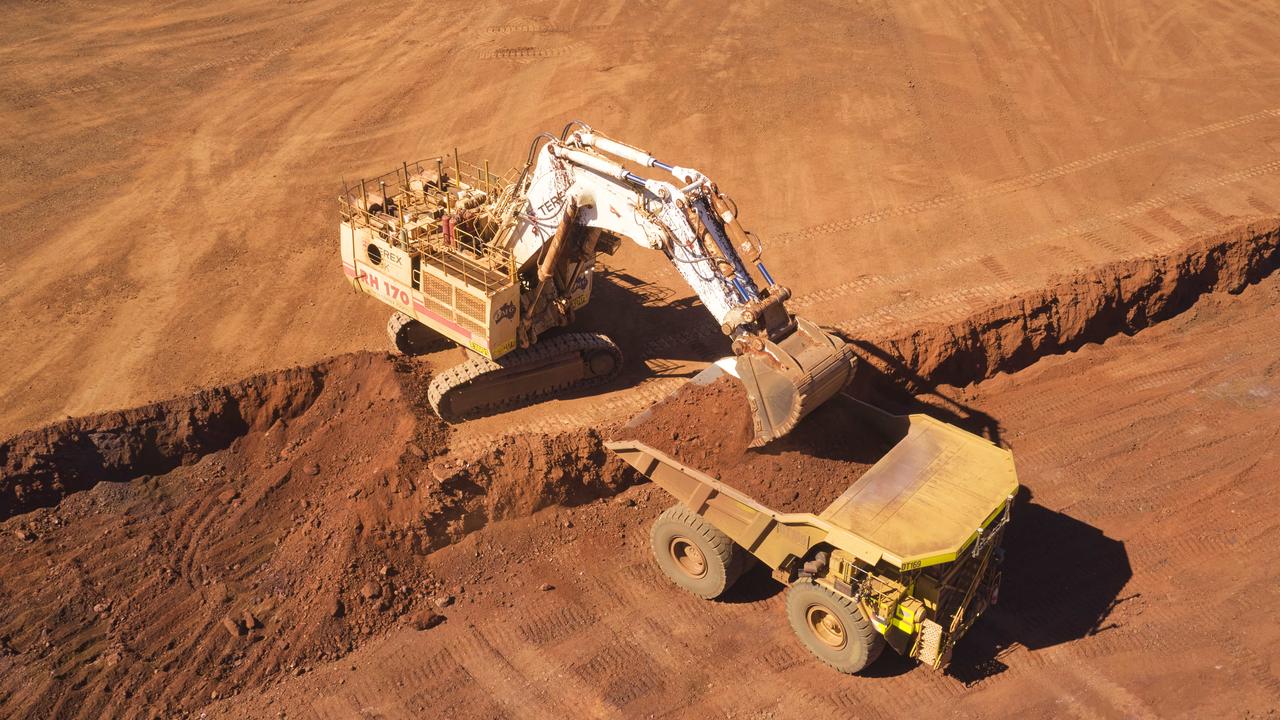

Two investments soar as Australian market goes haywire

Australia’s number one export may be on its knees but there are two investments that are skyrocketing – although everything still remains uncertain.

Nickel’s prospects have nosedived. Iron Ore is floundering. But copper and gold are racing ahead amid a world of change and uncertainty.

BHP has announced it has paused construction work on its new Kalgoorlie nickel smelter after laying off a quarter of its West Musgrave mining operation workforce. It blames a flood of cheap nickel supplies on the market after new coal-fired, Chinese-operated facilities came online in Indonesia last year.

China’s construction industry crisis, meanwhile, shows no sign of easing. Smelters and mills are going into hibernation across the country, with analysts predicting Australia’s number one export iron ore may sink below $US90 a tonne by the end of the year.

But two other metals have some shine amid generally low trading volumes.

Copper’s future was uncertain earlier this month as Chinese producers moved to collaborate on a production cut. A glut in supply had dramatically cut their margins.

In the past week, however, it’s begun to test the $US9000 a tonne mark. The market has recorded something of a bounce-back, with analysts saying the long-term outlook for the critical mineral looks very strong, with nations worldwide moving to electrify every level of their economies.

It’s currently trading at around $US8800.

And amid it all, gold set a new $US2200 price record Thursday after the US Federal Reserve announced it planned three interest rate cuts this year, despite ongoing inflation concerns.

Like copper, analysts argue the record price – the fifth recorded this month – reflects a shift towards long-term thinking among investors.

Central banks are buying up the precious metal as global tensions soar. And gold’s reputation as a “safe haven” in troubled times is reflecting Ukraine’s setbacks in defending itself from Russia’s invasion, the brutal Israel-Hamas war threatening to spill across borders, the sustained attacks on shipping in the Red Sea by Houthi rebels, China’s aggressive push into Japanese and Philippines waters, and the prospect of a return to the US Presidency of Donald Trump after the November elections.

Supply-demand seesaw

With global manufacturers, refiners and producers having run down their metals stocks during and after the Covid-19 pandemic, prices have become far more sensitive to short-term fluctuations in supply and demand.

Without stockpiles as a buffer, every bit of news can seem extreme. For example, an unexpected mine closure due to extreme weather could lead to shortages.

But it’s a different story for iron ore. The bulk metal has been piling up in Chinese ports (140.9 million tonnes). And storing that much material comes with a significant cost.

And while movements in both iron ore and copper prices have been positive over the past week, analysts point to the underlying disparities influencing their future. These are more evident in their monthly price movements – up around 10 per cent for copper and down some 20 per cent for iron ore.

That’s because underlying demand is different.

But differences in scale also mean copper and iron are not in the same league when it comes to Canberra’s account sheet. Iron ore worth $A124 billion was exported last financial year. Copper earned the country $A12.3 billion over the same period.

Meanwhile, Beijing is yet to move to pump significant stimulus into its stalled construction industry. Instead, it is showing signs of shifting its emphasis away from an investment-based economy towards one focused on consumers.

That could spell an end to the decades-long explosion in demand for structural steel. And more than half of that steel was made from Australian iron ore.

Analysts say China’s property bubble – which has left families with nothing to show for their large deposits – is having another unanticipated effect. They’re shifting their money into gold.

Coins. Bars. Jewellery. Just as with the world’s central banks, China’s citizenry is seeking somewhere to park their money while they wait for their national economy – and global markets – to settle down.

Copper comeback?

Unlike iron, copper has a growing role at the core of a push to restructure global economies.

And instead of coming off record-high prices, it’s been through a relatively subdued period.

It’s not seen the kind of growth recorded by metals and minerals necessary for advanced battery construction – and therefore in demand for the new electric vehicles market.

But it is central in constructing extensive new power cable grids linking new sustainable energy producers – such as wind and solar farms and hydro-electric plants – to heavy industries transitioning their technologies away from coal and gas.

Now analysts say China’s proposed production cuts have caused investors to foresee a tightening of supply – and the implications that will bring.

In the past week, Citi and Goldman Sachs have projected copper prices to rise to $US10,000 a tonne by the end of the year. They expect it to move on to $US12,000 in 2025.

But even this is uncertain. China still holds significant copper stock – the same backlog that caused Beijing to summon producers to talks earlier this month. And its proposed production cuts have yet to emerge.

It’s a different story for global stockpiles, however. The London Metals Exchange says its copper inventories have almost halved since the end of last year.

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel