How the baby bust sparked Australia’s international student explosion

Australia’s international student explosion has transformed the education sector into a $51 billion export. Here’s why it’s become such a divisive problem.

Depending on who you ask, they’re at once the engine room of the Australian economy and the driving force behind the country’s population squeeze.

But for the man who started the ball rolling on Australia’s international student explosion two decades ago, there was only one number on his mind.

Dr Abul Rizvi, former deputy secretary of the Immigration Department, was one of the key architects of the Howard-era immigration boom.

And former Prime Minister John Howard and then-Treasurer Peter Costello weren’t thinking of dollars or houses — it was babies keeping them up at night.

“I think the key was the question of ageing, and what happens when fertility rates start to drop to very low levels,” Dr Rizvi said.

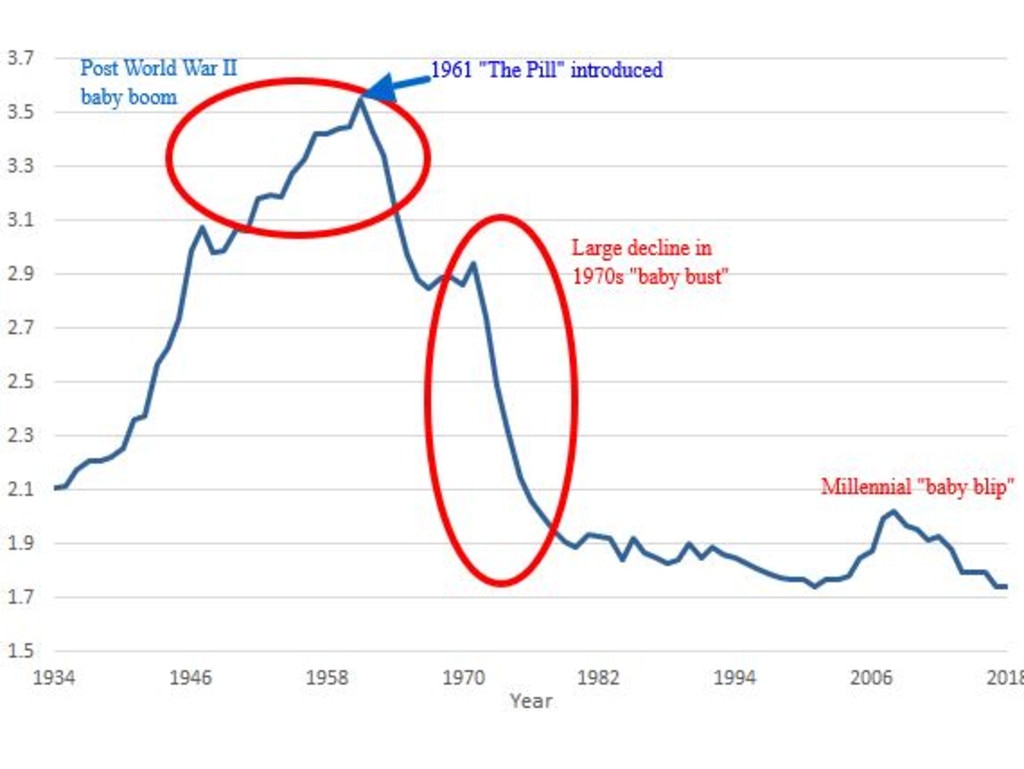

“We had always hoped that our fertility rate would never drop below 1.5. It’s now around 1.5, so it’s about as low as we hoped it would ever go.”

Australia’s birthrate hit the new record low in 2023. The number of babies born per woman has been sharply declining since the 1960s, following the advent of the contraceptive pill and increasing female workforce participation.

In 1976, the birthrate officially fell below replacement level of 2.1, and has never recovered.

“A fertility rate of 1.5 really means in the long-term, without immigration, your population firstly ages faster, and it’s the rate of ageing that’s key here,” Dr Rizvi said.

“Most economies are not used to very rapid rates of ageing. Most economies have grown up with more people in working age than more and more people in the 65-plus age.

“So it was the rate of ageing that we wanted to slow, we wanted to push back the day that deaths exceeded births. We were looking across at Japan and their demographics and thinking, ‘Geez, we don’t want to be there’.”

Japan, with a birthrate of just 1.2, has long been considered a demographic warning to the developed world.

Births in 2024 fell for the ninth consecutive year to a new record low of 720,988, while deaths also hit a record of 1.62 million — meaning more than two people died for every baby born in Japan last year.

At the turn of the century Australia’s birthrate was still hovering around 1.8 — and even briefly spiked back above two in 2008 — but the long-term trend was causing consternation among bureaucrats.

“We were talking to the Productivity Commission, Treasury, Finance and ministers,” Dr Rizvi said.

“Costello talked about his baby bonus but frankly that did not do a lot. He took credit for fertility rates briefly increasing, but fertility rates naturally have a cycle based on the age of women in the cohort. People talk about the baby boom, then the baby echo, then there’s the baby echo echo, but over time it declines.”

You can lead a horse to water, as the saying goes, but you can’t make it drink.

‘Let it rip’

For politicians and number crunchers, there was only one solution — rapidly ramping up immigration. And universities would be the key to supplying “Big Australia” with a young, educated workforce as the mining boom kicked off.

“The universities were certainly pushing for a new revenue stream, no question, but if it were not for the demography issue the policy in respect of students would not have come around,” Dr Rizvi said.

The Australian Population Research Institute (TAPRI) founder Bob Birrell has been researching Australian attitudes to immigration since the 1980s, since the days of the Hawke Labor government’s National Population Council.

“The really big change occurred in the early 2000s when the Coalition government changed the rules on overseas students, initially allowing them to stay on in Australia after completing their courses,” Mr Birrell said.

“But then during the 2000s they opened up opportunities for students who’d completed vocational or university courses to apply for permanent residency onshore,” he said.

“That generated a massive spike in the number of overseas students here, particularly in the vocational area. We had nominally some 300,000 at the end of the 2000s as a consequence.”

Almost since the beginning, the vocational sector in particular has been plagued by systemic rorting, with scores of thinly veiled “visa factory” colleges offering low-quality — in some cases non-existent — courses.

Universities, where some populations are now edging towards 50 per cent foreign students, have likewise been accused of lowering standards.

“Labor did make some attempts to reform this process and diminish the rights of vocational students to change their status onshore,” Mr Birrell said.

“But rather than tightening the university level they actually opened it up, and so that set the scene for a very substantial flow of overseas students every year. And because the government allowed multiple ways for the students to stay on in Australia by changing their visa, as well as the right to apply for permanent residency, we got a chronic imbalance between the number of student visa arrivals and the number of departures.”

That imbalance was the “main dynamo” for generating the net overseas migration of around 250,000 in the 2010s.

“And Labor basically let it rip after 2022 which has produced these quite extraordinary figures of net overseas migration of around 500,000 in the last couple of years,” Mr Birrell said.

International cookery powerhouse

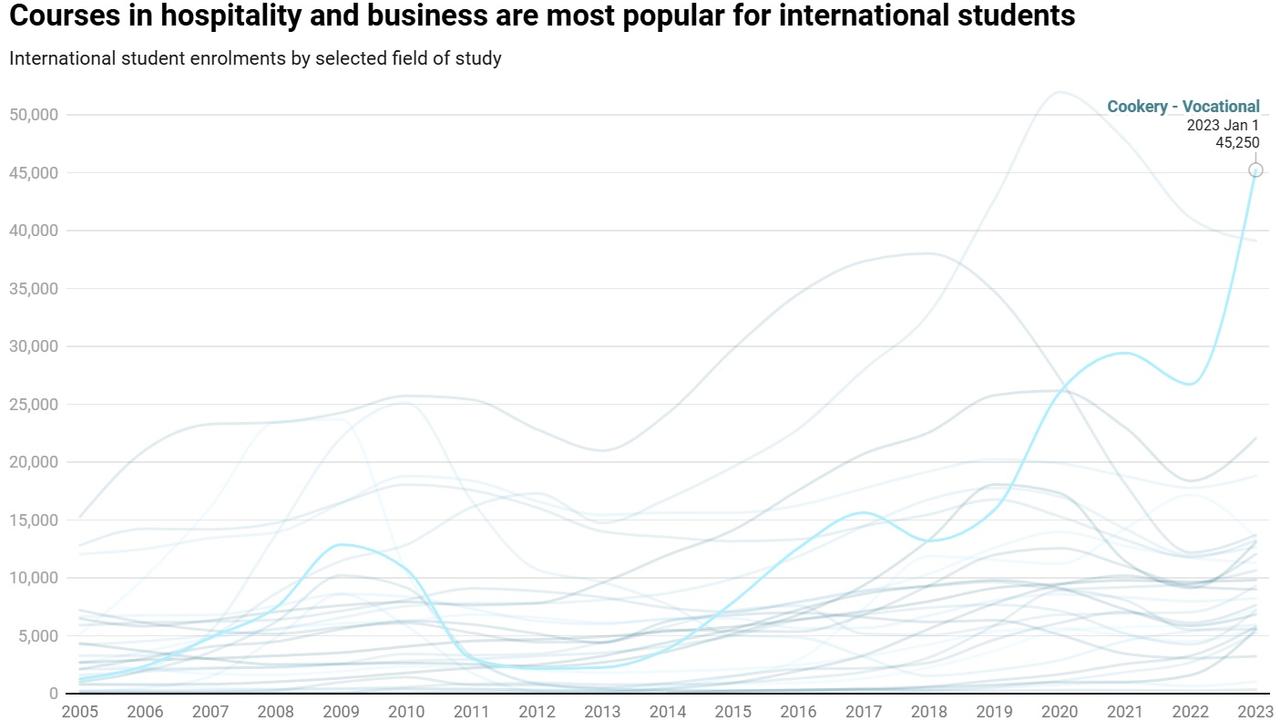

The result of all this is that, in just a few short decades, Australia has turned into a global leader in cookery courses and business management degrees.

Today Australia receives roughly one in 10 of the world’s estimated 6.4 million international students.

Last year a record 853,045 international students studied in Australia — equivalent to about 3 per cent of the population.

In 2005, that number was just 288,579.

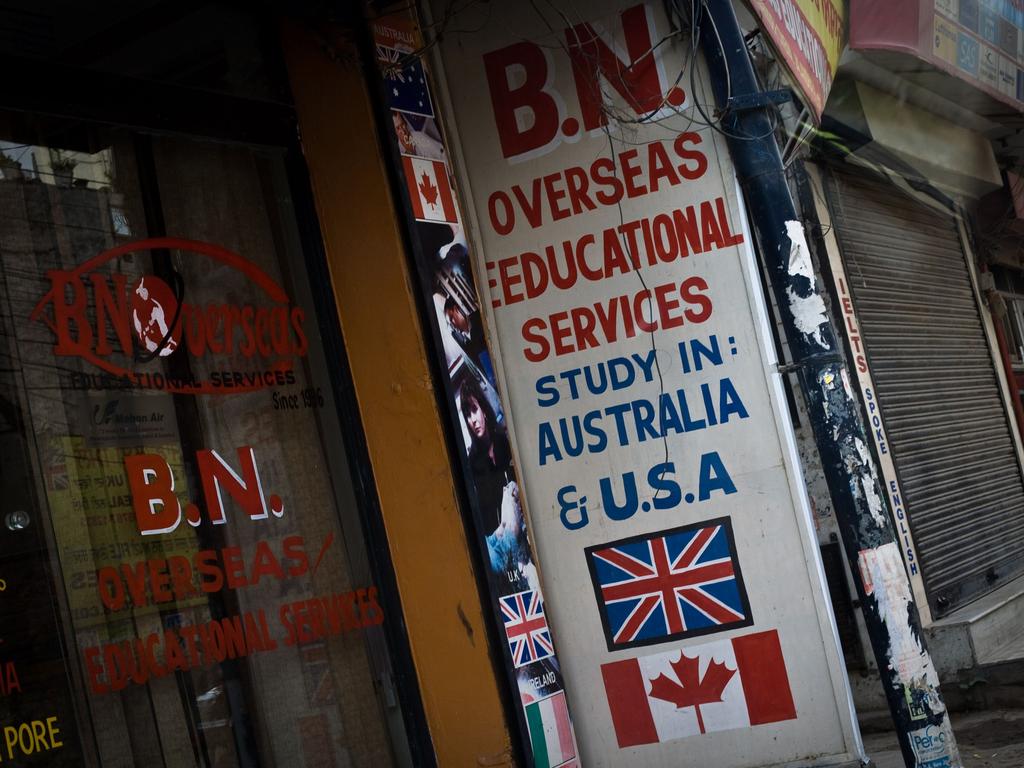

China last year remained by far the top source (189,282), followed by India (139,038) and Nepal (65,815).

Over the past two decades, the growth in international students from South Asia, and Nepal in particular, has been striking. Twenty years ago, Australia received just 1057 students from Nepal.

Over the same period, East Asian countries including Japan and South Korea — once the third top source — have seen sharp drops in numbers.

Australia today also receives fewer students from western countries. Just 7393 students came from the US last year — compared with 12,316 in 2005 — 4986 from the UK and 4003 from Canada.

It’s not exactly a secret that a large driver of the shift, and the reason Australia is so appealing as a study destination, is the generous work and post-study rights that come with a student visa.

Pathways to residency available for students who complete courses in occupations on skilled migration lists have driven much of the trend over the past two decades, particularly in the vocational sector.

In 2023, cookery was by far the most popular course for international students with 45,250 enrolments.

Business management was the second most popular vocational course with 39,127 enrolments, and the top choice for university students with 22,069 enrolments.

“International students are important to Australia’s society,” Associate Professor Peter Hurley and Dr Ha Nguyen from Victoria University’s Mitchell Institute noted in a paper last year.

“There are more international students in Australia than there are people living in Canberra. This brings enormous economic and social benefits. But this needs to be managed — for everyone’s sake.”

Billions of dollars at stake

Solving the international student dilemma going forward will require significant reforms.

International education is now described as a $51 billion export industry — a claim that has been disputed by some economists.

For the universities, the federal government faces the daunting prospect of weaning them off tens of billions every year in international student revenue to which they have grown accustomed.

“Which will inevitably mean some level of additional government funding, which is what they want,” Dr Rizvi said.

Labor last year tried legislating international student caps, but was defeated by the Coalition and the Greens. Labor then moved to plan B by slowing down visa processing, amounting to a de facto cap that has already led to massive budget and staff cuts at universities including ANU, UTS and Western Sydney University.

Peter Dutton has since proposed even harsher caps — the opposition leader is pledging to cut total numbers by 80,000, with a cap of 240,000 overseas student commencements each year. Public universities would be limited to 115,000, with 125,000 places available for the vocational, private university and non-university higher education sectors.

Universities make up only 43 per cent of international student enrolments but take in about three quarters of the revenue, as they charge average tuition fees of $41,000 per year compared with $13,000 for a typical vocational college course.

Capping international students at 25 per cent of the student population would deliver a crippling blow to some of the country’s top universities.

The University of Sydney, which has the largest proportion of international students at nearly 50 per cent, would stand to lose close to $900 million a year.

Collectively the large universities would be forced to cut 80,000 students, at a cost of $2.9 billion in lost revenue, according to analysis by the Mitchell Institute.

Group of Eight (Go8) chief executive Vicki Thomson said the plan “makes no sense on any level”. Universities Australia chief executive Luke Sheehy said it would “take a sledgehammer to one of the nation’s biggest income generators”.

National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) national president Dr Alison Barnes blasted the policy as “reckless”, saying it could cost the economy $5.8 billion and lead to thousands of job losses.

“Both political parties seem to think student caps are a good idea, but student caps are poor policy,” Dr Rizvi said.

A better solution?

Dr Rizvi recommends instead tougher evidentiary requirements and better screening to weed out non-genuine students, ultimately achieving the same result.

To take a step back, it’s worth explaining how the current student visa process works.

While the Department of Home Affairs is ultimately responsible for issuing visas, the educational institutions play a key role as they must vouch that the students are “genuine”.

“In many ways, an international student is purchasing a multi-year visa just as they are purchasing a course,” Prof Hurley and Dr Nguyen write.

“This is not normally a problem as migration and international education are closely intertwined. But issues arise when institutions act more as pathways to visas rather than education experiences.”

Each institution is rated either high, medium or low-risk by the government, based on various factors including whether it enrols a lot of students from high-risk countries or regions.

More prestigious universities like the Go8 are generally rated lowest risk, while vocational providers face the most scrutiny.

With the government facing pressure to curb numbers, visa refusals spiked sharply last year, led by massive declines in the vocational sector where approval rates plummeted from 77 per cent to under 63 per cent.

But the system remains demand-driven and largely uncapped, meaning visa refusals are forced to do the heavy lifting.

So while it may appear from the outside that no one is in control, Dr Rizvi said responsibility falls to the legislators.

“The bureaucrats stamping the visas are stamping simply based on the laws the government has passed — they can’t do anything else,” he said.

“It’s the government that’s got to [reform the process]. That’s where the failing is.”

Dr Rizvi recommends moving to an “ATAR-style system” for overseas students. “Make them sit a government-mandated exam,” he said.

But the vocational sector, Dr Rizvi argues, should be all but banned from offering courses to international students aside apart from a small number of areas with major long-term shortages — most obviously construction trades.

“I would certainly continue to tighten policy on those VET colleges, which to be fair the government has done quite significantly — many of these colleges are already facing financial ruin,” he said.

“They’re all low-quality courses in areas where we don’t have shortages. What’s the point of that?”

Professor Hurley and Dr Nguyen made a similar suggestion last year.

Their proposed formula for caps would prioritise institutions with significant domestic student enrolments to maximise the benefit to Australia. Conversely, hardest hit would be the largest vocational providers, which cater almost exclusively to international students.

“We estimate that the formula would mean at least 60,000 fewer international students at private vocational colleges,” they write. “This should be allocated to institutions who have a higher proportion of domestic students.”

1.1 million ‘sloshing around’

As things stand, the current system is bit of a mess.

Reaching Labor’s promised long-term net overseas migration target of 230,000 per year “will not be easy”, Dr Rizvi warned.

“They assume a massive exodus of students and temporary entrants, you can’t achieve that without further policy tightening as well as a tight labour market,” he said.

Every year around 20,000-25,000 former students are granted permanent residency.

“But the number sloshing around in the system is much, much bigger,” Dr Rizvi said.

“You’ve got a bit over 700,000 on student visas in the country and another 100-odd-thousand on bridging visas. Then you’ve got about 25,000 students at the Administrative Review Tribunal (ART).

“Then you’ve got temporary graduates, about 220,000 of those. Then more temporary graduates in the bridging visa queue. Then there are temporary graduates who’ve found their way onto a temporary skilled visa. Then there’s temporary graduates who have applied for asylum.”

Add them all together “and you get to about 1.1 million”.

“Our current student system really doesn’t manage that situation very well at all,” he said.

And that’s not to mention the growing backlog of those whose asylum applications have been refused by the ART, but won’t leave. The Home Affairs Department estimates around 70,000 people are in the country unlawfully — mainly visa overstayers or those who have had visas revoked or refused.

According to Dr Rizvi, deporting those people is harder than it sounds.

“There is a group of undocumented, but the solution to that is not simple, as Mr Trump is finding out,” he said.

“Unless you go about it in a very carefully planned and well funded manner, you’ll just end up with a bloody nose.”

The problem is “more than just manpower”.

“You have to think through the many dimensions of this,” Dr Rizvi said.

“You won’t locate many of them, that’s the first problem. Locating these people is not easy especially in a country like Australia. Secondly you have to detain them for a long time while they go through the legal process. Then you have to effect deportation. Added together the cost is eye-watering — we’re talking about tens of billions. You have to find a cleverer solution.”

Ultimately, there are three options.

“There will be some you can deport, some you [encourage to] self-deport, and for others find a sensible pathway for them to regularise their status,” he said.