Coronavirus Australia: Where is the stimulus money coming from?

Suddenly the Government has been spending up a storm, dropping billions in virus stimulus packages – but where is this money really coming from?

The Australian Government is suddenly spending up a storm.

After dropping $18 billion in its first stimulus package, and $66 billion in its second package, it’s suddenly put the foot to the floor and announced an extra $130 billion in the third package. Then that’s been topped up with another billion for childcare.

As they say, “A few hundred billion here, a few hundred billion there, soon you’re talking real money!”

All this spending is designed to keep the current recession from being too sharp or going on too long. Nevertheless, it has some people nervous. Are we spending too much?

Permit me to reassure you. We can afford this. If needed, we can spend even more.

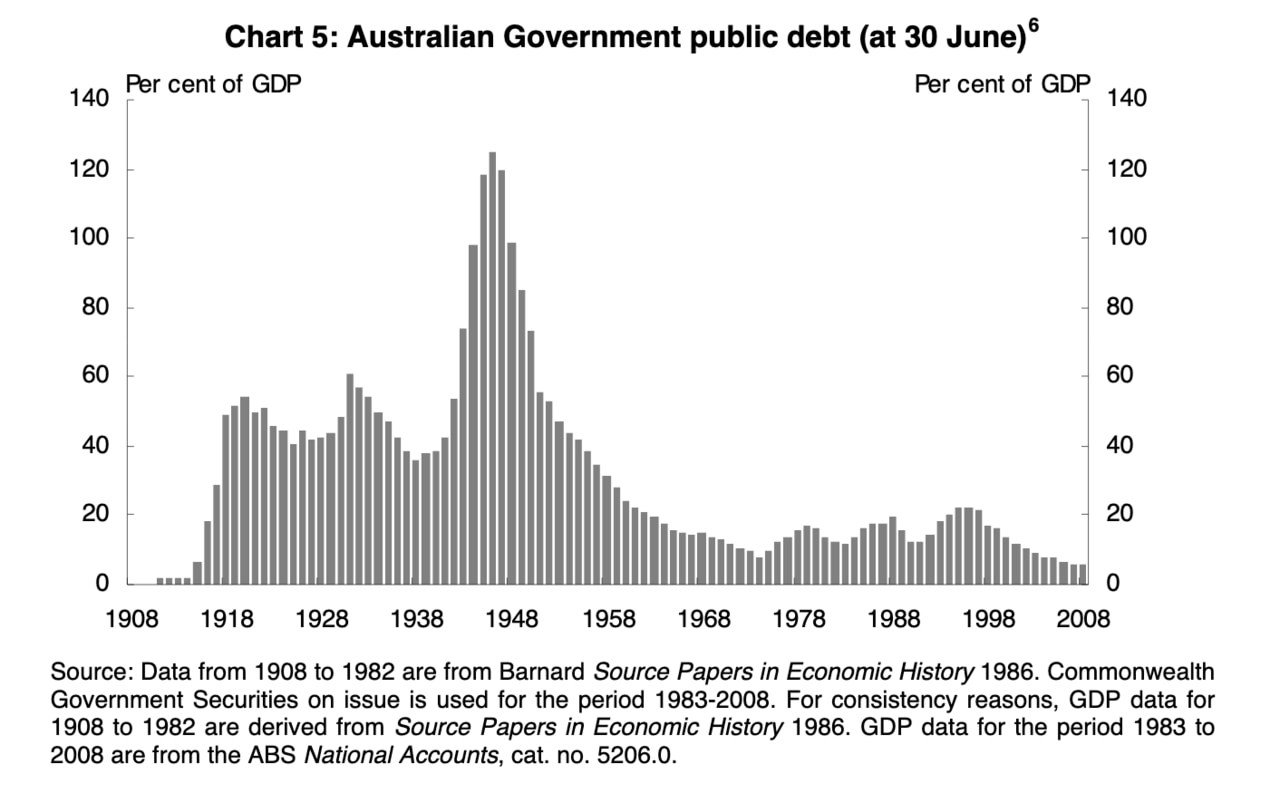

As the next chart of historic data shows, Australia’s public debt has been very high in the past – peaking in the Second World War, before falling to be far lower before the Global Financial Crisis. (Note, this chart stops in 2008.)

RELATED: Follow the latest coronavirus updates

RELATED: All the Australians who have died

Our net national debt looks modest compared to other countries. It is just 18 per cent – far lower than in the USA, where the comparable figure is around 100 per cent; or Japan, where net debt is 150 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

OUR BIG FAT ECONOMY

Australia has a $1.9 trillion economy. That’s nearly two trillion dollars, and it doesn’t just happen once. That sum flows through Australian hands every year. (GDP is like a river, not a dam. It measures a flow of money and things, not a pile of money.)

Our GDP is worth equivalent to $75,000 per person (this is what we call GDP per capita). Again, this is how much economic activity there is every year.

So when the Government spends an extra $130 billion in one shot in the middle of a desperate crisis, it’s not even that much, in terms of our economy.

Total coronavirus stimulus spending of $276 billion would represent 15 per cent of our economy. We don’t have to pay that off all in one shot. We can let the debt sit for ages, just paying the interest, if we so choose. That might be a good choice, because at the moment, interest rates are extremely low. This is a cost-effective point in history to go into debt.

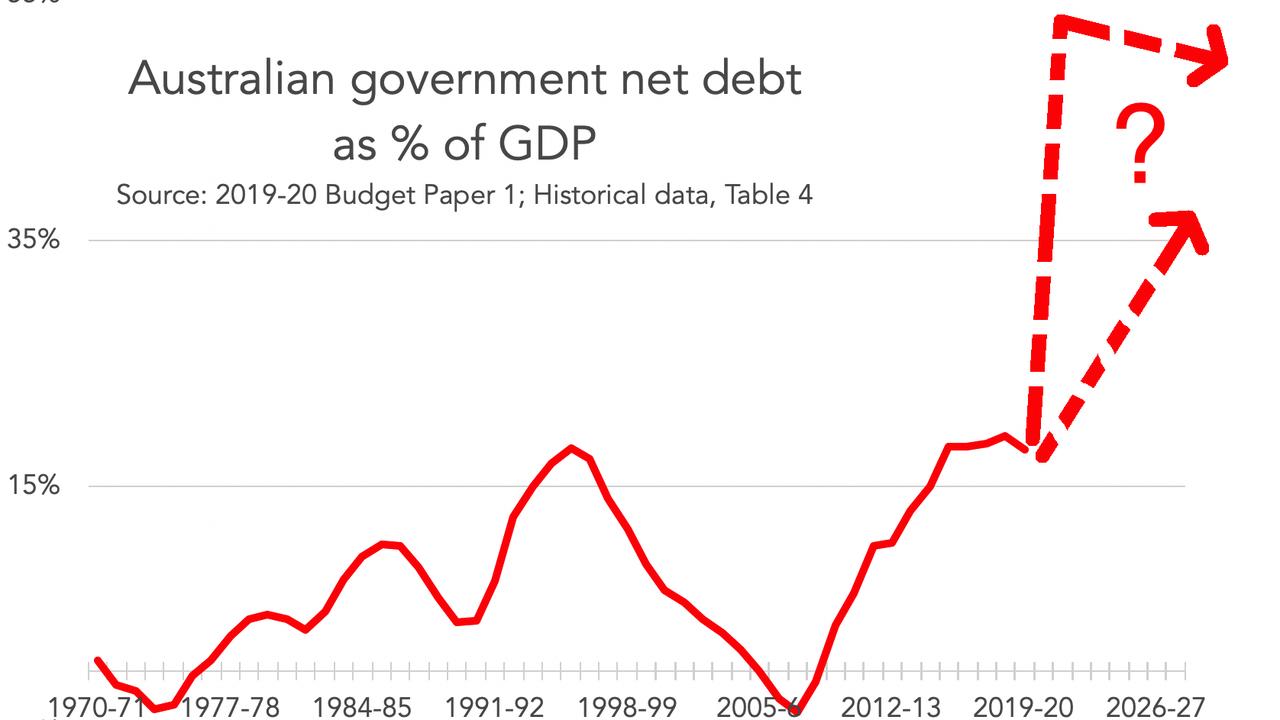

As the next chart shows, our current net government debt has been rising, but it is just 18 per cent of GDP. The Government can spend many billions more and still keep net government debt well below 100 per cent of GDP.

RELATED: How ‘flattening the curve’ saves lives

RELATED: How to apply for the Jobseeker payment

HOW DO WE PAY IT BACK?

There are two main ways you can make your debt go away, and a sneaky third way.

The main way we make debt go away is by paying tax. The Government taxes us more and spends less so it can have a surplus, and it uses that surplus to pay back the people we borrowed from.

You can see an example of this in the chart above – in the early 2000s, then-treasurer Peter Costello ran a bunch of surpluses and finally got the net debt to GDP ratio back below zero, just before the GFC.

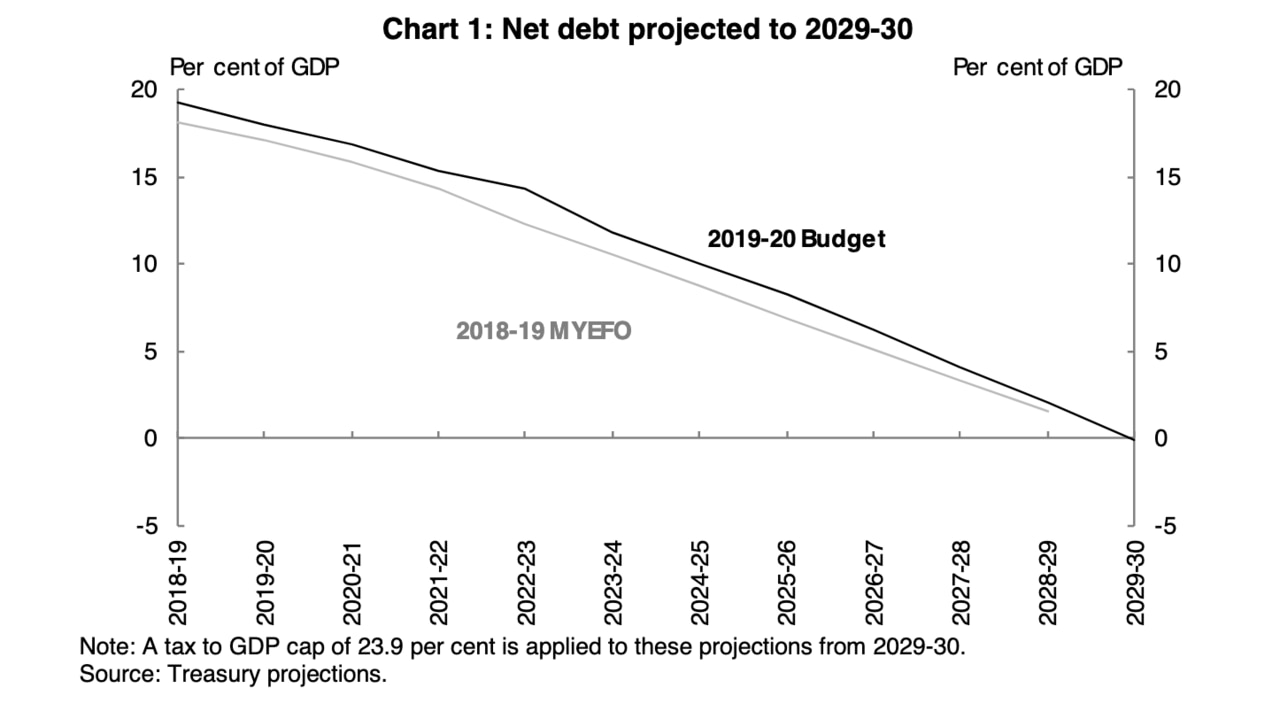

At the last budget, you will remember, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg was expecting a surplus. Running lots of surpluses was going to let us slowly pay off our debt, and the forecast looked like this:

This chart is now ancient history, of course. If we ever get to zero net debt it will be much later than 2029-30. And it will require a lot more surpluses.

This is the main argument against spending too much – today’s young people will pay higher taxes for the rest of their lives to fund the expansion in debt caused by extra government spending.

THE MAGIC OF INFLATION

The second trick for making debt disappear is inflation. While $200 billion might seem like a lot now, if we get some inflation over the next 30 years, it will shrink before our eyes.

Anyone who has a mortgage or a HECS debt knows what this is like. On the day you graduate or the day you buy your house, it seems massive. Twenty years later, the sums involved seem a lot smaller. If Australia’s GDP goes to $10 trillion in 30 years time, (which it would if we had 3 per cent growth and 2.5 per cent inflation every year), the debt we took on to survive this recession will seem much less significant.

This raises a key point about the ratio of net debt to GDP: You can make it get smaller by growing the GDP side of the ratio. And you can make GDP bigger using either economic growth or inflation. One reason Japan has such high debt ratios is its GDP hasn’t grown much since 1990. It has had both low growth and low inflation.

MMT

The sneaky third way to pay back debt is just printing money and giving it to your lenders. Governments can do that, but historically they have chosen not to, because it tends to cause hyperinflation. However, a variation of this idea is coming back into fashion, with a new name – Modern Monetary Theory.

One reason for the resurgence of Modern Monetary Theory is that the rich world has seen very little inflation recently – Australian inflation has been below the 2 per cent to 3 per cent target range for years. Why worry about inflation when we haven’t seen it for so long?

According to a recent note from Oaktree investment co-chairman Howard Marks, this crisis could shove Modern Monetary Theory into the mainstream.

“Possibly without serious vetting and a conscious decision to adopt it, Modern Monetary Theory is here,” Mr Marks said in a recent note to clients. Of course, the people who like this idea say it has the risks of inflation covered off. Expect to hear more and more about this the higher the national debt goes.

Jason Murphy is an economist | @jasemurphy. He is the author of the book Incentivology.