Inside Victoria’s controversial Belt and Road Initiative deal with China

It was a secret arrangement that took foreign affairs officials by surprise, and now Victoria’s cosy arrangement with Beijing is back in the spotlight.

On a seemingly ordinary October morning in 2018, senior officials from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade were blindsided in a pretty spectacular way.

A newspaper article about a historic deal between Victoria and China saw a flurry of confused panic ripple through the government’s frontline force for all things global affairs.

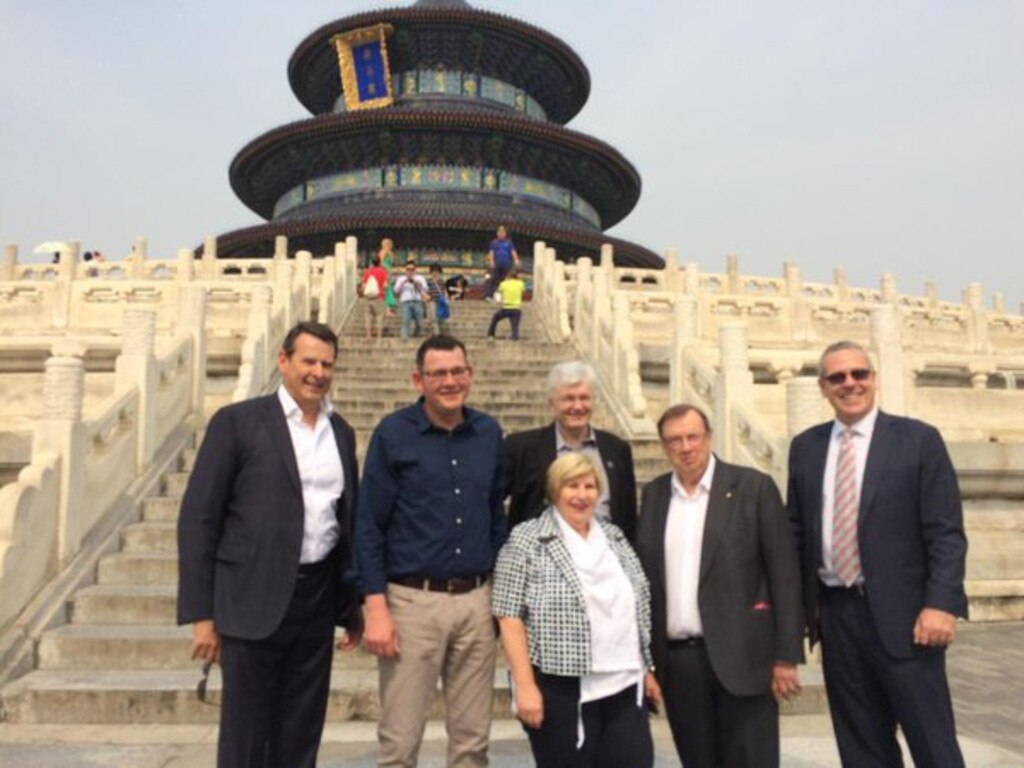

Premier Daniel Andrews had signed a memorandum of understanding with Beijing to make his state a member of the Communist Party’s $1.5 trillion Belt and Road Initiative – the only government in the country to do so.

In fact, it came after the Commonwealth had declined an invitation to sign on, largely out of concerns about China’s true intentions, so the news was viewed as quite astounding to DFAT.

A key player in “Team Australia” had gone rogue and they’d just found out about it at the same time as everybody else.

And now, two and a half years on, the Belt and Roads Initiative is back in the spotlight after Foreign Affairs Minister Marise Payne tore up the agreement on Wednesday night in a move that had angered China and further soured already strained relations between the two nations.

“I consider these four arrangements to be inconsistent with Australia’s foreign policy or adverse to our foreign relations in line with the relevant test in Australia’s Foreign Relations (State and Territory Arrangements) Act 2020,’’ Foreign Minister Marise Payne said this week in a statement.

“I will continue to consider foreign arrangements notified under the Scheme. I expect the overwhelming majority of them to remain unaffected. I look forward to ongoing collaboration with states, territories, universities and local governments in implementing the Foreign Arrangements Scheme.”

The move immediately angered China, with a Chinese Embassy spokesman warning in a statement it could further derail already strained relations between the two nations.

“We express our strong displeasure and resolute opposition to the Australian Foreign Minister’s announcement on April 21 to cancel the Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation within the Framework of the Belt and Road Initiative and the related Framework Agreement between the Chinese side and Government of Victoria,” the spokesman said.

“This is another unreasonable and provocative move taken by the Australian side against China.“It further shows that the Australian government has no sincerity in improving China-Australia relations.“It is bound to bring further damage to bilateral relations, and will only end up hurting itself.”

China's mouthpiece The Global Times also published a scathing op-ed, branding the decision a "suicide attack" which could have potentially "crippling" consequences for Australia.

WHAT IS THE BRI?

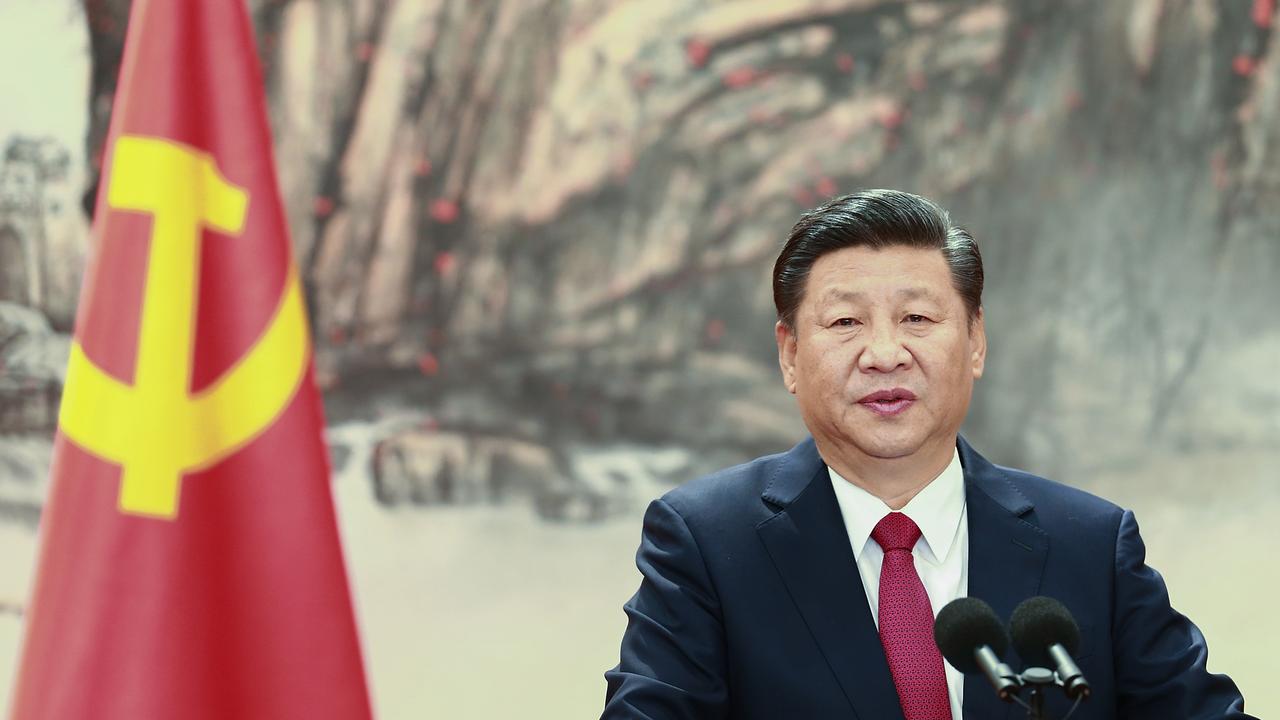

Chinese President Xi Jinping announced the ambitious One Belt, One Road project – more commonly referred to as the Belt and Road Initiative – in 2013, calling it “a bid to enhance regional connectivity and embrace a brighter future”.

In summary, it’s $US1 trillion ($A1.44 trillion) of spending in 138 different countries to create a global trade route. “Belt” describes overland routes for road and rail transportation, while “road” describes maritime passages.

Mr Xi set the lofty goal of completing all of the BRI projects by 2049, coinciding with the 100th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China.

RELATED: Victoria’s Belt and Road deal with China raises concerns

RELATED: Australia to introduce new rules on foreign takeovers that inflame relations with China

“There is a diverse array of projects encompassed under the BRI umbrella, focused on six main ‘economic corridors’,” Associate Professor Michael Clarke from the National Security College at the Australian National University explained.

“These corridors link China to Central Asia, the Middle East and Europe by land, and to Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, the Pacific and East Africa by sea (the ‘Maritime Silk Road’).

“To date, China has pledged an estimated $US1 trillion in investments in ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ infrastructure, from ports and high-speed rail to telecommunications and cyberspace, and signed memorandums of understanding with 138 countries.”

The flowery language describing Beijing’s goals weren’t enough to stop concern being felt by many nations in the years after it was announced.

From a purely economic perspective, Associate Professor Clarke said those concerns are valid.

“Many BRI projects are financed through Chinese public financial institutions such as the Export-Import Bank of China that enjoy low borrowing costs and interest rates,” he said.

“This enables them to lend on favourable terms to Chinese companies, who can then significantly undercut foreign companies for infrastructure bids.”

Another concern raised on many occasions relates to accusations that China was engaging in “debt trap diplomacy”, he said.

Essentially, the view is that Beijing extends massive loans to countries that will struggle to ever pay it back, and then leans on them to extract political and economic concessions.

In some regions, such as the Pacific, that level of influence could represent a national security risk for the Western world.

RELATED: Chinese businesswoman Jean Dong was a key figure in Victoria’s controversial trade deal with CCP

VICTORIA’S CURIOUS DEAL

A chunk of the blame for the level of public distrust about the arrangement lies with Mr Andrews and his government for the secretive nature of the deal.

For one, the first the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade knew about Victoria’s deal with Beijing was when media reports about it emerged.

“It was extraordinary at the time,” Dr Graeme Smith from the School of Asia Pacific Affairs at ANU said.

No one at a federal level seemed to know it was coming – something that’s fairly unusual in normal dealings.

The “Canberra gossip” at the time was that DFAT and the Department of Defence had been cut out of consultation entirely, Dr Smith said.

“They had no idea it was going ahead until the announcement was made, which was unusual.”

The Commonwealth seemingly wanted nothing to do with BRI itself, despite the potential to pump billions of dollars into the country’s northern regions, Professor Peter Lloyd from the University of Melbourne said.

“It did this in part because of concerns about China’s strategic intentions,” Prof Lloyd, an economist, wrote for The Conversation.

And then on top of all that, Mr Andrews initially refused on multiple occasions to release the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) document, only relenting after growing pressure on the eve of an election.

The Victorian Government established a working group after signing the MOU, to develop a framework to guide the partnership.

“With the biggest infrastructure program in our state’s history under way, we have the design and delivery skills China is looking for, meaning more jobs and more trade and investment for Victorians,” Mr Andrews said in October 2018.

While it was initially designed to promote investment in Victoria’s mammoth pipeline of infrastructure projects and boost exports from the state, it evolved in the months since.

The developed framework eventually revealed the now torn up BRI partnership was set to go beyond infrastructure investment to include technology and agriculture investment.

But for all of the controversy then and now, there’s an important point in all of this, Dr Smith said.

“The deal obliges Victoria to do absolutely nothing, so it’s not as though they’ve signed away Australia’s sovereignty.”

IS THERE ANY BENEFIT?

At the time, Mr Andrews promised the BRI would deliver jobs, investment and economic growth - but Professor John Fitzgerald, a China expert at Swinburne University of Technology, was always sceptical about any real benefit from the deal.

“The BRI does not appear to be helping with jobs, trade, or investment,” Prof Fitzgerald wrote in an article for The Mandarin.

Further, he said that by signing up, “Andrews has arguably placed his state in peril”.

“Although the BRI deal has brought little or no benefit to Victoria, the fact remains that once a government signs on to an agreement with Beijing, the consequences of reversing the agreement can be far worse than not signing on in the first place,” Prof Fitzgerald wrote.

“In this sense, the premier has hung an albatross around the neck of his own and any future government of Victoria.”

RELATED: China pro-government newspaper publishes article labelling Australian MPs ‘thugs’

Victoria should instead invest more effort in broadening trade and investment agreements with countries like India, Japan and Vietnam, Prof Fitzgerald said.

“In weighing up the costs and benefits of the immense effort Victoria has expended in building trade and investment links with China, for no appreciable value added, we have to consider the opportunity costs of not investing comparable effort in relations with Japan and India and other countries in the region.”

Michael Shoebridge is the director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s Defence, Strategy and National Security program, and he’s equally confused about why the BRI deal still exists.

“If it’s about cheap financing, the COVID-19 environment means money is as cheap for governments to borrow as it has ever been, so that reason doesn’t make much sense,” Mr Shoebridge said.

“If it’s about giving Chinese firms work, there are plenty of Australian companies that are at least as qualified and available to undertake infrastructure projects.

“If it’s about using Chinese digital technology in our infrastructure, that’s probably just a bad idea.”

Dr Smith said the benefits of Victoria’s BRI deal are “clearer on the Chinese side”.

“On the Victorian side, it does buy them good will, relative to other state governments, with China at a time when relations between it and most other nations aren’t great,” he said.

But that’s about it.

“Thus far, I think it’s been a bit of a disappointment for the Andrews Government, in the sense that the big investment in infrastructure projects haven’t materialised,” Dr Smith said.

From Beijing’s perspective, it gets to include Australia as a BRI member state – even though it’s just Victoria – so “propaganda-wise, it’s great for them”, he said.

In the current global political and economic climate, Victoria’s relationship with China makes even less sense, Mr Shoebridge said.

“And the Victorian political leadership’s championing of the state’s tie-up with Beijing on infrastructure is a glaring wedge that Beijing is driving into Australia – at a time when national cohesion on dealing with the Chinese state is essential.”

WHAT’S CHINA’S GOAL?

As tensions between Canberra and Beijing escalated, sparked by the government’s lobbying for an inquiry into COVID-19, leading to trade barriers from China, Victoria’s Treasurer Tim Pallas chose to use some intriguing language.

Mr Pallas blamed the government and Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s “inelegant interventions” for the hefty tariffs on barley producers and a ban on some beef abattoirs in Queensland.

And while he conceded an inquiry into the pandemic was necessary, Mr Pallas slammed the “vilification” of China and warned that it was “dangerous, damaging and probably irresponsible in many respects”.

Mr Shoebridge said the optics of the extraordinary intervention by a state politician about national foreign policy and trade was damaging.

It gave the appearance that Australian governments were at odds over China.

“Unfortunately, the Treasurer’s words sounded like talking points from Beijing’s foreign ministry or an article in the Chinese Communist Party’s Global Times mouthpiece,” he said.

The Victorian Government coming to Beijing’s defence so enthusiastically would’ve played well in China, Dr Smith said.

“And that’s absolutely part of China’s MO when it comes to foreign policy, to promote the impression of division in the West – and even to sow division,” he added.

Dr Smith said the comments were “very off” in the context of the COVID-19 crisis, but also continual revelations about human rights abuses in prison camps in Xinjiang, and in light of attempts to cripple freedoms in Hong Kong.

“That kind of language would’ve probably been fine three years ago, but now it seems very off. It’s like, seriously?”

There’s no doubt that China’s BRI goal has a big “geo-strategic element to it”, he said.

“You can see it in the birth of the Belt and Road Initiative. It was a defensive response to the Obama Administration’s pivot to Asia. Beijing needed to strengthen trade links and strategic links.

“It’s an investment project to encourage trade. But, there’s an element of companies who are part of BRI being expected to do the State’s bidding.

“The language structuring the initiative is very broad, it’s very ambiguous, and so it’s hard as an outsider to determine what the State can make these companies do.”

VICTORIA’S BRI DEAL SLAMMED

Political pressure soon began mounting on Mr Andrews to abandon Victoria’s deal with China, with Mr Shoebridge issuing a blunt assessment, saying: “It needs to be halted and reassessed.”

Opposition Leader Michael O’Brien also said last year that China’s trade retaliation, which had impacted some Victorian farmers, revealed the BRI was a “dud”.

“This is not about trade, this is not about jobs. This is all about political influence,” Mr O’Brien told reporters.

“They’re looking to grow Victoria’s exports and grow investment, and that doesn’t play badly with Victorians. You have to remember, it’s essentially a city state – it’s Melbourne with a little bit of regional influence.

“You have a very urbanised population who are aware of the state’s connection to the global economy in a way that other parts of Australia aren’t quite as much.

“However much on the nose China might be, there’s an awareness of the importance of the relationship.”