‘Ponzi scheme’: Why 2023 Intergenerational Report sets Australia on path to ruin

Australia is hurtling down a dangerous path, with one expert warning we now face a “congested, high-rise future in a degraded environment”.

In 2001, when Australia’s population was 19.3 million, then-Treasurer Peter Costello released the inaugural Intergenerational Report (IGR).

The 2001 IGR forecast that Australia’s population would grow to 25.7 million people by 2050, driven by annual net overseas migration (NOM) of 90,000.

The following year in 2002, a Senate Inquiry put forward by the Howard Government on behalf of the business lobby complained of “serious skill shortages and skill gaps” in Australia and warned that unless the nation did something about it – ie imported a lot of workers – the economy would not develop and would end up going backwards.

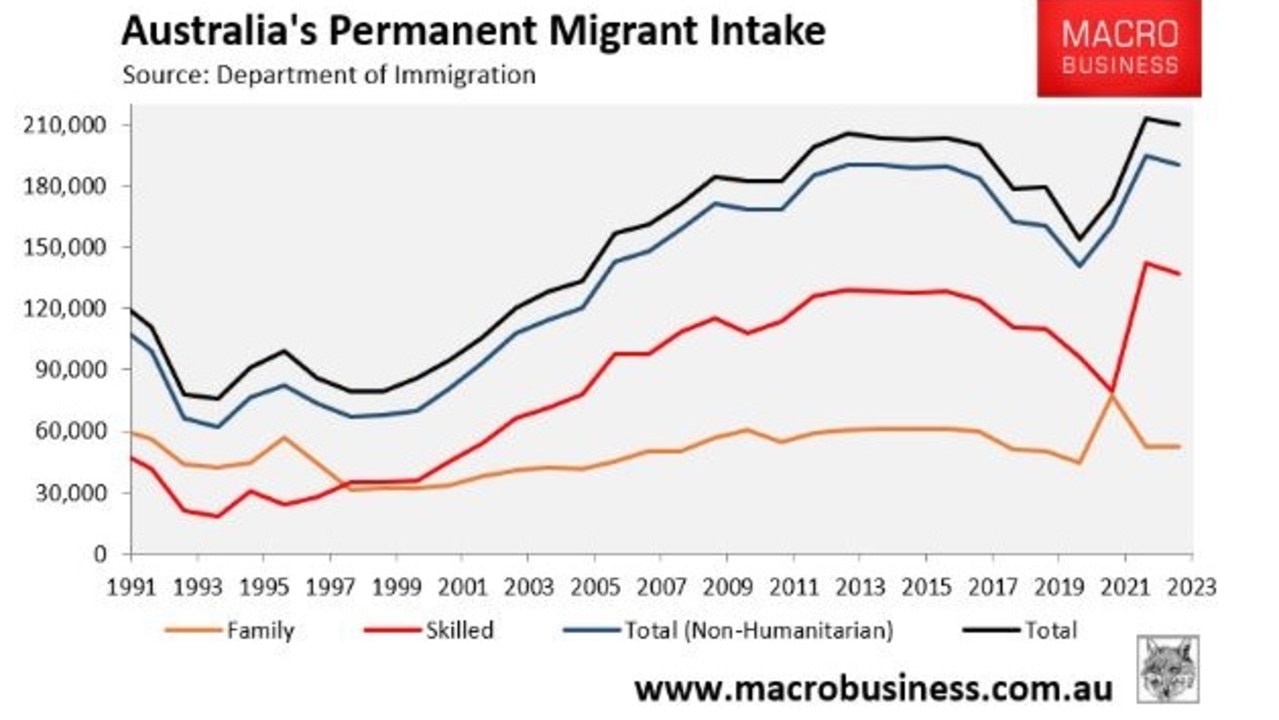

In response, the Howard Government progressively increased the permanent migrant intake from 93,000 to 150,000 in 2007.

Subsequent Labor and Coalition governments then lifted the permanent migrant intake further to its current planning level of 190,000 a year.

The separate humanitarian migrant intake has also been lifted from 12,300 in 2002 to 20,000 this financial year.

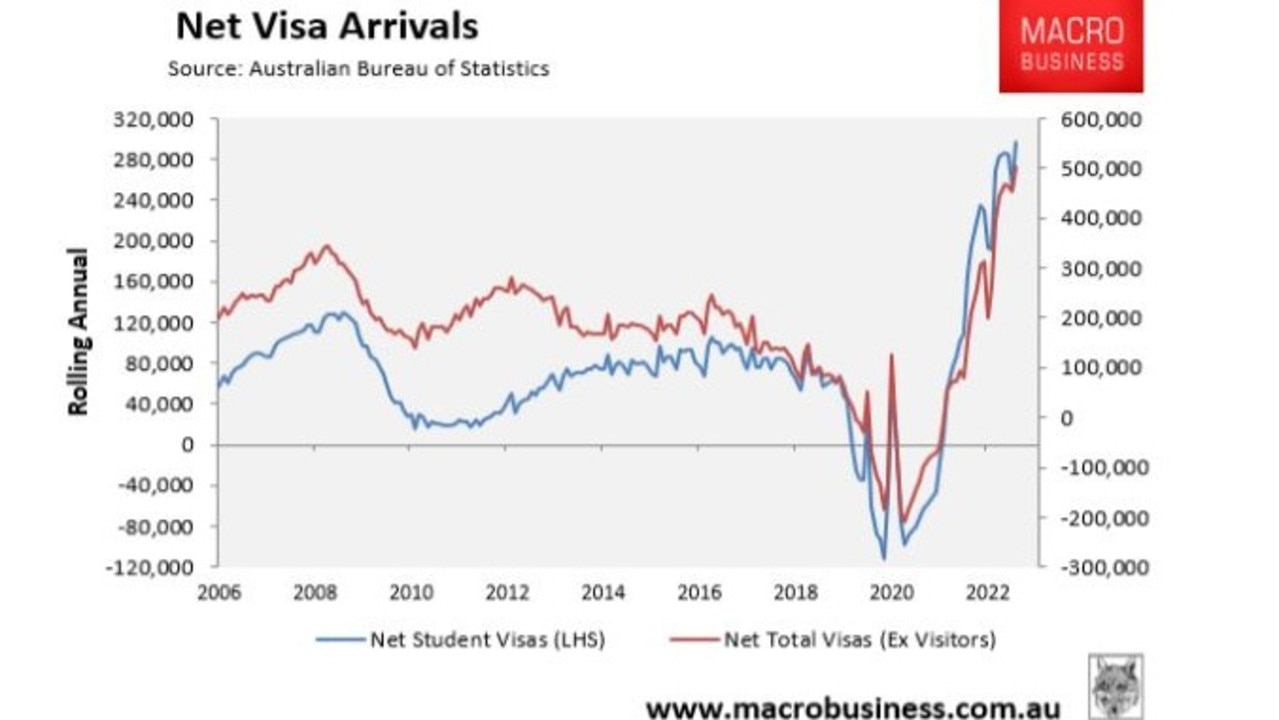

After a strategic review of the student visa program in 2011 (the Knight review), the former Gillard government greatly expanded post-study work rights for international students.

Holders of these graduate (Subclass 485) visas were not required to be qualified for any of the jobs on the Skilled Occupation List. They did not need a firm offer of work from an employer. They were not required to be paid a minimum salary. Nor must they find a job related to their qualifications or require a certain level of skill.

Graduate visa holders could work or study in any job, for any employer. And their visa remains valid even if they cannot find a job.

The Knight review was strongly in favour of expanding post-study work rights because it would greatly increase Australia’s attractiveness as a destination for international students, in turn benefiting Australian universities and employers.

The result was that international education was quickly turned into an immigration industry. Australia’s graduate (485) visas are considered among the most attractive of their kind in the world because they provide full work rights.

They are also highly valued by international students because they are perceived as being a pathway to permanent residency.

International student visas boomed, driving a massive increase in temporary migration alongside the permanent migrant intake.

The Albanese government extended the duration of post-study graduate visas at last year’s Jobs & Skills Summit and recently signed two migration agreements with India that, among other things, will provide Indians with automatic five-year student visas and eight-year post-study work visas.

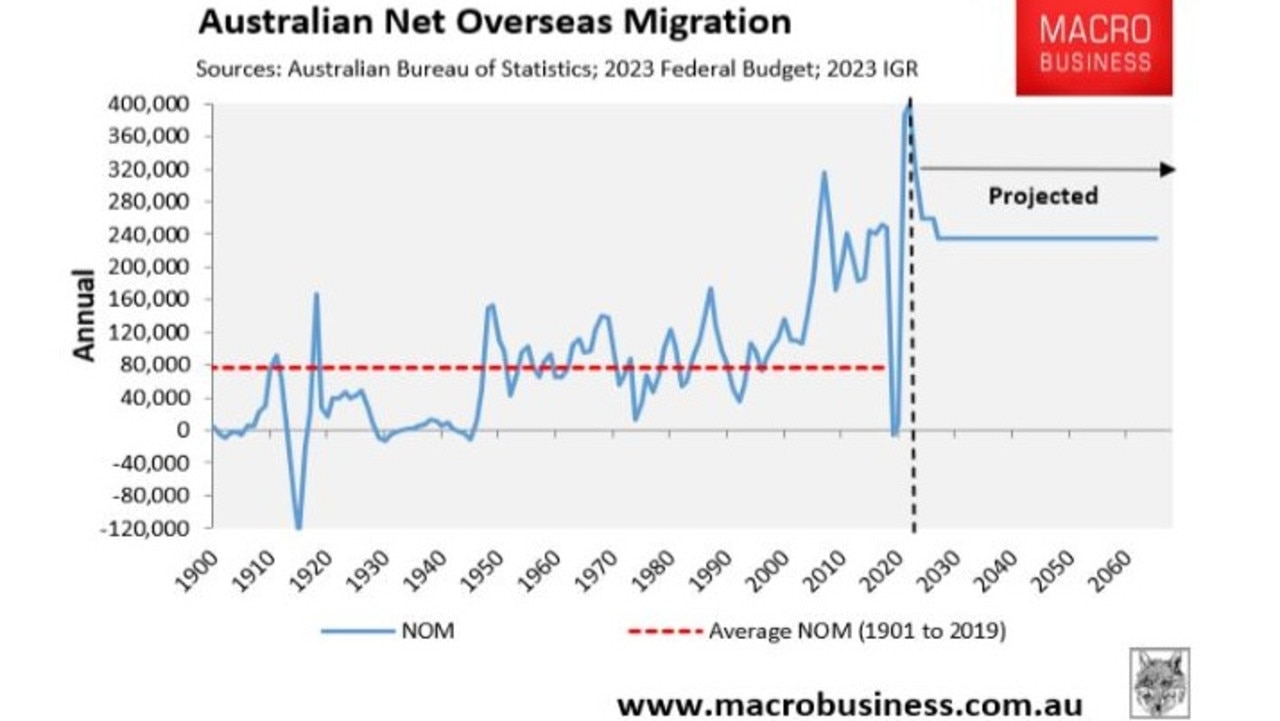

The increase in permanent and temporary migration lifted Australia’s NOM from an average of around 90,000 in the 60 years post World War II to an average of 210,000 since (including the negative years over the pandemic).

As a result, Australia hit the 25.7 million population projection from the 2001 IGR 29 years early in 2021 after growing by an unprecedented 6.4 million people over that 20-year period.

Australia’s major cities also experienced massive growth over this time.

For example, at the 2001 Census, Melbourne had a population of 3.3 million while Sydney had a population of 3.9 million.

At the end of 2022, Melbourne’s population had ballooned by 1.7 million (51 per cent) to 5 million people, whereas Sydney’s population had grown by 1.3 million (34 per cent) to 5.3 million people.

2023 IGR locks in a ‘Big Australia’

The 2023 federal budget projected that Australia’s population would grow by 2.18 million people (equivalent to the population of Perth) over the five years to 2026-27, driven by 1.5 million net overseas migrant arrivals (equivalent to the population of Adelaide).

The 2023 IGR will be released to the public on Thursday.

It projects that Australia’s population will swell to 40.5 million by 2062-63, driven by long-term net overseas migration (NOM) of 235,000 a year.

But Australia hasn’t coped with the 7.4 million population increase this century.

How will it cope with 14.2 million extra residents over the next 40 years, which is equivalent to adding a combined Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Adelaide to Australia’s current population of 26.3 million?

It took Australia 215 years to reach a population of 20 million in 2004.

Yet the 2023 IGR has the nation adding another 20.5 million people in just under 60 years, with Melbourne and Sydney transforming into megacities of around 9 million people.

The path to ruin for Australian living standards

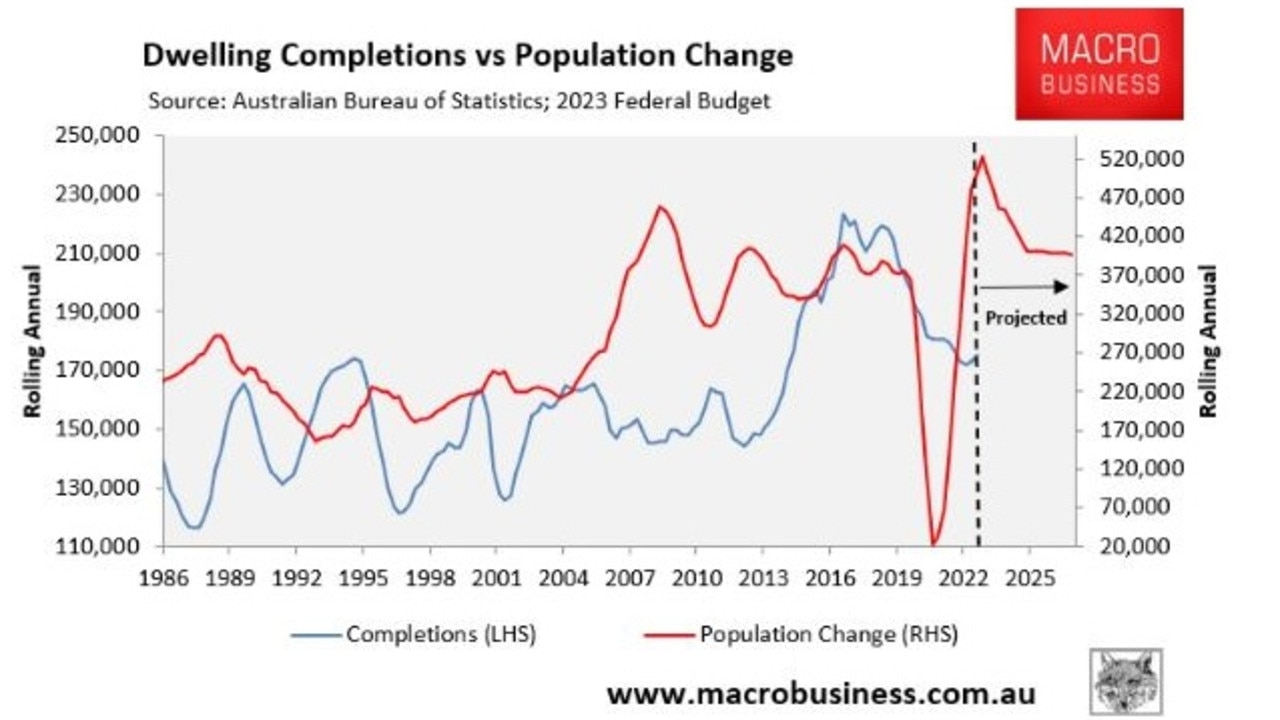

Australians are already suffering from a chronic housing shortage, which has driven rents into the stratosphere and forced thousands of Australians into share housing or homelessness.

This shortage of homes has been driven by decades of high immigration, which has pushed demand above the nation’s capacity to supply new homes.

How will housing supply ever keep pace with demand when Australia’s population is projected to grow by 355,000 people a year on average for 40 years straight via net overseas migration?

Australia didn’t build enough homes over the past 20 years. What makes anybody believe that we will achieve better outcomes over the next 40 years?

Moreover, do Australians want to live in high-rise apartments? Because that will become the norm with a population of 40.5 million.

The same criticisms can be made about Australia’s infrastructure provision.

The 7.4 million population increase this century has crush-loaded everything in sight, including roads, public transport systems, hospitals and schools.

How will Australia catch up on its accumulated infrastructure deficit, let alone provide enough infrastructure for another 14.2 million people?

What about Australia’s water supply? Only four years ago, Australia was grappling with extreme drought and water supplies were running low.

What will happen the next time there is a drought and Australia has millions more mouths to nourish?

To accommodate the extra 14.2 million people, Australia will need to build multiple expensive, energy-guzzling and environmentally destructive water desalination plants. Doing so will also drive up water bills.

This brings us to Australia’s “net zero” climate target.

The Albanese government has committed to lowering Australia’s carbon emissions by 43 per cent in 2030 relative to 2005 as part of a transition to “net zero” emissions by 2050.

How can Australia realistically achieve “net zero” when its population is projected to grow by 14.2 million people, or 54 per cent?

Building construction, operation and maintenance are estimated to account for roughly one-quarter of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions.

The projected 14.2 million increase in Australia’s population would demand the construction of around 5.5 million additional homes as well as considerable new infrastructure.

This construction would lift Australia’s carbon emissions, as would the extra 14.2 million energy users and consumers.

The broader environmental impacts from land clearing to resource use from the larger population would also be devastating.

Economic benefits from high immigration are overblown

At the aggregate level, having more people in the economy spending and consuming is positive for economic growth.

Businesses gain from having more consumers to sell to alongside a larger pool of workers to choose from – a win-win from their perspective.

But the impact on ordinary Australians’ living standards from high immigration is less positive, since they must compete harder for housing and jobs with new arrivals, while infrastructure, services and the natural environment are crush-loaded by the huge volume of additional people.

Population growth also does not increase gross domestic product (GDP) per capita.

The IGR claims that a strong immigration program is necessary to counteract an ageing population.

The line of argument is that migrants typically are younger than the local populace. Therefore, importing people through immigration reduces the population’s average age, resolving the “problem” of the population ageing.

Anyone with a modicum of common sense will see that this reasoning is spurious because migrants also age.

As a result, immigration can at best only serve to postpone population ageing while also bringing with it a host of additional economic and environmental costs associated with having a significantly larger population, as highlighted above.

Importing additional migrants to address population ageing is “can-kick economics”, as today’s migrants will eventually age and contribute to age-related issues in 40 years.

This ageing will then require the importation of even more migrants – the very definition of a Ponzi scheme.

Ultimately, increasing productivity and worker participation are the only ways to lessen the negative economic effects of population ageing.

Both solutions are undermined by high levels immigration, by lowering the ratio of capital-to-labour (termed “capital shallowing”).

AMP chief economist Shane Oliver explained this capital shallowing earlier this month: “Very strong population growth with an inadequate infrastructure and housing supply response has led to urban congestion and poor housing affordability, which contribute to poor productivity growth”.

Finally, the IGR claims that maintaining high levels of immigration is good for the federal budget by increasing the number of workers paying tax.

While high immigration does benefit the federal budget by lifting income tax receipts, it merely pushes the costs onto state budgets (via extra hospital, schools and infrastructure funding) as well as private citizens (via user paid charges like toll roads and higher housing costs).

That’s why we’ve seen state governments privatise everything that’s not bolted down in a desperate attempt to raise money to pay for further infrastructure investment and services, which never keeps pace with population growth.

The best solution to Australia’s budget woes is simply to copy what Norway does and tax Australia’s vast mineral wealth properly.

The Norwegian government received $137 billion from the oil and gas industry last year thanks to its well-designed super profits tax.

As a result, Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund increased to roughly $1.8 trillion, which is shared by only 5.3 million people.

Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund is now worth approximately $340,000 per person, leaving it well-placed to support its ageing population.

Australians wouldn’t need to worry about federal budget debt if policy makers simply taxed our resources properly.

Australia also wouldn’t need to grow the population like a science experiment via mass immigration to plug holes in the federal budget, while pushing the costs onto the states and residents at large.

We need a clever Australia, not a Ponzi-based Australia that uses rapid population growth to mask its decline.

Sadly, the Albanese Government has doubled down on the failed “Big Australia” Ponzi economic model by running the biggest immigration program in history.

In turn, Australians face a congested, high-rise future in a degraded environment.

Leith van Onselen is Chief Economist at the MB Fund and MB Super. Leith has previously worked at the Australian Treasury, Victorian Treasury and Goldman Sachs.