Peter Dutton comeback a shock blow for Anthony Albanese

Peter Dutton seems to be making an unexpected comeback - and it’s bad news for Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, whose days could be numbered.

In the more than a century of Australian political history, the nation’s electorate has overwhelmingly been pretty forgiving of the missteps of federal governments in their first term in office.

In the last 100 years, only one first term government has lost power, the Labor government of James Scullin in 1931.

Others have come close to losing power, most notably the Gillard government at the 2010 election, which ended with Labor and the Coalition having the same number of seats (72) and a minority government.

In recent months, odds have firmed that the Albanese government could join this most exclusive and undesirable club, with aggregate polling sitting at roughly 50-50 and betting odds increasingly favouring the Coalition. Which raises the questions – what has driven such a substantial deterioration of the political fortunes of the Albanese government, and what has historically occurred for a government to lose power after just a single term?

A historical loss

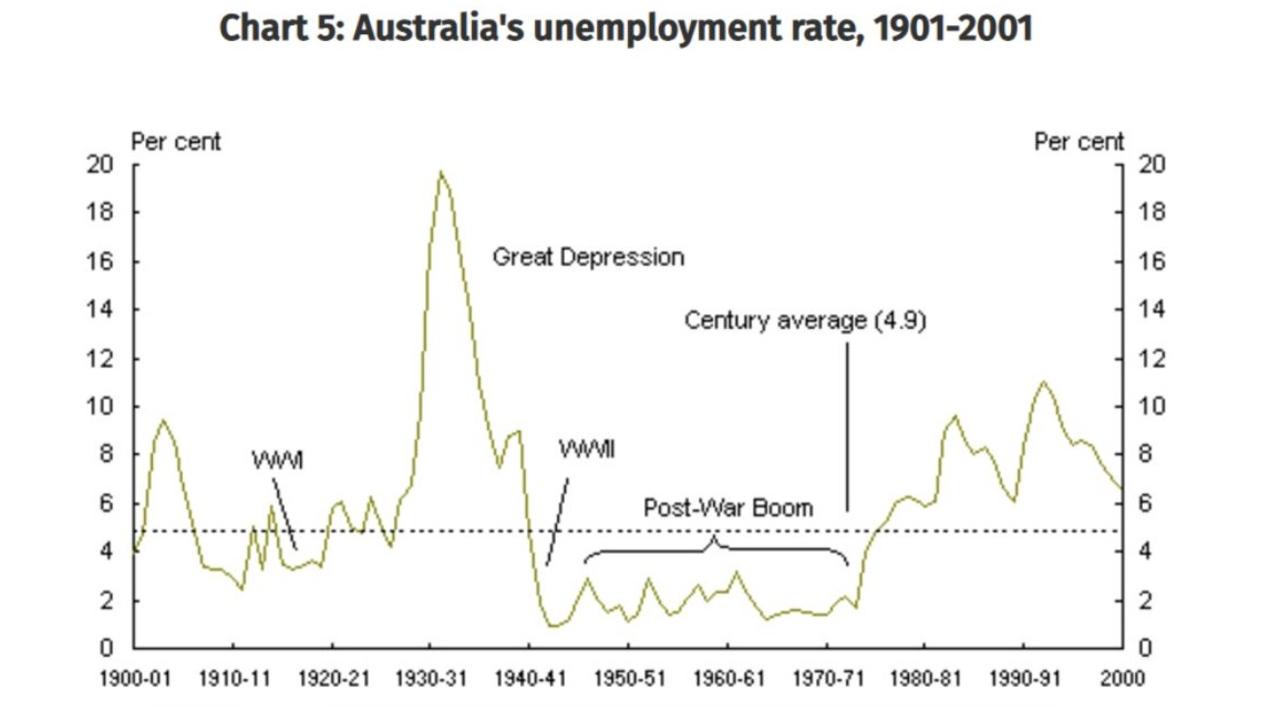

When the Scullin government lost the 1931 election, the deterioration in Labor’s political fortunes did not come as a surprise. The Scullin government was sworn into power just two days before the historic Wall Street stock market crash of 1929, which heralded the onset of the Great Depression.

Amid skyrocketing unemployment that would eventually reach almost 20 per cent and the most challenging economic conditions since the Australian Depression of the 1890s, the Scullin government would see its parliamentary ranks decimated. Despite winning what was the record largest share of lower house seats at the 1929 election, the impact of the Depression and discord over how it should be addressed would see Labor reduced to just 16 seats in a 76 seat parliament, down from 46 seats in the previous election.

Despite presiding over one of the largest defeats in the history of Australian federal politics, Scullin was seen largely as a victim of circumstance by his colleagues and remained the leader of the party until after the next election.

The Economist magazine would later conclude that Scullin “had already done much to place Australia on the high road to recovery (from the Depression)”.

An unwanted path

Despite not facing anything like the challenges experienced by the Scullin government, betting agencies have the Coalition as the current odds-on favourite to win the upcoming election. In order to get a handle on why the Albanese government’s fortunes have deteriorated so significantly – even in the face of an Opposition written off as unappealing not too many moons ago – we’ll be looking at three quantifiable metrics: living standards, inflation and rental vacancy rates.

Living standards

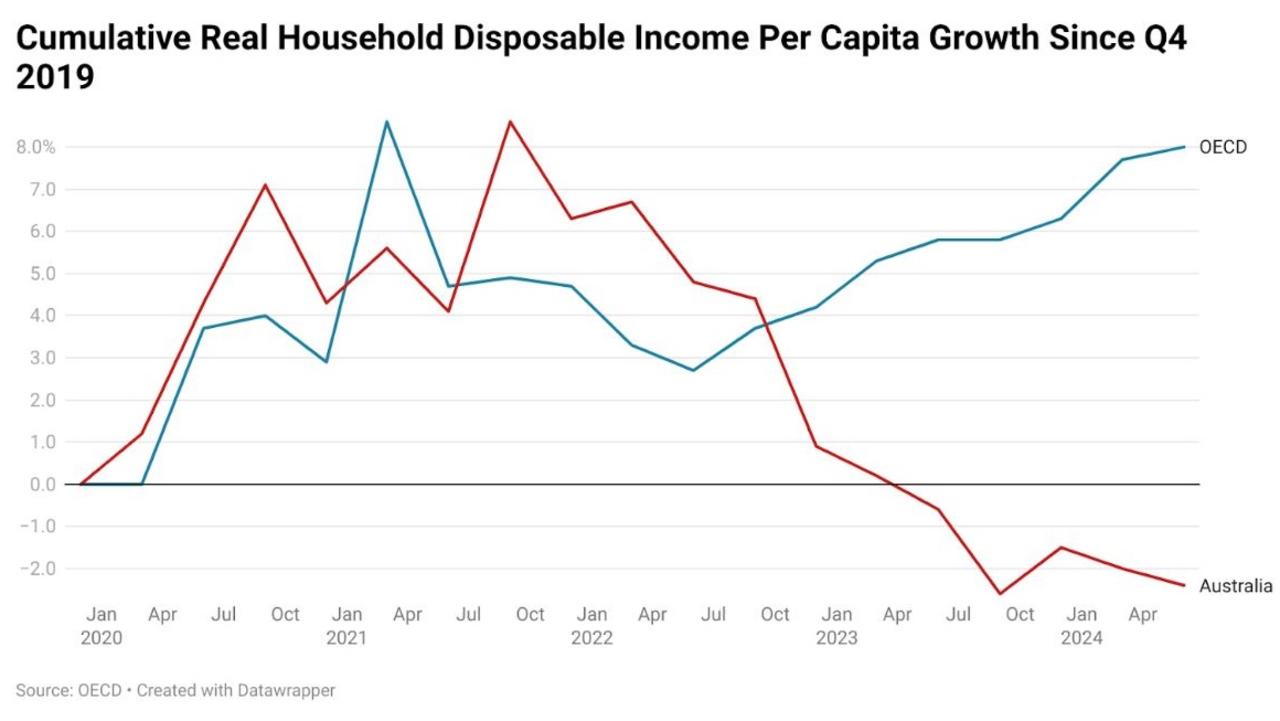

Recently, Australia has made headlines for seeing the largest fall in living standards as measured by real household disposable income per capita of all nations in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Since peaking in Q3 2021, real household disposable income per capita has fallen by 10.4 per cent, the largest fall since records began in 1973. If the growth and peak during the pandemic is ignored, living standards have fallen by 2.4 per cent compared with prior to the pandemic.

Part of the issue for Australia is that while the OECD average got past the Covid induced boost to living standards, bottomed out and then began growing again, Australia’s experience continued to deteriorate before bouncing along the bottom in negative territory.

“The challenge for Australia is that the impact on our living standards has been far greater than anywhere else. There is no argument that the fall (since 2022) is bigger than anything we have seen since 1959,” says independent economist Chris Richardson

Inflation

From London to Wellington, Anglosphere leaders have all faced the impact of inflation on their political fortunes.

Rishi Sunak (Britain), Joe Biden (US) and Chris Hipkins (New Zealand) all lost government over the last 18 months and in each instance, inflation was a factor in their defeat.

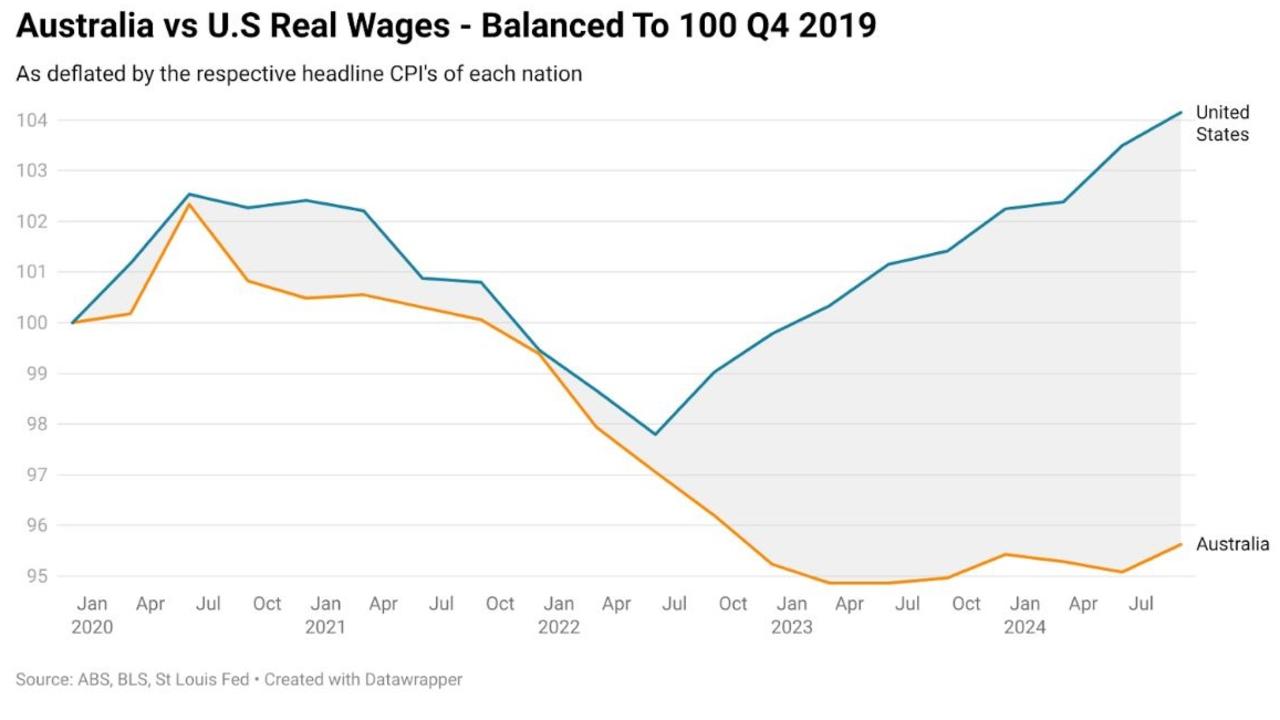

But for Anthony Albanese, things are arguably even more challenging. Today, real wages are roughly where they were at the start of 2010 – and this is what things look like with the temporary but ultimately reversible boost to real wages from various government subsidies reducing headline inflation.

While the real wages growth in some of Australia’s rival major Anglosphere nations has hardly been stellar, the path of Australia’s real wages since the onset of the pandemic has been extremely poor.

Rental vacancy rates

When the Albanese government came to power in May 2022, the nation’s rental crisis was already in full swing. At a national level, the rental vacancy rate was 1.2 per cent, half of what it was in May 2019. As of the latest figures, the nation’s rental vacancy rate is still 1.2 per cent and the rental crisis shows minimal signs of drawing to a close.

Despite rental price growth slowing from the peaks seen in recent years, finding rental accommodation remains a significant challenge in much of the nation.

The reason for the persistent nature of the crisis? Simple supply and demand. Since the Albanese government has come to office, the number of households has expanded by 605,400, while the number of new homes being completed has risen by just 355,200.

While migration as forecast by the federal Treasury continues to slowly decrease, the construction sector remains a long way away from being able to keep up with the ongoing expansion demand, before it can begin to start to make a dent in the nation’s shortage of homes.

The balance

Currently, the latest aggregate polling put together by respected polling analyst Kevin Bonham has the Coalition ahead by the narrowest of margins, 50.3 percentage points to Labor’s 49.7 on a two-party preferred basis.

More Coverage

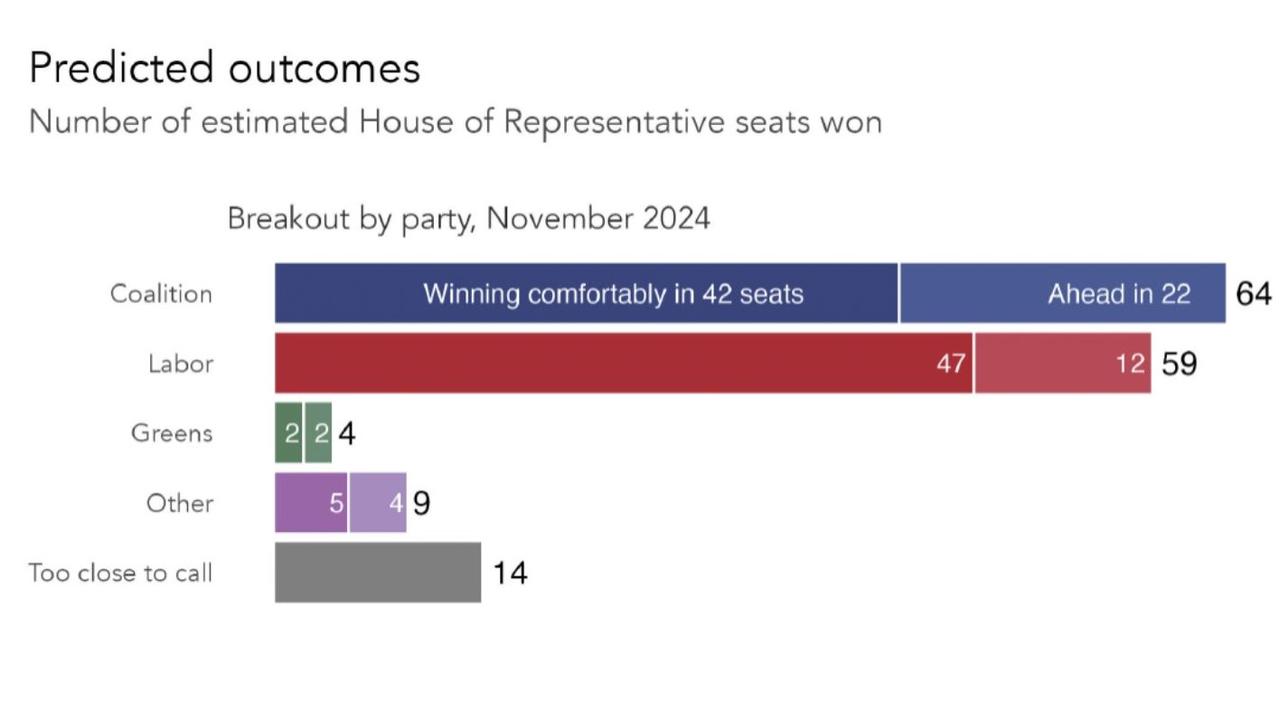

According to polling and subsequent modelling done by Accent Research in conjunction with pollster RedBridge, there is currently a 98 per cent probability of the next election producing a minority government. Their simulation of 1000 elections run using its model and polling inputs concluded that the Coalition would win the largest share of lower house seats in 82 per cent of cases, with Labor winning the most in 18 per cent of instances.

Historically, Australians have been pretty willing to let bygones be bygones for first term governments. Whitlam faced the oil crisis and a contracting economy, Hawke became PM in the middle of a recession with sky high unemployment and Menzies had to cope with the inflationary impact of the Korean War and the subsequent recession – yet all were re-elected. Whether the luck of first term prime ministers will hold out for Anthony Albanese is ultimately in the hands of the electorate.

Tarric Brooker is a freelance journalist and social commentator | @AvidCommentator