An end to racism and inequality: Could Uber and Airbnb save humanity?

RACIST cabbies and feral backpackers could be a thing of the past thanks to the one thing that makes the sharing economy so radical. But can it be trusted?

IT WAS the rating system that hooked me in.

When I finally decided to give UberX a go last month, there was a moment when I almost bailed.

The driver of the Mitsubishi Lancer was on his way, and the app was counting down the minutes to his arrival at my friend’s doorstep in Darlinghurst.

His name was Dale and a picture of his mug flashed onto the screen of my phone as his approach drew nearer.

It freaked me out.

No offence to Dale, but for some reason being able to see his face did nothing to dispel my hesitation at getting into a random stranger’s car.

But it was late, I was tired and as my friend pointed out, Dale could not be a serial killer because he had a 4.5 star rating.

The ride went without a hitch and I got home safely, easily and cheaply.

I was sold.

And for a moment, it seemed like the sharing economy had all the answers.

CAN THE SHARING ECONOMY MAKE THE WORLD A BETTER PLACE?

As Uber celebrates its 10 millionth ride in Australia today, the company is at pains to cement its reputation as a quick, safe and affordable transport option.

A fresh public relations offence has been launched as state and territory governments grapple with UberX’s disruptive power, with the ACT set to become the first to make ridesharing legal from October 30.

Speaking to news.com.au yesterday, Uber’s Australian general manager David Rohrsheim waxed lyrical about the company’s potential to reduce alcohol-related violence by getting revellers home safely, and close the gaps in our capital cities’ woeful public transport networks.

But among all of these details, one key feature underpins the app’s popularity and success: it removes anonymity from the equation. Both drivers and riders must rate each other after each trip, and either can be banned for bad behaviour.

And this seems to engender a level of civility and fairness that, unfortunately, is not guaranteed in old-school transactions.

“What really matters is just knowing that you’re going to be held accountable,” Mr Rohrsheim said.

“That just creates a different environment in the car, instead of two strangers bringing all their emotional baggage from the trips they’ve had before,” he said. “People tend to be on their best behaviour.”

THE UNCOMFORTABLE REALITY OF OUR RACIST TAXI SYSTEM

Swapping anecdotes with friends about awful taxi experiences, I heard the story of a man of Maori heritage who had spent his whole life unable to rely on cabs, due to his imposing physical appearance.

Cabbies would speed away from him on sight, despite his gentle and polite nature.

And he’s not the only one.

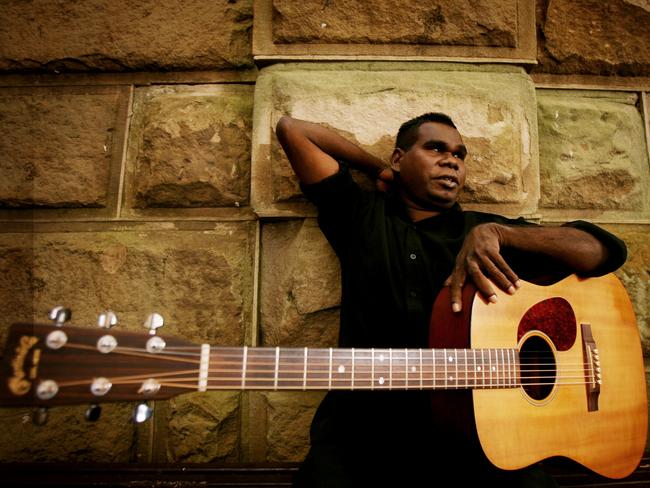

In April, two Aboriginal musicians were refused a taxi ride from their record label’s office in Darwin.

Djunga Djunga Yunupingu and Johnno Yunupingu, relatives of acclaimed Aboriginal musician Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu, were left standing outside Skinnyfish music not once, but twice by cabbies who refused their patron after being booked over the phone.

In 2012, Gurrumul himself was refused a taxi in St Kilda after performing at the Palais Theatre as part of his tour with Missy Higgins.

Then in 2013, a group of Aboriginal actors were refused service by four taxis — and racially abused on a tram — while in Melbourne rehearsing a theatre production.

It’s safe to assume that an untold number of such incidents, involving indigenous Australians who are not famous performers, happen regularly across the nation.

I’ve yet to hear a tale of an Uber driver refusing a ride based on the passenger’s race, and the platform arrival in Manhattan was gratefully embraced by African American customers fed up with the city’s “racist yellow-taxi cartel”.

But as Latoya Peterson asks in a piece written for Fusion: “What is to say that Uber won’t repeat the taxi industry’s flaws once they replace cab drivers as the incumbent mode of transportation?”

The contrast between the politesse of the sharing economy and the bigotry of the real world was illustrated earlier this month when American rapper STEFisDOPE checked into an Airbnb rental in Atlanta, Georgia.

Slate reports that a neighbour called the police on STEFisDOPE and their four MCs, assuming that a burglary was underway.

Yo! The Air B&B we're staying at is so nice, the neighbors thought we were robbing the place & called the cops! 😂 pic.twitter.com/XUQjuyCXMO

— Trill deGrasse Tyson (@STEFisDOPE) October 9, 2015UBER ASSIST: DISABILITY ACCESS IS A SENSITIVE ISSUE

It’s all well and good to revolutionise personal transport, but when a business model is based on making use of everyday Australians’ cars, there is not going be a huge benefit to passengers with wheelchairs.

But Uber has been doing its darnedest to promote itself as a purveyor of both accessible transport provider and enabled employment.

As part of today’s celebratory media release, Uber reveals that its drivers have spent a collective 100,000 hours on the road and available for wheelchair accessible rides — that an average of about 23 drivers available across Australia in any given hour, over the past six months.

The company would not reveal how many accessible rides were actually given.

Pushing to expand access would appear to be a wise move for the company, which is embroiled in a class action with more than 40 blind passengers in the United States.

Mr Rohrsheim told news.com.au that Uber was “firmly anti discrimination”, citing its inclusion of hearing-impaired drivers on the platform and the six-month-old Uber Assist program, which trains drivers in transporting people with wheelchairs.

“One in ten drivers have been through the training,” he said.

At least one passenger so happy with his Uber Assist experience that he wrote to the NSW Government taskforce that is reviewing the sector.

“As a gay young disabled man I have had shocking experiences with taxis, so much so that I never want to use them again,” he wrote.

“I have had many drivers over the last 10 years refuse to pick me up, they made offensive comments about my sexuality, they refused to help me with shopping bags or luggage or they didn’t want to go in my direction.”

By contrast, he said, Uber drivers had behaved professionally and were “sensitive to my needs, taking me on my trips to various hospitals to see my specialists.”

FROM THE MARKETPLACE TO ‘A COMMUNITY BUILT ON TRUST’

Much has been said about the potential for Uber and Airbnb to transform the way goods and services are delivered and consumed.

Rachel Botsman, who wrote the rule book on the sharing economy after spotting its potential in the late 2000s, predicts that it will transform the world “in ways that we can’t yet even imagine”.

Speaking at the Commonwealth Bank’s Wired for Wonder conference in Sydney, Ms Botsman said the sharing economy was more than just a marketplace.

The key to Airbnb’s disruptive power, she argued, was its ability to create “connected communities” based on human trust, where participants are held accountable to a standard of fair and ethical behaviour.

“The staggering thing about these rating systems is that you’re not just rating the host; they’re rating you as guests ... and the implications are enormous,” Ms Botsman said, giving the example of how she caught herself leaving towels on the floor of a hotel bathroom.

“I realised that I would never do this as an Airbnb guest, because of those damn ratings,” Ms Botsman said.

NOT EVERYONE RATES THE STAR RATINGS

Psychologist Sarah Godfrey says customer ratings are not as straightforward as they seem, especially when they are structured around a personal interaction.

She said concerns about how an Uber driver would be impacted by feedback were likely to temper the response.

“People tend to just want to be nice,” Ms Godfrey said.

“A lot of people will be thinking ‘will they find out who I am? What if I get in a car with him again? Will I make him lose his job?’”

It’s a pertinent question, as Uber drivers must keep their average rating above 4.4 stars or risk being booted from the platform.

As Quora user David Greenspan points out: “There’s a reason drivers all seem to have ratings in the high four-to-five range. This is not grading on a curve; you will not be picked up by a three-star driver.”

Dozens of drivers have taken to the Uber Facebook page to protest the ratings system, complaining of unreasonable customer requests, unfair ratings by drunk passengers and poor communication from Uber about why their accounts had been deactivated.

“I tried my best to do all I can do to provide a five-star service to the riders, but some of them still rate me four or less,” one driver wrote.

“It seems to me, some of them don’t really understand the concept of the stars that Uber is using.”

Writing on Quora.com, former UberX driver Scott Banks said the company’s tips for maintaining a five-star rating — like opening the door for customers, providing free bottled water and mints — were “useless” and that ratings were skewed by factors beyond drivers’ control.

But Mr Rohrsheim said it didn’t matter that people’s perceptions of a five-star ride were different, as it all averaged out.

“The beauty of the five star rating system is it’s very familiar for more people, so we don’t need to explain it,” he said.

“It’s okay that we have different standards, as no one person’s rating decides whether a driver is good or bad.”

New Yorkers, incidentally, are among the harshest scorers in the world, he said.

‘SOCIOLOGICAL FACTORS’ AT WORK

It could well be that a lower-than-deserved rating is the least of our worries.

A Boston University research paper published earlier this year found that travellers were more generous when reviewing Airbnb properties than hotels or holiday houses booked on traditional platforms.

Based on analysis of more than 600,000 Airbnb properties, the study found that almost 95 per cent had an average user-generated rating of either 4.5 or 5 stars — and virtually none scored less than 3.5 stars. Over on Trip Advisor, the average rating for comparable properties was a humble 3.8 stars.

“Perhaps sociological factors are at work, whereby individuals rate other individuals differently or more tactfully, than they rate firms such as hotels,” the authors said.

Ms Godfrey said being in proximity to a service provider, like an Uber driver or AirBnb host, made people more likely to give a “fake good” response.

And, she said, the fact that users were forced to leave a rating meant that some would not take the process seriously.

“If I can’t opt out or in, then I have less investment in the rating scale and don’t take it as seriously,” she said.

Most customers would go for a score of about 50 per cent if put on the spot “if they were not particularly impressed or distressed”, she said.

When all’s said and done, maybe a tactful and gracious assessment is not such a bad thing if the experience was basically good, and based on human connection. After all, isn’t that what makes us happy?

I still haven’t worked out how to rate my last Uber driver, who typed the wrong suburb into his GPS and took me on a 6km detour.

He was super nice, and I figured it was partly my fault for not paying attention when he zoomed past the freeway exit.

I definitely don’t want him to lose his job, but I don’t really want to give him five stars either.

And there’s just something about hitching a ride in a stranger’s car that makes me feel like I should be grateful.