‘Record decline’: One ‘dirty secret’ stopping devastating recession from hitting Australia

Australians are suffering through one of the worst economic climates in decades – and things could be about to get a whole lot worse.

ANALYSIS

Earlier this month, Treasurer Jim Chalmers announced that Australia’s first national “wellbeing framework” would soon be released that will comprise around 50 indicators showing how Australians are tracking over time.

Dr Chalmers said the wellbeing framework “will help us track our journey towards a healthier, more sustainable, cohesive, secure and prosperous society that gives every person ample opportunity to build lives of meaning and purpose”.

The Treasurer’s wellbeing framework will arrive at a time when Australians are experiencing a record decline in their living standards.

Real wages – that is, after adjusting for inflation – have collapsed to March 2009 levels.

That’s 14 years of wage gains that have evaporated, with further falls likely as inflation outpaces wage growth.

Australians are also suffering the worst rental crisis in the nation’s history, alongside an energy price shock that has seen electricity and gas bills rise by around 25 per cent down the east coast.

Dirty secret behind Aussie economy

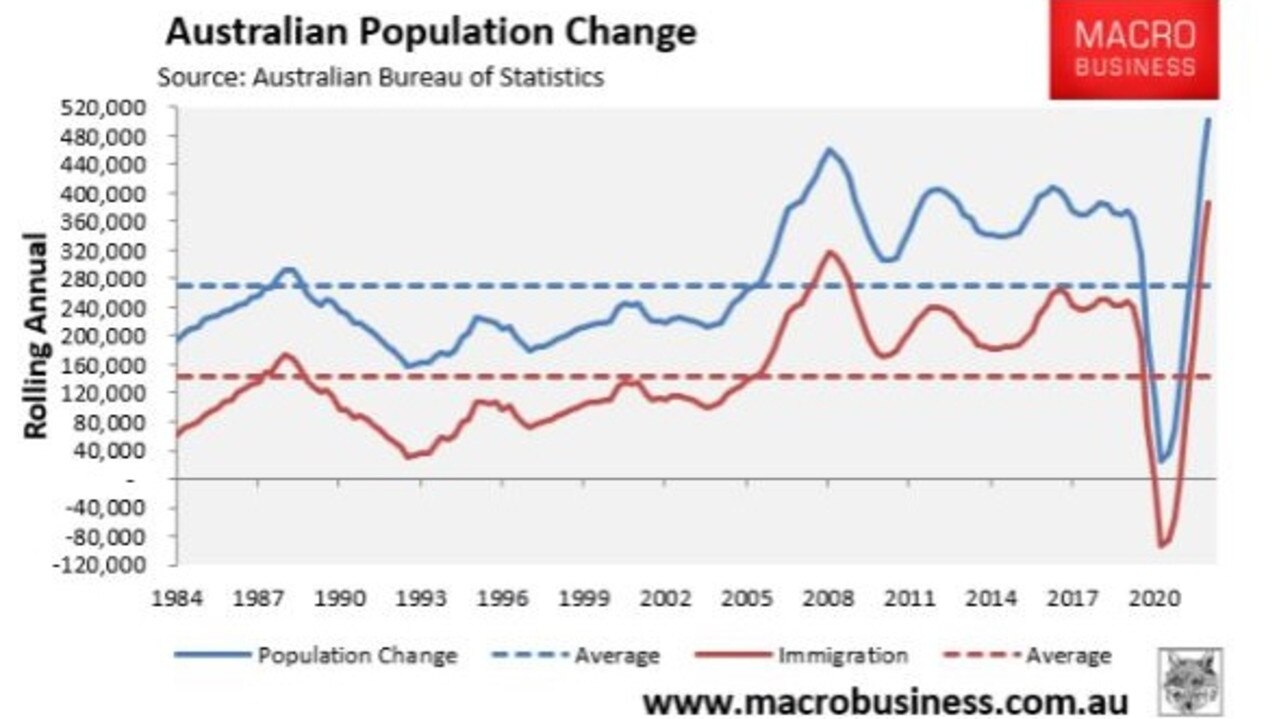

Australia’s population grew by a record 500,400 in the 2022 calendar year, driven by a record net overseas migration (NOM) of 387,000.

The latest federal budget projected that Australia’s population would expand by an unprecedented 2.18 million people over the five-years to 2026-27, equivalent to adding a Perth’s-worth of people.

This projected population expansion would be driven by a record 1.5 million NOM over the same five-year period, equivalent to an Adelaide’s worth of people.

Herein lies the dirty little secret behind the Australian economy.

While other nations have relied on “money printing” – or quantitative easing – to drive their economies’ growth, Australia’s federal government instead relies on “quantitative peopling” – growing the population rapidly via mass immigration to drive our economy.

At the aggregate level, having more people in the economy spending and consuming is positive for economic growth.

Businesses gain from having more consumers to sell to, alongside having a larger pool of workers to choose from: a win-win from their perspective.

But the impact on ordinary Australians’ living standards from high immigration is less positive, since they must compete harder for housing and jobs with new arrivals, while infrastructure, services and the natural environment are crush-loaded by the huge volume of additional people.

Meanwhile, Australia’s economy would slide into recession if not for our record-breaking immigration.

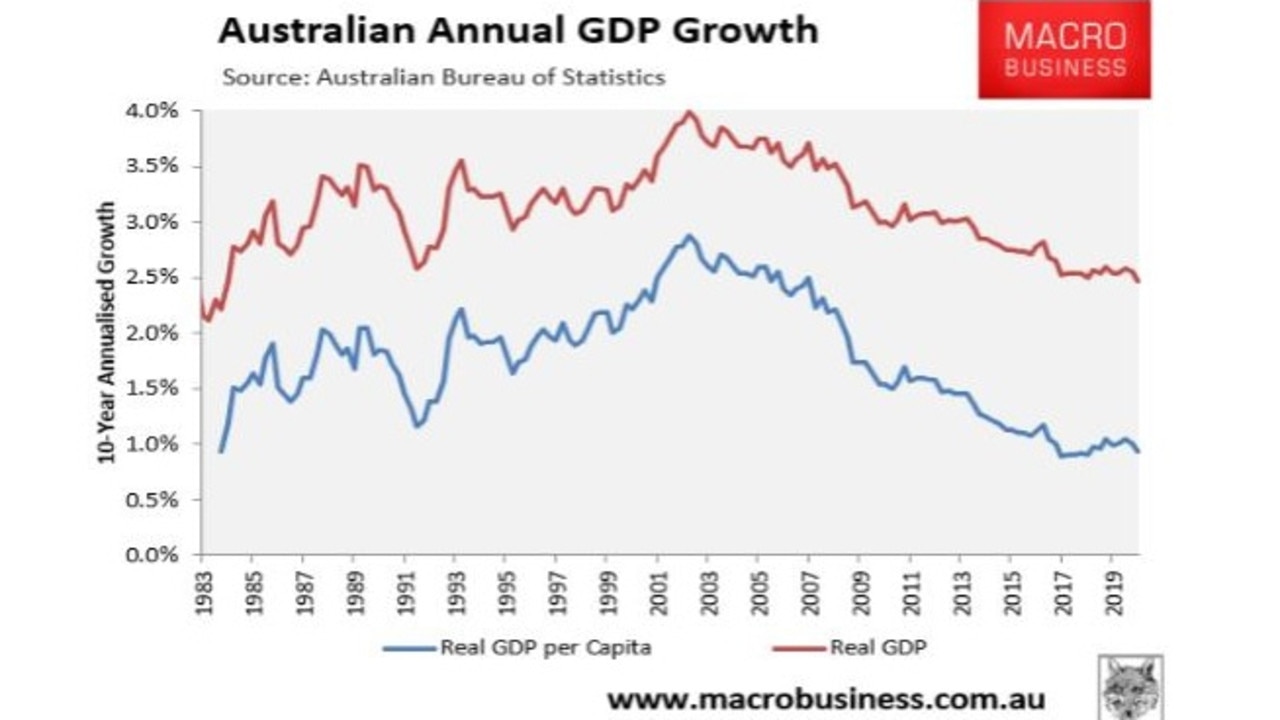

Australia’s gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 0.2 per cent over the March quarter of 2023 against a population increase of 0.4 per cent.

This means GDP per capita fell by 0.2 per cent in the March quarter.

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) projects that Australia’s overall GDP will grow by only 1.2 per cent in the 2023 calendar year, against the federal budget’s projected population increase of 1.9 per cent, meaning per capita GDP will fall by 0.7 per cent this year.

Ratings agency S&P Global is equally pessimistic on the Australian economy. It forecasts slightly stronger overall growth of 1.4 per cent in 2023 and then only 1.2 per cent growth in 2024.

This is against projected population growth of 1.9 per cent in 2023 and by 1.6 per cent in 2024.

Therefore, Australia is facing a two-year recession in per capita terms, according to S&P Global.

Australia’s economic pie will grow via population growth (immigration), but everybody’s share of the pie will shrink.

History never repeats but it sure does rhyme

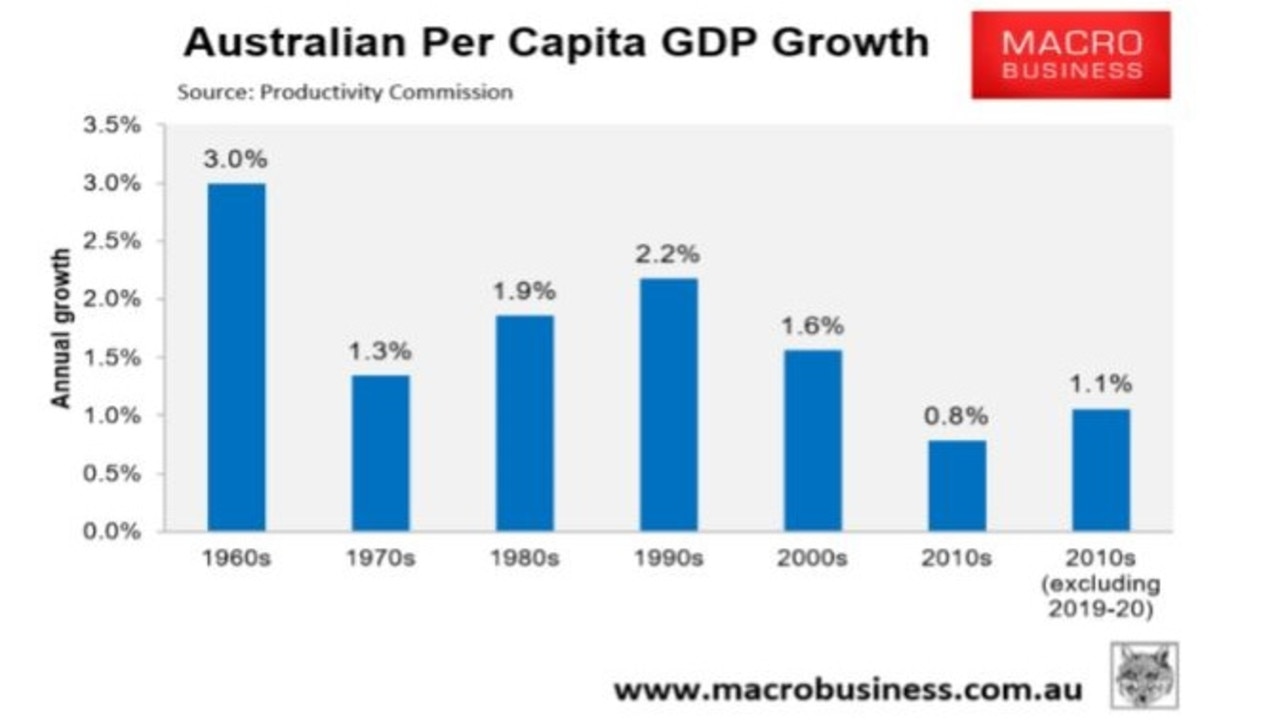

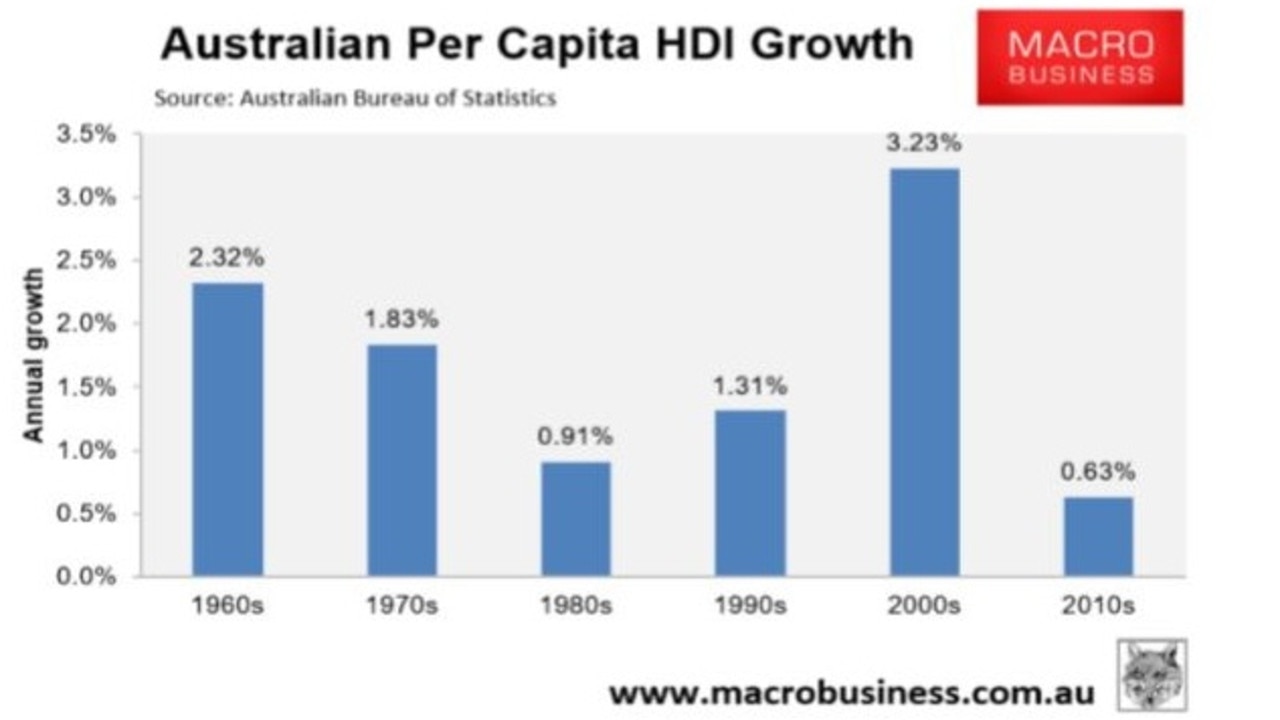

The decade leading up to the pandemic was a lost decade for Australian living standards and provides a harbinger of what lies ahead for the Australian economy, with immigration at fresh record high levels.

Australia’s NOM jumped from an average of 90,500 between 1991 and 2004 to an average of 219,000 between 2005 and 2019 – representing an annual average increase in immigration of 140 per cent.

In fact, between 2000 and 2019, Australia experienced the fastest population gains among large developed nations, with Australia’s population ballooning by 6.6 million people (35 per cent).

Over this period, Australia’s economy became increasingly reliant on population growth, as illustrated clearly in the next chart.

While overall GDP grew at a solid (albeit slowing) rate, per capita GDP growth fell to historically low levels.

In fact, the Productivity Commission ranked the 2010s as the worst decade for per capita GDP growth in 60 years of data, even excluding the impacts of the 2019-20 COVID-19 recession.

It is a similar story for real per capita household disposable incomes (HDI), with the 2010s recording the weakest decade of growth in data dating back to the 1960s.

With the Albanese Government ramping immigration to fresh highs, Australia’s economy will become increasingly reliant on population growth, while individual living standards will continue to decline.

One measure Jim Chalmers should focus on

We do not yet know what indicators Dr Chalmers’ “wellbeing framework” will include.

However, it is safe to assume that it will be designed to paint the government in a positive light and to hide its failures with respect to falling real wages, falling per capita GDP and declining overall living standards.

Any genuine wellbeing framework would show the federal government’s record immigration policy as negative since it directly impacts many facets of life – for example, what sort of home you live in and how much you pay, how long you spend stuck in traffic and whether you can get a seat on a train, whether you can find a place in a hospital or school, or whether you can find space at the park or beach.

Every one of these quality of life indicators is degraded by the federal government’s extreme immigration policy.

Yet I am certain Dr Chalmers’ “wellbeing framework” will be devised in a way that depicts high immigration in a positive way.

Instead of creating a framework of 50 indicators, Treasurer Chalmers should instead focus on one simple measure – per capita GDP – and encourage policy makers, economists and the media to make it their headline statistic (rather than overall GDP, which is the current focus).

Per capita GDP is already produced by the Australian Bureau of Statistics as part of its quarterly national accounts release. It is easily understood. And it provides a simple and effective indicator of whether material living standards are improving.

The sad reality is that Jim Chalmers would never agree to use per capita GDP as the central statistic used by government as it would show the mass immigration policy to be a failure and the economy to be in recession.

It is more politically expedient to instead cover up the decline in living standards by continuing to focus on overall GDP, supplemented by a bunch hand-picked indicators designed to obfuscate and confuse.

With population growth caused by mass immigration currently at 2 per cent, overall GDP must expand at least that much to keep your portion of the economic pie from diminishing.

To have a headline GDP recession, the economy must contract by more than the 2 per cent that the population rises.

That is not an easy task, even with the Reserve Bank working hard on it via its rapid interest rate hikes to curb inflation.

Per capita GDP may not be a perfect measure. But at least it sees through the federal government using “quantitative peopling” mass immigration to mask Australia’s economic decline.

Leith van Onselen is Chief Economist at the MB Fund and MB Super. Leith has previously worked at the Australian Treasury, Victorian Treasury and Goldman Sachs.