Change to Scott Morrison’s home guarantee scheme proves glaring problem with first homebuyer programs

Scott Morrison says his recent housing announcement will make home ownership easier but instead it has exposed a glaring problem.

First home buyers may have welcomed news last week that the Morrison government’s popular guarantee scheme is set to be extended, but not everyone sees it as a good move.

Mr Morrison’s most recent announcement opens up the government’s popular Home Guarantee Scheme, which supports first home buyers to buy a property with a deposit as low as 5 per cent.

“We’re building a stronger future for Australians by making home ownership easier,” Mr Morrison said in a statement.

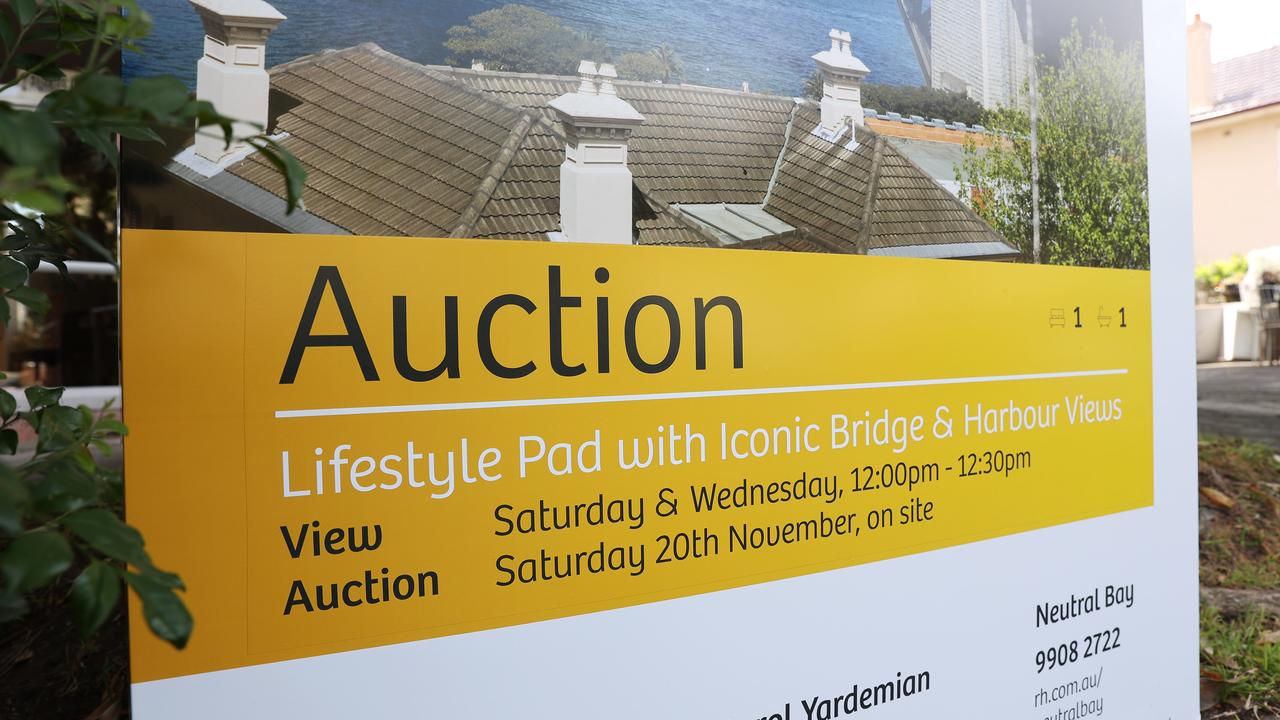

The scheme is a significant benefit in places like Sydney, where median property prices are now $982,000 (which includes units), according to realestate.com.au’s PropTrack home price index for March.

Currently the scheme is accessible to people trying to buy a property worth $800,000 in Sydney, but this will jump to $900,000 from July 1. Labor has backed the government’s move.

On average, home buyers need $196,400 in savings for a 20 per cent deposit, and a hot property market means ever-increasing prices often make it hard for buyers to save quickly enough to keep up.

It’s no surprise then that the government’s 5 per cent deposit scheme has been extremely popular.

However, a closer look at the scheme reveals the big problem it is perpetuating and how these types of programs are actually making things worse.

From next financial year, buyers in Sydney and other regional NSW centres will be able to access the scheme to buy a property worth up to $900,000 – up from $800,000 previously.

Many first home buyers may be welcoming the change – something Labor has also been pushing for – but it underlines the fact that buyers must now be willing to spend almost $1 million to buy their first property.

The situation facing first-time buyers in Australia is now so dire, economists are essentially saying the government should get out of the way.

Economist Saul Eslake said the expansion of the program would help some people buy a home, but the group that it really helps is existing homeowners because the value of their properties will rise due to the extra assistance from the government.

“What it (Federal Government) should be doing … is backing away from policies that needlessly inflate the demand for housing,” Mr Eslake told 3AW’s Tom Elliott.

Mr Eslake said Australia’s home ownership rate had been in decline ever since 1966, shortly after the Menzies government introduced the first homeowner grant scheme in 1964, supported by then-Young Liberals president and former prime minister John Howard.

“That was really the beginning of what’s been a downhill run because ever since then, governments of both Labor and Liberal persuasion, have, when confronted with complaints about falling home ownership rates, resorted to giving ever bigger and more generous, more widely available, first homeowner grants that end up in the pockets of … home vendors.”

Mr Eslake said state governments had also provided stamp duty concession, which in turn enabled buyers to pay more for a house because they don’t have to pay as much, or anything, to the State Government.

In addition to this, property investment became more attractive after capital gains tax changes Peter Costello and John Howard introduced in 1999.

“With the result that a significant proportion of housing finance that used to go to first homebuyers, instead went to investors who would be able to outbid first home buyers at auctions, thus forcing the people who might otherwise have bought their own homes to rent, and then (for homeowners to) claim that they deserve tax deductions because they’re supplying rental housing,” he said.

In reality, Mr Eslake said there was not a lot the Federal Government could do to boost housing supply, other than provide more grants, or provide loans to states and territories for social housing.

While Labor has promised to spend $10 billion to create 20,000 on social and affordable housing, Mr Eslake said there didn’t seem to be much enthusiasm on either side for the sort of social housing programs that were commonplace around Australia in the 1950s and 60s.