Gap closes final Australian store ending its disastrous foray Down Under

THE last Aussie store of a US giant has quietly closed. A lesson in how not to do retail, with some calling it a “retail living-corpse”.

IN THE Westfield shopping centre in Sydney’s CBD there’s a gap where a shop should be. The windows are boarded up, the fixtures and fittings are gone, no customers will darken its doors again.

This is where the flagship Australian branch of Gap, until days ago, proudly stood. It was the shiny all-singing, all-dancing beachhead for the iconic US retailer. But it was a voyage Down Under that ended in disaster this month.

Embattled luxury goods retailer Oroton, which was saved from the brink of collapse in December, announced it was bringing Gap to Australia in 2013 with plans to open up to 15 stores stocked floor to ceiling with stone-washed jeans, pastel coloured T-shirts and hoodies emblazoned with its own name.

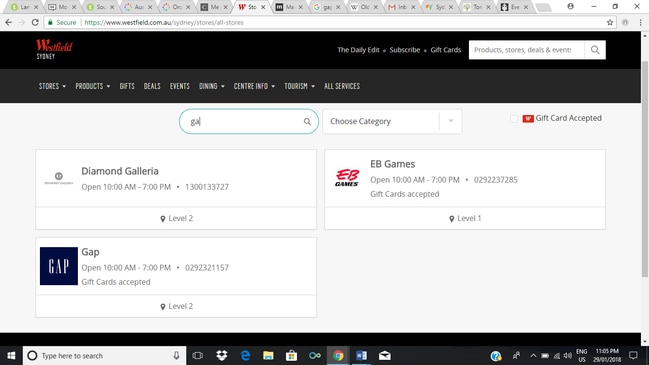

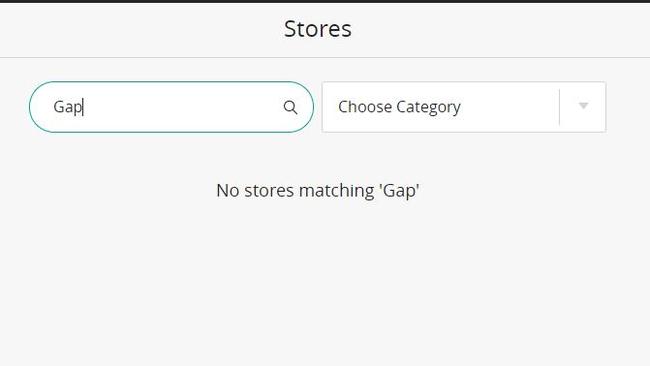

As late as Sunday, Gap was listed as open on the Westfield Sydney website. By Monday, all mention had been scrubbed. “No stores matching ‘Gap’” the website now states.

In the sad final days of Gap’s Australian adventure, the stores were a shadow of their former selves. Clothes, many 70 per cent or more off, were piled high on racks. And if you had need of a rack, well they were for sale too.

RETAIL LIVING CORPSE

The brand may have been well known but, in hindsight, said Pippa Kulmar of retail consultancy Retail Oasis, it’s questionable whether Gap should ever have entered Australia.

“There was a heyday when Gap was brilliant but that was pre-H&M and Zara,” she told news.com.au. “They had that cool factor in the 1990s alongside Abercrombie & Fitch and Benetton, brands that have also failed to reinvent themselves.”

Nonetheless, she could see the temptation to bring a big name to Australia.

“Part of the decision was that mass awareness. But as much as it’s about marketing, it’s about product. People can be drawn into a store but if they don’t want to buy anything it’s a theoretical exercise.”

Others have been less kind. In 2015, just as Gap was opening stores in Australia, it was shutting 175 in the US. Lisa Armstrong, head of fashion at the UK’s Telegraph newspaper, said she was circumspect of the turnaround plan.

“To many observers, this looks less like a rescue strategy than the latest miserable convulsion of a wretched retail living-corpse,” she wrote.

From the mid-2000s on, Gap had lost its way creatively, was expensive in the face of fast fashion rivals and failed to excite a new generation of shoppers, she said.

“Gap was where your parents had shopped, a factor bound to deter most self-respecting offspring from ever entering its stores.”

In the same year, Oroton said the Gap stores in Australia had seen sales drop by 0.9 per cent.

OUT-GAPPED GAP

On the thronged Pitt Street Mall in Sydney, at the entrance to the Westfield centre, the distinctive blue Gap logo has been removed from the side of the building. An unweathered perfect square is all that remains.

Opposite is a vast and busy Uniqlo store. The Japanese retailer, full of jeans and plain T-shirts, has seemingly out-Gapped Gap.

“I think Uniqlo have captured the basics market but their business is underpinned by a smart back end where they work directly with raw material suppliers so they get really good prices,” said Ms Kulmar.

Price was one of the problem areas for Gap.

“Fashion is a tough place to play. There’s a real polarisation of fashion splitting the market so you might see someone with Zara jeans and Gucci bag,” she said.

“It’s moved to high and low and Gap were stuck in the middle not offering creative direction from the catwalk or great value like H&M and Zara.”

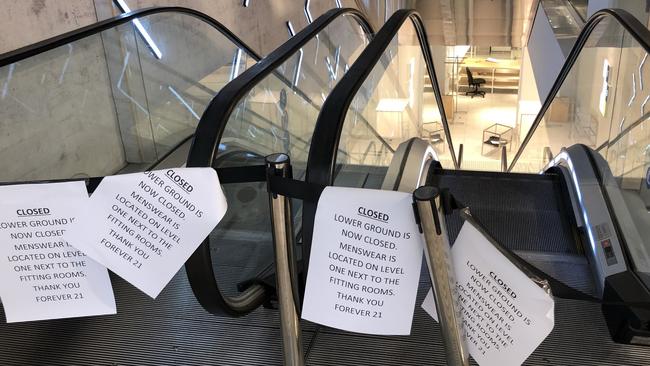

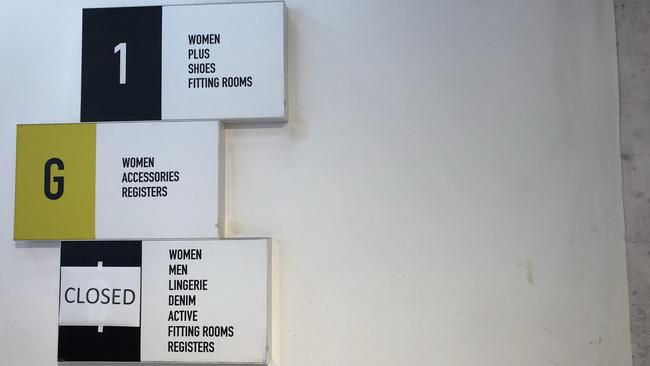

Certainly, Gap isn’t the only international name that has been mauled in Australia. Topshop is clinging on with three stores while it seems where Gap has gone, Forever 21’s Sydney store will soon follow.

A third of the store is sealed off and Woolworths is looking to move in when the final sun dress and pair of shades are finally sold.

Globally, even behemoth H&M is struggling with the Swedish firm having announced a surprise 4 per cent sales drop in December.

Chief executive Karl-Johan Persson said fewer people were coming into H&M’s physical stores and they would be shuttering some as a result. They needed to beef-up their online offer — an area where Gap also lagged.

The Australian fashion market isn’t growing and online retailers like ASOS and The Iconic are snaffling sales from established names.

OLD NAVY

In the 13 weeks to October 2017, overall global sales from Gap branded stores saw a 1 per cent rise; modest it may be but the company is celebrating it as a positive sign. However, a brighter spot for Gap has been its Old Navy branded stores. A less expensive offering, Old Navy still maintains a fashionable edge and saw sales rise 4 per cent.

Oroton also held the Australian rights to Old Navy. Did it bring the wrong Gap-owned brand to Australia? It would have been an even bigger risk to open Old Navy stores rather than Gap, said Ms Kulmar, as the former was not a known name. But there was one retailer, in a similar vein, which she said could work.

“I actually think (Irish founded, UK-owned fashion store) Primark would have resonance here. Australians love London, they know what’s going on in the UK and Primark would make sense.”

But it’s qualified enthusiasm. While cosmetics and streetwear shoes are causing excitement, pure play fashion is struggling and top heavy with competitors.

“If I were looking at entering the Australian market, I wouldn’t be looking at fashion unless you have a great creative direction and a technological advantage in how quick you can get supply from the factory to the store,” she said.

“Unless you’re super, super smart it’s just really hard to compete.”

The former Gap stores, languishing empty in shopping centres in Sydney and Melbourne, and 200 staff without jobs, are testament just how tough retail has become.