‘You’re paying too much’: Sneaky Aussie supermarket tactic revealed

An economist has lifted the lid on an extremely sneaky tactic the supermarket giants are using to manipulate us – and line their pockets.

There have been some big revelations recently about supermarket pricing.

And amid all the furore, there’s a really important thing to remember – often, the sale price is the real price.

Let me explain.

Supermarkets put things on special periodically. They sell more when the price is low, and less when the price is high.

And some things barely sell at all when the price is high.

It might be called the recommended retail price, but for certain types of items, the RRP is actually more of a Really Rare Price.

Most sales happen at the low price, the “special” price.

For my household, this is definitely true for Lindt chocolate and Vaalia yoghurt pouches. I never buy them at full price, but I always buy them if I see them on special. And it turns out, I’m not alone.

Meanwhile, as of Thursday, legal papers have officially been filed against both Coles and Woolworths on behalf of customers regarding alleged dodgy sale prices, with Sydney-based firm GMP Law lodging the lawsuit in the Federal Court and claiming consumers who join could get refunds ranging from $200 to $1300.

It comes after the ACCC last month alleged both grocery giants temporarily increased prices by at least 15 per cent before then adding promotional discount stickers to more than 200 products with prices higher than before the hike.

Profits and specials

But back to the sale price being the real price.

Imagine an item that costs $6 at normal price and costs the supermarket $2.50 to get in.

If they make a sale at full price, they pocket $3.50 in profit. But when the price is $6, the item barely sells – maybe just a couple of units a week.

So they knock it down to $3. That’s 50 per cent off. Now, customers get excited. We buy 10 items while the item is on sale, delivering $0.50 in profit on each one. That’s $5 in profit, actually more profit from selling higher volumes at a lower price than they got from selling fewer items at a higher price.

This is just a theoretical example – supermarkets are extremely secretive about their profit margins – but it helps us understand the dynamics and why they make the decisions they make.

Importantly, while this example is theoretical, it matches the actual data.

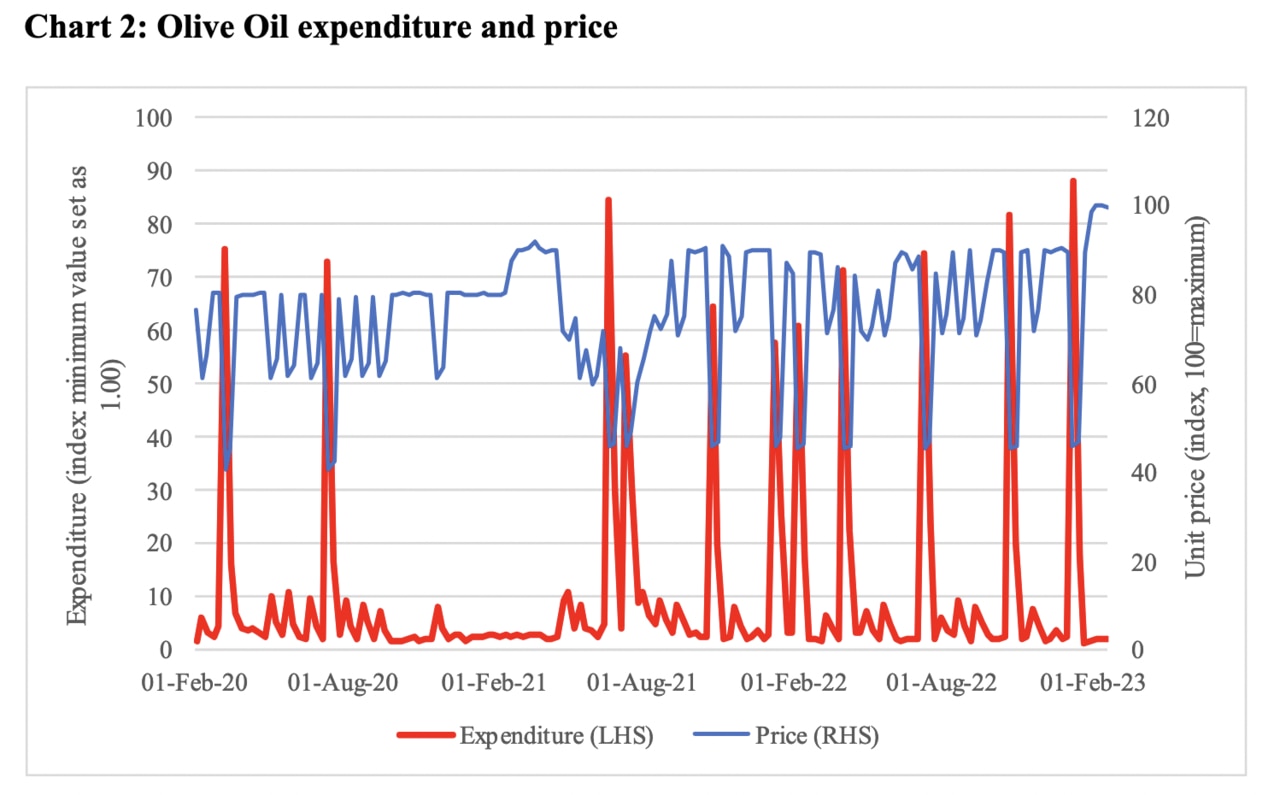

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) has done a huge amount of research on this, and it published an astonishing graph on one item that sells way more when it’s on sale than when it’s full price – fancy olive oil.

What this chart tells you is that if you pay full price, you’re a bit of a sucker. Most people only buy this thing on sale.

If you look at the chart, the red line shoots up whenever the item is on sale. When it’s on sale, it can sell over 80 times as much volume as when it is full price.

That means most people bought their oil at the sale price, and so the sale price is the real price.

“When the price is normal, very little is purchased,” the ABS said.

Big brands

It’s important to understand that these strategies aren’t happening against the will of the supplier. This pattern is being applied to big brands that are in strong negotiating positions.

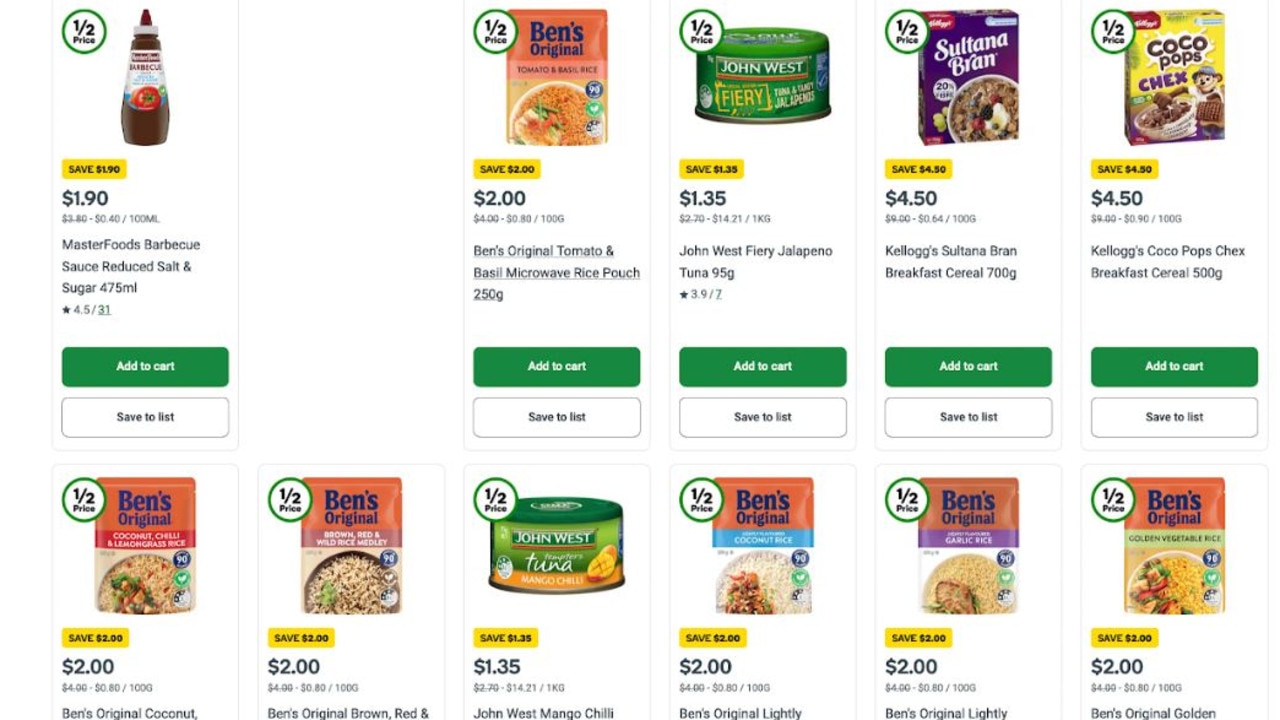

They are in on it – Cadbury, Kellogg's, Mars, etc.

I see lots of major brands in the 50 per cent off section of the Coles and Woolworths websites.

Supermarkets can make supply agreements with these big dogs that include everything – how much product they will supply, which shelf it goes on, whether it gets a fluttering tag that says Prices Dropped, what part of the website it shows up in, whether they get a poster on the wall or an end-of-aisle display, where in the catalogue the products show up and of course, how the discounting pattern works.

Data on how much they sell at full price versus on special will feed back in to how the specials are set next time.

I know if there’s been a long gap between specials, I react more strongly next time something gets a price cut. Leave Doritos at full price for three months, and I will go crazy when you next knock them down to half price. I bet you the supermarkets are feeding data on that into their profit-maximisation model.

I asked Coles about all this, and their spokesperson’s answer didn’t give much away.

“There are many factors which help us decide if and when to put items on special, including seasonality, availability, supplier preference and frequency of purchase,” they said.

Woolworths was also approached for comment, but declined to provide a statement.

Optimised

Don’t think they are knocking 50 per cent off these prices because these things are near their use by date. It’s part of a strategy to maximise profits. $4.50 for Coco Pops doesn’t seem like amazing value, except if the usual price is $9. Then it makes you want to swoop in and buy them.

Some items simply don’t sell at full price. Certain things “basically only sell when they are on sale”, an expert who has seen all the data told me. But those are mostly shelf-stable goods, like chocolates and shampoo.

The discounting strategy is not one supermarkets use much on fruit and vegetables. It is one they use much more in the confectionary aisle. I’m no stranger to getting sucked in like this.

When the Old Gold or the Lindt blocks are all covered in big yellow tags and they’re half price? I fill the trolley.

Another item where I am especially susceptible to a deal? Yoghurt pouches for my kids. 50 per cent off Vaalia? Lovely, thank you. I buy handfuls.

And many of us are the same.

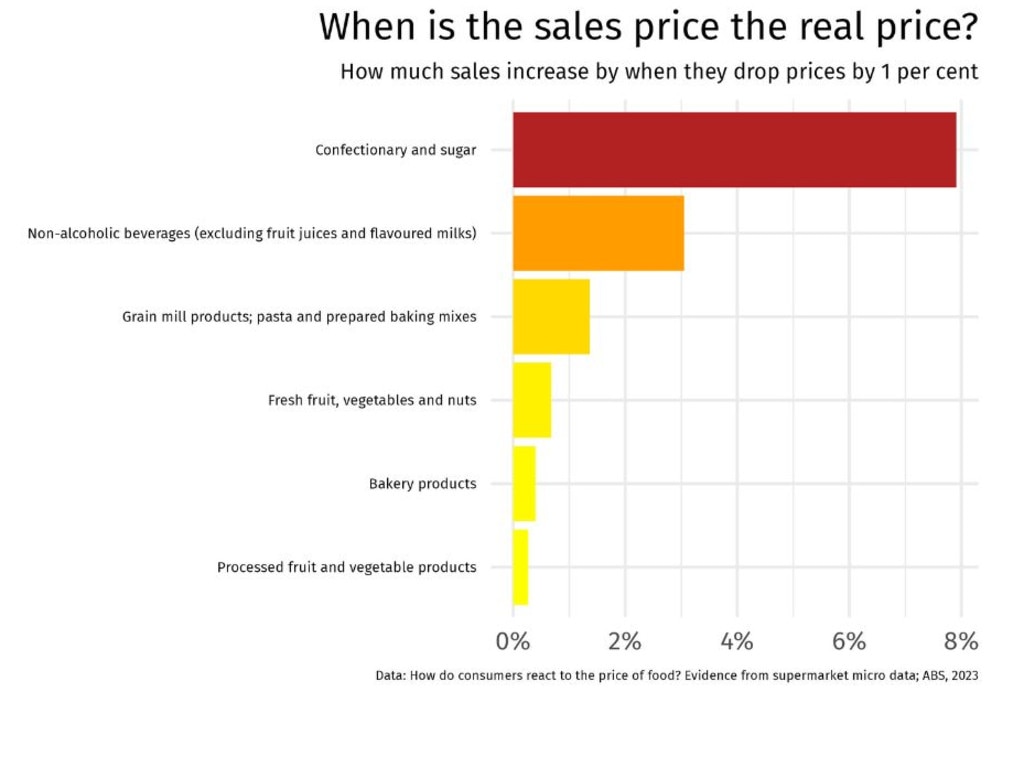

The ABS has done the research on what products we go crazy for when they are on special.

We react moderately to specials on baked goods, medium-strong to specials on soft drinks, and we enter a state of wild frenzy when there is a special on confectionary. We will buy 7.9 per cent more whenever the price falls by 1 per cent, implying that a 10 per cent discount would drive sales up by 70 per cent.

It would seem like these products sell far more when they are on special than when they are at full price. I’d argue that for a lot of chocolate and confectionary, the sale price is the real price and the “normal price” is little more than a psychological trick.

For example, they want us to think Lindt is a $6 for 100g brand. That’s the shelf price a lot of the time. But in terms of what I actually pay for Lindt blocks, it’s a $3 for 100g brand. because I only buy it on special. And I suspect a lot of you are the same.

Supermarkets are very tight-lipped about their data, but a Melbourne-based hacker called Adam Williamson has collected some public price data and figured out the pattern of how specials work.

You can add his software to your internet browser and when you go to a supermarket’s website, it will tell you about the history of the price of that product.

It’s worth keeping an eye on. Because if you’re paying more than the sale price, you’re paying too much.

Jason Murphy is an economist | @jasemurphy. He is the author of the book Incentivology