Glaring flaw in Australia’s housing policies exposed as $20 billion spend backfires

A decade-long effort involving tens of billions of taxpayer dollars has failed to solve our housing crisis. This is why.

Australian governments’ multi-billion dollar efforts to help first homebuyers enter the property market have been hampered by a glaring flaw, which has only pushed up house prices and left those in greatest need of assistance at an even worse disadvantage.

That was the key takeaway from fresh research published by the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute this week.

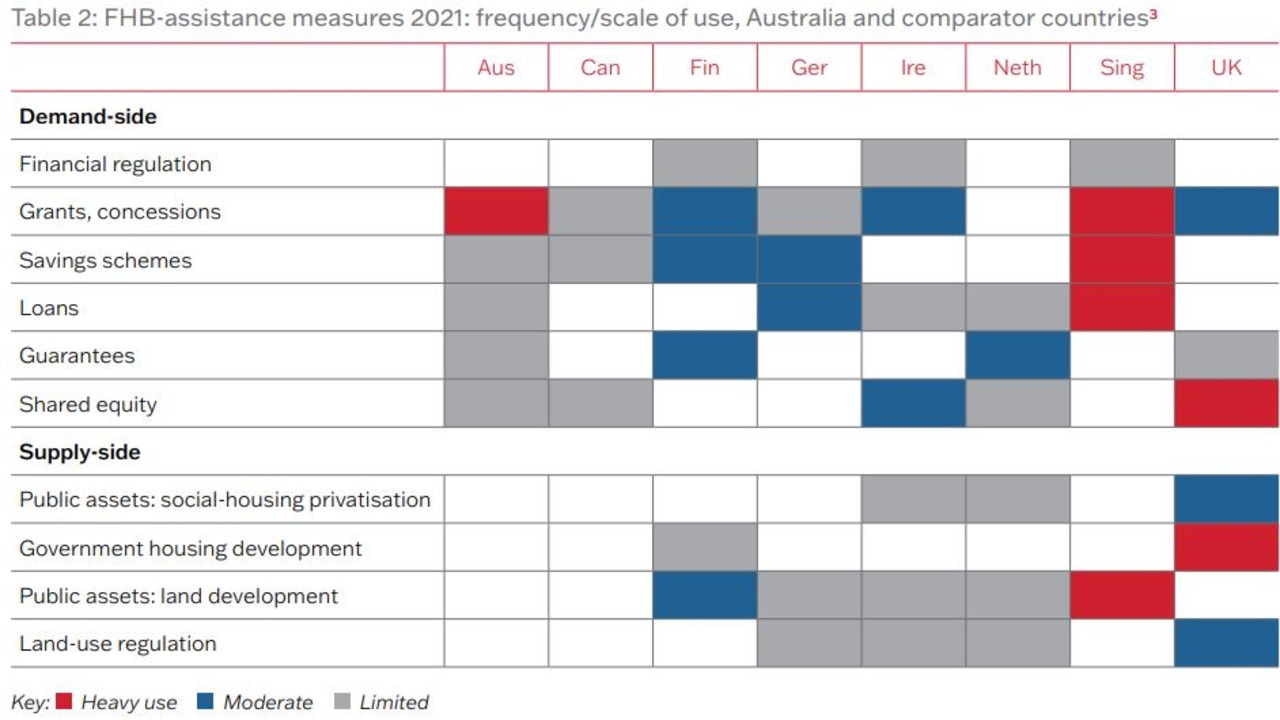

Scholars from the University of New South Wales, University of Sydney and RMIT University, with funding from the federal, state and territory governments, examined the suite of first homebuyer assistance schemes in Australia and compared them to measures adopted in seven other nations: the United Kingdom, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Canada, Finland and Singapore.

They found that Australia’s first homebuyer policies were “extremely one-sided”, with the overwhelming majority of programs focusing on demand instead of supply.

And by pumping up demand without simultaneously addressing supply, those programs have caused higher prices.

Some first homebuyers have benefited – mainly those who were already close to being able to afford houses on their own – as have existing homeowners and property investors.

However the bulk of would-be first homebuyers have been left behind.

“When 21st century Australian governments assist first homebuyers, they do so with demand-side schemes that feed further house price increases – and in turn spur calls for more help,” the study’s authors write.

“The present research estimates that more than $20 billion was spent this way by Australian governments over the past decade, allowing households already close to attaining ownership – including, in a growing number of cases, by virtue of gifts and loans of parental wealth – to set a new, higher price in the market.

“Where some see first homebuyer assistance as middle class welfare in relation to the socio-economic position of the direct recipients, it assists none so much as existing homeowners, as both vendors and holders of housing assets.”

A decades-long shift in policy

The study identified only a handful of “notable” supply-side first homebuyer initiatives that are currently operating, or are under serious consideration, across Australia.

One of them is the ACT’s Land Rent Scheme, which allows people to rent land on which to build a home instead of purchasing it. That reduces the upfront costs for them.

The South Australian government has used its planning powers to require developers to provide a quota of homes at an affordable price point.

Then there is the idea of Build to Rent to Buy, proposed by the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation, which seeks to enable aspiring homebuyers to rent a place while also accumulating equity in it.

“All of these appear to have strengths that should commend them for consideration by other Australian governments,” the authors note.

Otherwise, the major focus of both federal and state governments has been on demand-side schemes such as cash grants, mortgage guarantees and tax concessions. These policies increase the purchasing power of potential buyers without creating more supply. Hence, price hikes.

It wasn’t always thus.

The study notes that, between 1945 and 1975, “large scale state support” for homebuyers included major supply-side initiatives, which were “undoubtedly instrumental” in causing the home ownership rate to rise strongly.

“Importantly these interventions included major supply side programs – especially direct housing build-for-sale provision, as well as public rental housing privatisation. While largely implemented by state governments and their agencies, these were substantially led and financially supported by the Commonwealth government,” say the authors.

“Such measures were importantly complemented by large scale demand-side assistance, especially in the form of state-backed concessional mortgages, as well as by regulatory preferencing for first homebuyer lending.

“However, over the past 30 years, in tune with the dominant neoliberal mode of governance, the focus has shifted almost entirely to demand-side assistance. The main emphasis now is on boosting first homebuyer purchasing power through cash grants and cash concessions, and on enabling access to low deposit loans.

“Because they enable a marginal first homebuyer to outbid others and set a new, higher price in the market, they fundamentally increase house prices. By comparison with some comparator countries, Australia’s approach is extremely one-sided.

“Unlike some of the counterpart governments in the UK and elsewhere in Europe, Australian authorities have in recent decades largely chosen to eschew mechanisms that directly subsidise or otherwise enable the supply of homes suitable for (or reserved to) first homebuyers.

“Similarly, again in contrast with at least two of our comparator countries, Australia now makes no routine use of financial regulation powers to restrain established owners and investors from out-leveraging and outbidding first homebuyers.”

Current measures alone ‘will achieve little’

In the lead-up to the federal election in May, both major parties put forward housing policies aimed at helping people enter the property market.

The Coalition, under Scott Morrison, proposed allowing homebuyers to use up to $50,000 from their superannuation to invest in their first property.

“This would be like adding kerosene to a fire,” then-shadow treasurer Jim Chalmers said of the idea, arguing it would “supercharge” house prices.

Labor, meanwhile, proposed a scheme in which the government would take a share of the equity in people’s homes. Economists warned this, too, would push up prices.

“We have almost 60 years of evidence that, in my view, shows unequivocally that anything which allows Australians to spend more on housing than they otherwise would – be it first homeowner grants, stamp duty concessions, tax preferences for property investors, shared equity schemes – anything that allows Australians to spend more than they otherwise would results primarily in more expensive housing, rather than in more people owning homes,” Saul Eslake said at the time.

Both sides wanted to be seen to be doing something to help first homebuyers. Neither meaningfully addressed the core of the problem: established owners’ ability to price first homebuyers out of the market.

“We cannot hope to fulfil aspirations for sustainable growth in home ownership solely through adoption of more effective first homebuyer assistance mechanisms,” the study notes.

“Such measures are associated with the more general aim of enhancing housing affordability. However, this objective is in tension with the dominant theme of home ownership policy: to facilitate wealth accumulation through asset ownership.

“While the major tax and social security policy settings that support wealth accumulation continue to be treated as sacrosanct, measures that aim to assist first homebuyer access and affordability will achieve little.”

Australia ‘stands out’, and not in a good way

Driving home the point further, the researchers stress that Australia’s policy “for promoting home ownership” has morphed into “a policy of privileging homeowners”.

“Tax and transfer settings still encourage spending on home ownership, and liberalised housing credit has massively expanded the amounts spent, and hence prices, and hence the housing equity that existing owners can lever into spending on their own housing or, for that matter, rental properties,” they say.

“It is ‘as if increase of appetite had grown by what it fed on’, as Hamlet said of his parents’ affection for one another; a millennial Hamlet might say the same of his baby boomer parents’ proclivity for buying houses.”

“Unlike most of the international comparison countries, Australia stands out, as it overwhelmingly uses demand-side instruments and lacks a strategic framework,” added one of the study’s authors, Dr Chris Martin, from UNSW’s City Futures Research Centre.

“And unlike countries such as Finland and Singapore, Australian governments have resisted prioritising first homebuyers’ genuine interests by reforming tax settings that favour their housing market competitors: established homeowners and would-be rental investors.”

After ten years and $20 billion in taxpayer funds ineffectively spent, it seems that lesson still hasn’t been learned.