‘Can’t afford what they’re selling’: Why Australians all got $100 poorer over Christmas

The Australian dollar is falling fast. Families are already feeling the pinch – and experts say things are about to get a whole lot worse.

Well, we all got $100 poorer over Christmas.

The Australian dollar has gone from weak to weaker over summer. That makes us all poorer.

A weaker Aussie dollar is leaving Aussies with less buying power in global markets as 2025 lifts off.

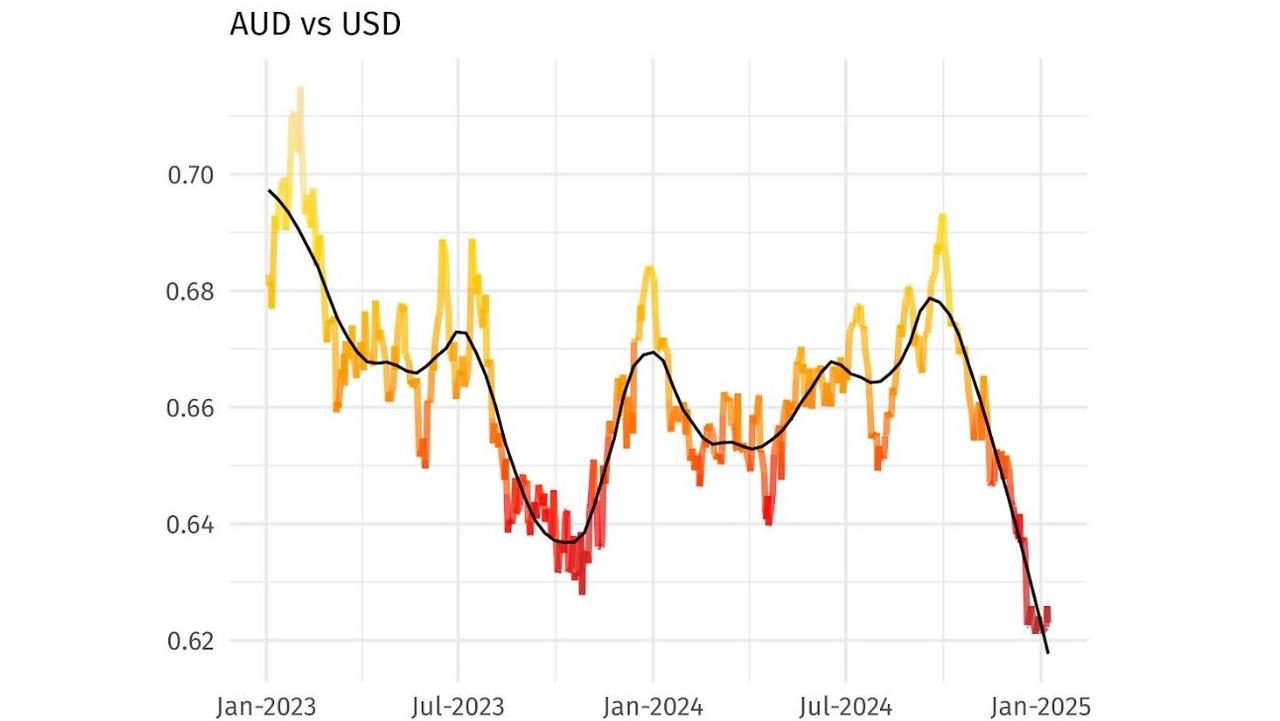

Our dollar had already fallen a lot from its lofty heights a decade ago, but the most recent period since December has really rubbed our noses in it. As the next chart shows, the Aussie dollar is down very sharply indeed against the US dollar, from about 66 cents to 62 cents.

That matters a lot for imports from America, and also for imports priced in US dollar terms.

It means our dollar is worth less and the things we buy now cost more.

The above chart shows our dollar against the greenback. Ever since Donald Trump won the US election, the Aussie dollar began to pale against its US counterpart.

But the issue is not just Mr Trump.

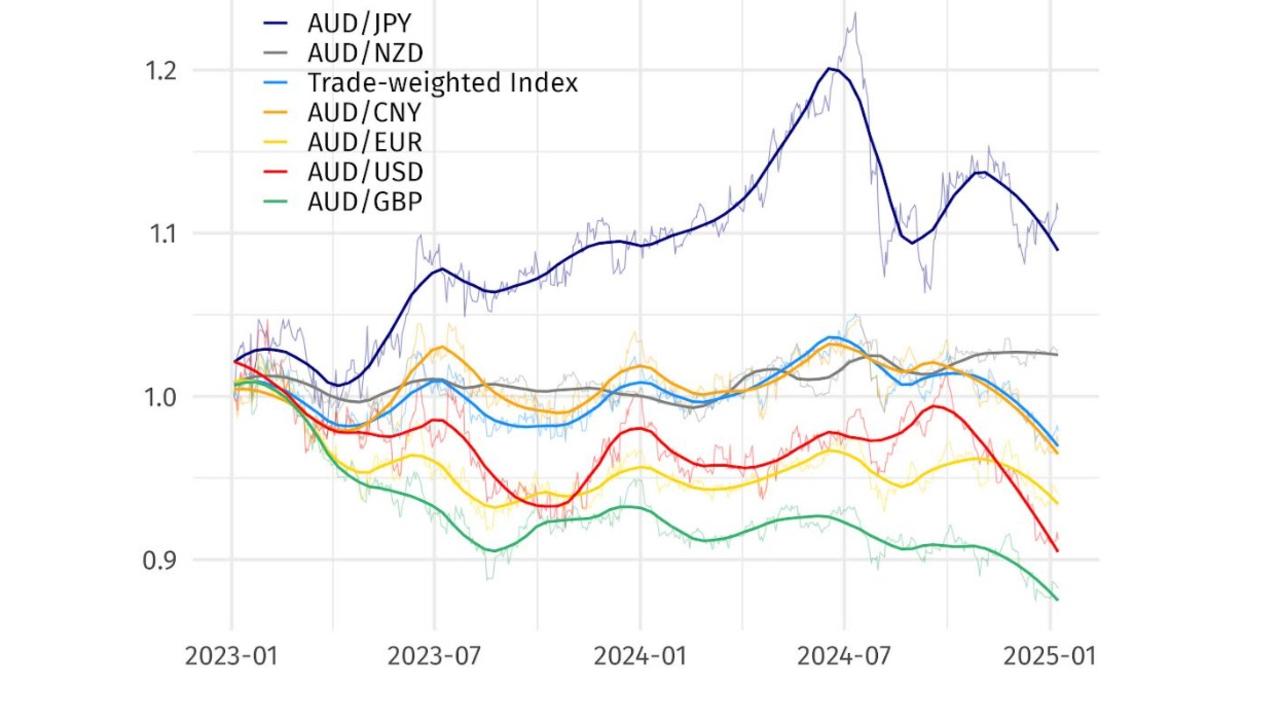

We’ve stumbled against almost every currency in the world.

As the next chart shows, our dollar is weaker in the last two years against all the major currencies except the Japanese yen and the New Zealand dollar. We are down against the Euro, the British Pound, the Chinese Yuan and the trade weighted index.

The loss in buying power in the last few months alone is worth a lot.

Australia buys $36 billion in goods imports a month. There’s about 10 million households. So that’s about $3600 in goods imports per household per month. Now our dollar is worth 3 per cent less (the trade-weighted index is down roughly 3 per cent in recent months), we’re talking about a hit of over $100 a month. And that’s without even thinking about services imports.

Of course, not all of this flows immediately through to purchases by households. Some of the goods imports are machinery for building roads, putting in factories, or intermediate goods that are put into other processes. But the higher costs of imports will certainly find its way to us eventually via higher prices or higher taxes.

It changes society

As 2024 came to an end, Japanese cars were absolutely dominating the sales charts. That’s partly because of the strength of our dollar against the yen. In a fairly grim 2024 car market, most countries sold fewer units than the year before.

Japan, however, blossomed. It sold 34,000 more cars in Australia in 2024 compared to 2023. Japan was already our biggest source of cars, but it is now approaching being fully a third of the market. And the exchange rate is a big part of why.

The opposite is happening for cars made in countries where our currency is weak. Car imports from America fell 14 per cent in 2024 and imports from England fell 12 per cent. We can’t afford what they’re selling, and probably they don’t want to send much product to us anyway, because the prices we pay don’t turn into much revenue in their own currencies.

Selling things to Australians is getting painful for foreign companies.

Any American company is looking at their Australian revenues and sighing. When we paid $A100 for an annual subscription to, say, Netflix, that translated to $US66 back in 2023. It is now worth $US62. They are probably thinking about price rises. Or, if they’ve already raised prices, they are probably thinking about doing so again.

Pump pain

When we talk exchange rates, we have to talk fuel. When I last filled up, it cost almost $2 a litre, and the currency bears some of the blame.

Fuel is one of our biggest imports, being used for both industry and private households. Oil is priced in US dollar terms on global markets. And when the price of fuel goes up, we don’t really vary how much we use, we just pay more.

Global oil prices are rising, yes, but the price is rising even faster in Aussie dollar terms, because our dollar is getting kicked so hard in global currency markets.

It’s not all bad

In economics, every trade has two sides. If prices are low, that’s bad for the seller, but good for the buyer.

Australian dollars are cheap, and that’s great news for people that want to buy Australian goods. Our exporters are going to be having a nice time. So if you work for one of them – perhaps Ansell, CSL or BHP, or maybe you’re a farmer or a tourism business – your job is probably safe right now. What we lose on household consumption we should gain back in extra demand for our products.

The job market in Australia is still tight, and lots of companies are still hiring. This could be the year you try to find a job at an exporter, and turn a falling dollar into something that works for you.

Jason Murphy is an economist | @jasemurphy.bsky.social. He is the author of the book Incentivology