Myer job advert proves Australia is cooked

As cost of living pressures bite, Aussies are resorting to new lows and major retailers Coles, Kmart and Myer are feeling the impact.

Shoplifters are wreaking havoc on Australia’s retail sector, with the theft epidemic getting bad enough that Myer has had to report it to the stock market.

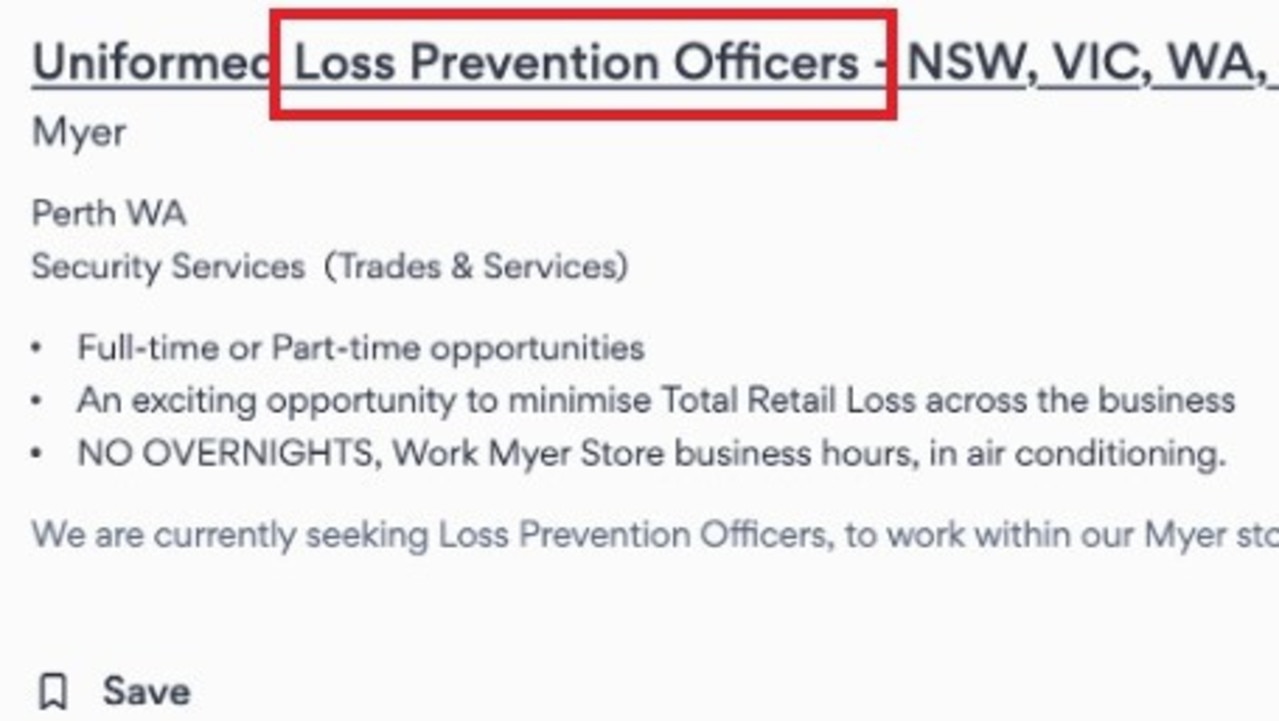

The upscale department store came clean to investors via its annual report, admitting theft is now bad enough that it is affecting margins. Myer is also hiring dozens of security guards to patrol the shelves.

Profit margins fell thanks, in part, to “the unfavourable impact of higher shrinkage,” Myer said. Shrinkage includes, but is not limited to, theft. It said operating gross profits would have been higher if not for $12 million in “increased shrinkage”.

Myer’s annual report promises to make “investment in loss prevention resourcing to aid shrinkage reduction”. That means hiring security guards, and that’s exactly what they’re doing, to judge by job ads on a major website.

“We know that shrinkage is an issue affecting all retailers and we have for many years worked with police across the country, as well as the retail industry, to reduce the occurrence of shoplifting in our stores,’ said a Myer spokesperson.

“In addition to plain clothes and uniformed security, Myer uses a number of technologies including merchandise protection tags.”

Shrinkage includes theft, but it is not just theft. It is breakage too. And in fresh food stores, shrinkage includes things that went off before they could be sold. And of course, theft is not just shoplifting by customers. Staff pinch things too.

Is it built into the prices?

Of course, a certain level of shrinkage is expected by retailers. They know it will happen, and they price goods accordingly. They install self-check-outs for example, knowing that the wage savings are worth the higher rate of theft. The rest of us pay a bit more to compensate the retailer for people who steal.

In a business with low margins, theft can be a real problem. If a retailer buys something for $1 and plans to sell it for $1.10, but a shoplifter pockets it, the shop loses $1. The company has to sell 10 products to paying customers to make back that dollar. The store can expect that and price things accordingly, and still lose money if theft increases.

And theft seems to be increasing. Which is not surprising as prices go up. The tighter household budgets get, the more people will steal. And the more people feel like supermarkets are screwing them, the less they see theft as wrong.

In a recent Reddit thread on shoplifting, several users expressed the sentiment that theft from supermarkets could be justified.

“[T]hey harm our country more than any individual that steals from them. It isn’t right to steal, but it is levelling the playing field ,” wrote one user.

But as the head of the Australian Retail Association (ARA) points out, it’s not just hungry people doing the stealing.

“Typically, electronics, fashion, personal accessory and grocery retailers bear the brunt of shoplifting,” said ARA CEO Paul Zahra

“Organised crime – where two or more individuals work together to steal and typically on-sell the goods – is a significant proportion of shrinkage in 2023. These criminals tend to target higher value items – from hardware to jewellery, computers and other technology items. Unfortunately, violence is often associated with these crimes.”

Across the world we are in a shoplifting epidemic. America has it worst. But Australia is affected too.

Kmart’s owner Wesfarmers has said that it is being affected by increased “shrinkage”, citing it as an example of “cost of doing business pressure.”

Coles is also seeing higher rates of what it calls “loss”, and the new CEO is blaming theft for a reported 20 per cent increase in stock loss.

Most shoplifting offences don’t involve police, but official statistics are certainly showing a big uptick in theft from retailers, after a lull during the pandemic. The next chart shows statistics from NSW, but the rest of the country shows a similar pattern.

Most of us wouldn’t steal from an individual. But stealing from a big organisation is seen as less evil because the cost is spread over many people, rather than just a few. The pain is shared between other customers who pay higher prices, and shareholders who receive lower profits. Does that make it better?

Despite lower margins, Myer still made profit in the first half of the year. Profit after tax was $65 million, up from $32 million in the equivalent period the year before. If people are stealing bread for their kids, I’m willing to look the other way. But if they’re stealing luxury handbags, less so.

Jason Murphy is an economist | @jasemurphy. He is the author of the book Incentivology.