it were held today, would you tick “yes” or “no”?

AS THE struggle over a same-sex marriage referendum becomes increasingly tense, leading historians are pointing back exactly 100 years to a far more divisive public vote, fuelled by racism and class divisions, that tore apart Australia.

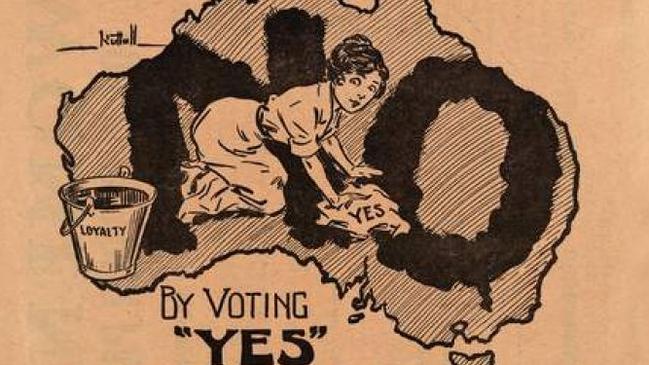

That vote was the First World War plebiscite on conscription, which was defeated by a tiny two per cent margin on October 28, 1916 — and saw bitterness and trolling on an unprecedented scale.

A century on, renowned historian and author Michael McKernan has calculated just how terrible the consequences would have been had it swung the other way — as the then-prime minister assumed it would.

“It was utter madness,” he says. “It would have been devastating for Australia.”

The conscription plebiscite of October 28, 1916, came about after the devastating losses of Australia’s first clashes on the Western Front, at Pozieres and elsewhere on the Somme.

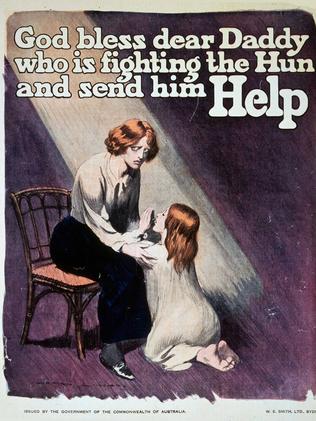

Labor PM Billy Hughes — a man “utterly devoted to the cause of Empire” — believed forcing men to fight overseas was the only way to make up the losses. Volunteers would not be enough. And while he knew his Labor colleagues, who held a majority in the Senate, would block such a move, he felt ordinary Aussies would be behind it — and showing that, with a public vote, would force the senators’ hands.

Hughes was nearly right. The motion was defeated by just 52 per cent to 48 per cent. The narrow margin and the nastiness of the propaganda war, before and after the vote, led to the PM expelling himself from his own party — and forming the Nationalist Party.

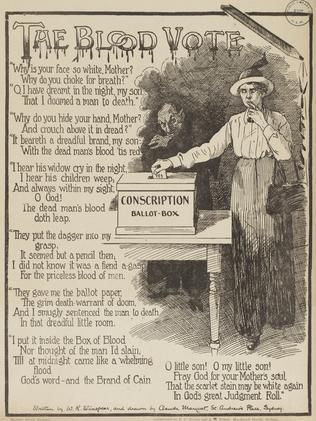

Such were the depths of feeling that vile trolling, as we would call it today, became commonplace. One woman who was publicly in favour of conscription lost her volunteer son in France in early 1917 — and was anonymously sent a copy of an anticonscription leaflet entitled “The Blood Vote”. On the back was written: “from your dead soldier son”.

RACE AND RELIGION

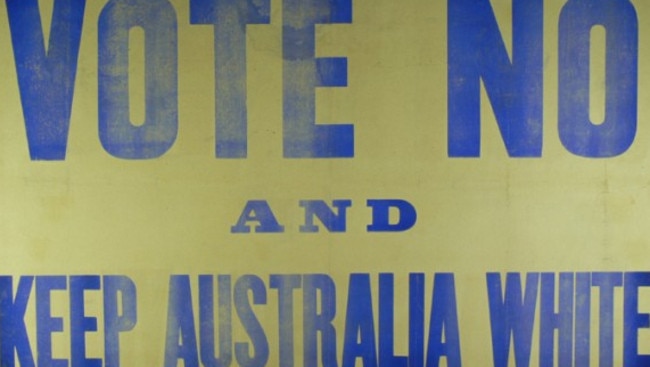

Perhaps surprisingly in 2016, those against conscription in 1916, and a follow-up poll in 1917, relied heavily on racism in their lobbying — protecting the “sacred cow of the White Australia policy” as McKernan said.

Those voting against — largely the working class — feared that conscription would take even more men away from the already decimated national labour force, paving the way for the import of cheap Pacific workers and a resultant drop in pay and conditions.

“Labour was already collapsing in rural areas and in some industries in the cities,” McKernan said. “The men were not being replaced by women as in the UK because that was not seen as seemly.”

Religion also played a part, with a marked Protestant-Catholic divide largely reflecting class positions on the issue. Although senior Catholics were in favour of conscription at first, Melbourne’s Archbishop Daniel Mannix argued against and swayed most of his fellows.

After Hughes lost the vote, he blamed the Catholics — and his views became accepted fact to many, as a December 1916 letter from a mother to her nurse daughter overseas shows.

Mother Davies writes to daughter Evelyn of “terrible things being done by the Roman Catholics, undermining the government.”

The vote was so close. Yet it spared Australia from disaster, McKernan believes.

“If it had gone through, Australia would have suffered almost double the number killed — and let’s not forget thousands more seriously wounded, who would have returned never able to work again,” he says.

“A win for ‘Yes’ would have seen thousands more men taken to the Western Front in time for the battles of 1917, which was the most devastating year of the war for Australia.”

McKernan estimates that under conscription, Australia’s casualty figures would have risen from 60,000 dead and 150,000 wounded to 100,000 dead and 200,000 seriously wounded — this from a total population of less than five million. It would have lead to fewer women marrying, fewer babies and a society and economy in tatters.

“It would have completely changed the whole structure of Australian society for decades to come,” McKernan says, adding that Australia would probably not have fought in the Second World War as a result.

The states were divided in the vote, with Western Australia, Tasmania and Victoria all “Yes” while the others opposed conscription.

And what about those who knew best: the soldiers?

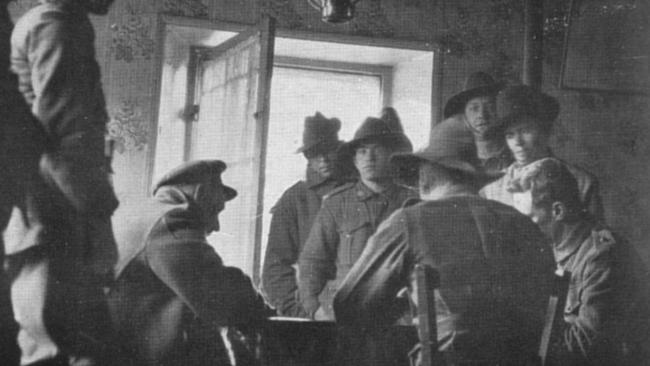

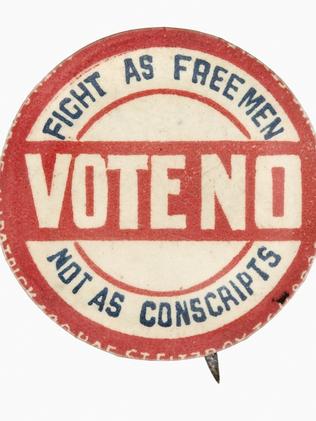

How they voted was not revealed at the time, but McKernan reveals that while recruits in training tended to vote “Yes” those who had already served on the Western Front were mainly “No” — to safeguard their legacy from being tarnished by poor-performing conscripts and because they felt people should only serve in those horrific conditions under their own free will.

AFTERMATH

Meanwhile Hughes was not stopped. As Australia became ever more familiar with the horror of the war (“you could not go anywhere without seeing a woman in mourning black,” says McKernan) recruitment fell and the PM, now leading the Nationalists, called for another referendum.

It was just as bitterly contested, but again the “No” vote won, by 54 per cent to 46 per cent. Conscription would be introduced in the Second World War, and again — highly controversially — during the Vietnam War.

As for today’s same-sex marriage struggle?

“I’m amazed nobody has drawn this link,” says McKernan. “Bill Shorten is walking away because it will be so divisive — and he may be right, if you look at the Irish vote — but it will be nothing like as divisive as the first and second conscription referendums.”

How would you vote if the issue were being debated today? Head to AnzacLive on Facebook and have your say.