Charts proves Australians are working more for less

When two important metrics are put side-by-side it paints a picture of an Australia that is sliding backwards – and it’s not good for anyone.

We’re working more for less.

Australians are working more hours per person these days, reversing the previous trend of less work more leisure. But what have we got to show for it?

Australians work hours are rising but our GDP per capita is falling. We’re not even running to stand still. We’re running faster than ever and going backwards.

Let’s look at the data on working hours. Australia is doing more hours than ever as the next chart shows.

That’s cumulative. But work per person is also rising after a long trend of work hours falling, as the green line in the next chart shows.

It’s disappointing. I, for one, was looking forward to the three-day weekend! It certainly looked like we were heading in that direction. But the long trend of lower working hours for Australians has been reversing as our economy burns red hot.

Full-time workers are now more likely to be working over 40 hours, while part-timers are more likely to be doing 30+ hours.

And the bad thing about that? Our work is making less than ever. They measure this as part of the national accounts and it shows that the amount of GDP per hour worked is actually falling. Down a whopping 3.6 per cent over the year in the latest data. We used to get things done. Now, nope.

GDP per hour worked is important. It’s the thing that makes us a rich country. Any country can work their fingers to the bone. But real wealth comes from being able to create a lot with little effort. Australia has been good at that. Our people are skilled, our economy is efficient, and we have enough machines that for every hour someone spends at work, we generate a lot of output.

What makes our GDP per hour worked high? Machines. GDP per machine is not so high. But that’s fine, because machines don’t care about getting paid. (Technically economists call this capital, and it includes machines, cars, trucks, buildings, software, etc. All the things that help a person create a lot of output in a short amount of time at work. You can lift GDP per hour worked by spending money on capital goods.)

The amount of capital in our economy has grown significantly in recent years. But not enough to stop GDP per hour worked from falling.

What is going on?

Value-added falling right now is actually somewhat expected. The last few people you hire aren’t your best ones. Think about it like this: When you hire the first few people in an economy, the most important ones, the ones who run electrical power plants and deliver newborn babies, you get a lot of benefit.

But after a while you’re adding support people. A second bartender at the wine bar. A thousandth Uber driver circling the city. Another admin person. The value-add of the last few people you employ is less than the value add of the first few people. That means that the amount of value per person hired is falling. These people aren’t adding no value, they are contributing. But not contributing so much as some of the others.

Here’s an example: If we have nine workers who all make $100 of value an hour, the average person contributes $100 an hour. Then we hire a tenth person who provides $10 of value an hour. We have $910 of total value, or $91 per worker. The average GDP per hour has fallen.

The trick here is to try to make those last few people more productive. We want them to be achieving a lot. At the moment the Australian economy is adding workers who aren’t contributing a lot of value, and it means our nation is doing a lot of extra hours – contributing to more traffic on the road, etc – but without much extra to show for it.

But that’s not the whole story. It’s also about squeezing those existing workers harder. Making us do longer hours, even though we are probably not at our most productive when we work longer. It’s a lose-lose, and if we want to stay a rich country we need to get more productive, and make more with less, not more with more.

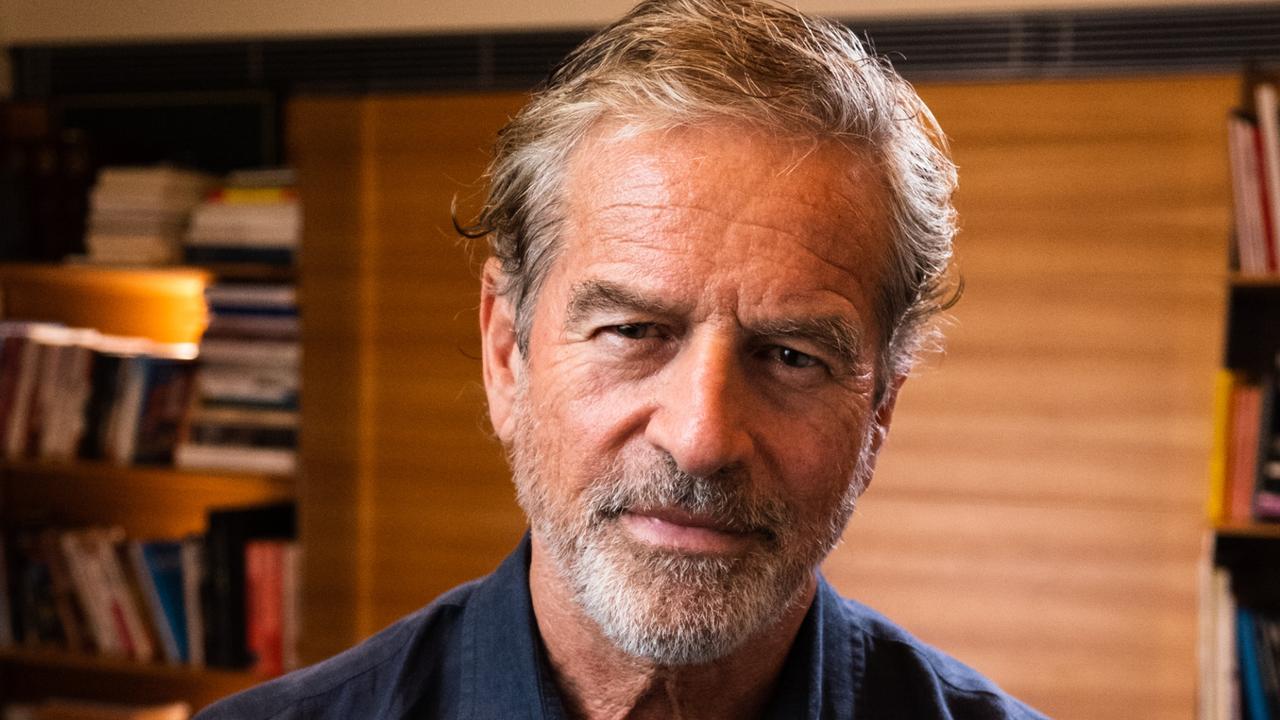

Jason Murphy is an economist | @jasemurphy. He is the author of the book Incentivology.